Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Revista da Associacao Paulista de Cirurgioes Dentistas

versão impressa ISSN 0004-5276

Rev. Assoc. Paul. Cir. Dent. vol.70 no.4 Sao Paulo Out./Dez. 2016

International Association for Dental Traumatology (IADT)

Traumatic Dental Injuries: Adherence to Treatment Guidelines Critical to Positive Patient Outcomes

By Dr. Nestor Cohenca, DDS, FIADT

Dental trauma occurs daily. When protocols are not followed, healthy teeth are lost and the patient's quality of life compromised. In addition, beyond the patient's health, first responders may be subject to legal action when protocols are no followed and victims or their insurance companies sue for damages.

A typical example would be when a student-athlete is injured during a high school basketball game, resulting in the loss of a tooth. The team's trainer/coach takes the injured player to the ER, along with the tooth, which the trainer placed in a cup or dry gauze and gives to the emergency personnel. Unfortunately, since proper protocol was not followed, the patient will ultimately lose this tooth. Treatment, if even possible will be often complex, time consuming and expensive requiring multidisciplinary approaches. Depending on the age of the patient the tooth will need to eventually be extracted and replaced.

Loss of front tooth as result of an accident is legally defined as a 1-3% disability. Thus, intervention of lawyers and insurance companies is almost always a given. Patient and/or parents will demand a compensation for all the physical and psychological damages. If guidelines are not followed, the legal review will lead to a significant professional liability with all its consequences.

The International Association first developed guidelines establishing protocols for treatment of traumatic dental injuries for Dental Traumatology (IADT) in 1991. Guidelines are reviewed periodically based on new research or evidence, with updates released typically every two to four years. While the American Association of Endodontics (AAE) and American Association of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) established their own set of guidelines, today all three organizations are using the same guidelines, based on the original IADT recommendations. And, effective January 2017, guidelines will begin to be reviewed quarterly; meaning new guidelines may be released more frequently.

Dental trauma guidelines provide specific recommendations and protocols to ensure the best positive patient outcomes. However, trauma guidelines have not been consistently followed, as most professionals are unaware of their existence or even worst, decide to ignore them. Dental trauma professionals, IADT, AAE and AAPD all have been working to increase the knowledge of not only the guidelines, but equally important the prevention of such injuries. The importance of treatment guidelines is to provide guidance on what to expect, what the expected outcomes are based on the injury, the different factors related to that injury, along with a clear recommendation about the immediate treatment specifically to the type of injury. It's critically important to understand that the immediate care performed by the first responder will determine if the tooth will be saved or not. Simple as that! Since non-dental professionals, such as teachers, coaches, trainers, emergency medical technicians, etc. are the ones where injuries happen their education on the proper immediate treatment will define not only the dental outcome but the psychological, aesthetic, social well-being and quality o life of the child.

In the past, education and training of non-dental professionals (commonly present at site of injuries) was not readily accessible. Unfortunately colleges and universities do not provide enough education on dental trauma. Yet today, access to guidelines and education is simple. The IADT, AAE and AAPD provide free access through their respective web sites. Additionally, webinars and online courses are also available, meaning professionals, providers, patients, and attorneys all have access to these guidelines. What this means for first-responders, whether a high school coach or EMT treating an accident victim, is that ignorance about guidelines will no longer be acceptable.

Trauma guidelines and litigation

In addition to providing a treatment roadmap, trauma guidelines also are used as a legal document by attorneys and insurance companies regarding proper course of action in the case of trauma. While guidelines are a recommendation, if someone treats a case and does not follow recommended protocols, they can be liable and at risk for a lawsuit for not following published trauma guidelines.

In cases where litigation enters the scene, it's important that proper treatment guidelines are followed. The insurance company representing an accident victim or attorneys representing the victim in a bar fight will seek damages associated with the treatment of injuries. Attorneys or insurance companies typically do not go after dentists, but may seek compensation from the place or person responsible for the accident. For example, consider first responders treating an auto accident victim or a physical education (PE) teacher treating a student, each of who have suffered a traumatic dental injury. Legal teams and insurance companies will request all the documentation on the case to evaluate the immediate treatment at place of injury, at the ER, and dental practice. After all, there entire job is to protect their clients and compensate them for the physical and psychological damages for the rest of patient's life! All factors are taken into account when you have insurance or legal implication. This also applies to dentists, whether or not litigation is against the dentist. They will seek notes, chart notes, x-rays, treatment plan, and the cost associated with the immediate and long-term life of the patient.

Get informed: What first responders can do

The challenge for dental professionals is that they are not first on the scene to provide treatment and rely on first responders to follow guidelines to ensure the best chance for a positive patient outcome. The best course of action for dental providers is to educate first responders about the existence of guidelines to ensure patient health and to protect against costly litigation. Traumatic injuries occur approximately in 30% of the population. Just to put things in perspective, in USA 169 people are exposed to facial/dental injuries every single day. As such, awareness needs to extend beyond the dental community to first care responders. We totally depend on them!

The first step toward improving treatment is awareness. Encourage your network to do research and to seek out information. There are courses and webinars available as a source of information to not only the dental community, but for coaches, teachers, and others who may be considered first responders.

The next step is to go to communities – schools, hospitals and other organizations to talk with people that are at the site of injury and try to promote the knowledge among these groups. Encourage your community to visit the web sites and social media channels of IADT, AAE, and AAPD for information and updates.

Bottom line: Outcome of traumatic injuries often depends exclusively on the immediate care provided at site of injury. Therefore, encourage first responders to take initiative, learn about how to prevent treat traumatic dental injuries, as there are plenty of resources available. For more information, visit www.iadt-dentaltrauma.org.

About the author:

Nestor Cohenca is an endodontist and a leading expert in dental trauma and pediatric endodontics. He is in private practice at Lakeside Endodontics, Everett, Wash. Also, he is an affiliate professor with the Department of Pediatric Dentistry at the University of Washington School of Dentistry and with Seattle Children's Hospital. Dr. Cohenca is the upcoming President of the IADT and provides online coursework for dental and non-dental professionals seeking CE hours – visit http://oralsurgeryservices.com/online/ dental-trauma/ for details.

Diretrizes da Associação Internacional de Traumatologia Dentária para a abordagem de lesões dentárias traumáticas: 1. Fraturas e luxações de dentes permanentes

Tradutores:

Emmanuel João Nogueira Leal da Silva

Raquel Assed Bezerra da Silva

Paulo Nelson Filho

Original:

International Association of Dental Traumatology guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries: 1. Fractures and luxations of permanent teeth. Diangelis AJ, Andreasen JO, Ebeleseder KA, Kenny DJ, Trope M, Sigurdsson A, Andersson L, Bourguignon C, Flores MT, Hicks ML, Lenzi AR, Malmgren B, Moule AJ, Pohl Y, Tsukiboshi M; International Association of Dental Traumatology. Dent Traumatol. 2012 Feb;28(1):2-12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2011.01103.x.o

RESUMO

Lesões dentárias traumáticas (LDTs) de dentes permanentes ocorrem com frequência em crianças e adultos jovens. Fraturas coronárias e luxações são as LDTs mais comuns. O diagnóstico, plano de tratamento e acompanhamento apropriados são fatores importantes para garantir um prognóstico favorável. Diretrizes devem auxiliar cirurgiões-dentistas e pacientes no processo de tomada de decisão e proporcionar um atendimento eficiente e eficaz. A Associação Internacional de Traumatologia Dentária (International Association of Dental Traumatology - IADT) desenvolveu um documento consensual, após revisão da literatura odontológica e discussões em grupo. Pesquisadores experientes e clínicos de diversas especialidades foram incluídos no grupo de discussão. Nos casos onde os dados foram inconclusivos, as recomendações foram baseadas em opinião consensual dos membros do conselho da IADT. Estas diretrizes representam as melhores evidências atuais, com base em pesquisa bibliográfica e opinião profissional. O principal objetivo destas diretrizes é delinear uma abordagem para o atendimento imediato ou de urgência das LDTs. Neste primeiro artigo serão apresentadas as diretrizes da IADT para a abordagem de fraturas e luxações de dentes permanentes.

Descritores: consenso; fratura; luxação; revisão; trauma; dente.

Lesões dentárias traumáticas (LDTs) ocorrem com grande frequência em crianças de idade pré-escolar, escolar e em adultos jovens e correspondem a 5% de todas as lesões pelas quais as pessoas procuram tratamento.1,2 Uma revisão de literatura de 12 anos relata que 25% de todas as crianças em idade escolar sofreram algum tipo de trauma dentário e que 33% dos adultos sofreram traumatismos na dentição permanente, sendo que a maioria dessas lesões ocorreu antes dos 19 anos.3 As luxações são as LDTs mais comuns na dentição decídua, enquanto as fraturas coronárias são mais comumente relatadas na dentição permanente.1,4,5 LDTs representam um desafio para clínicos no mundo todo. Consequentemente, diagnóstico, plano de tratamento e acompanhamento adequados são fundamentais para assegurar um prognóstico favorável.

As diretrizes devem auxiliar os Cirurgiões-Dentistas, outros profissionais de saúde e pacientes no processo de tomada de decisão. Além disso, devem ter credibilidade, serem práticas e de fácil compreensão, com o objetivo de proporcionar um atendimento o mais eficiente e eficaz possível.

As presentes diretrizes da Associação Internacional de Traumatologia Dentária (International Association of Dental Traumatology - IADT) representam um conjunto atualizado de orientações, com base nas diretrizes originais publicadas em 2007.6-8 A atualização foi realizada a partir de uma revisão da literatura atual utilizando as bases de dados EMBASE, MEDLINE e PUBMED com buscas entre os períodos de 1996-2011, bem como pesquisa ao conteúdo da revista Dental Traumatology dos períodos de 2000-2011. As palavras-chave utilizadas incluíram fraturas dentárias, fraturas radiculares, luxação dentária, luxação lateral e dentes permanentes, dentes permanentes intruídos e dentes permanentes luxados (tooth fractures, root fractures, tooth luxation, lateral luxation and permanent teeth, intruded permanente teeth, and luxated permanent teeth).

O principal objetivo dessas diretrizes é delinear uma abordagem para o atendimento imediato ou de urgência das LDTs. Entende-se que o tratamento subsequente das LDTs pode requerer intervenções secundárias e terciárias envolvendo consultas especializadas, serviços, e/ou materiais/ métodos nem sempre disponíveis durante o atendimento primário.

A IADT publicou o seu primeiro conjunto de diretrizes no ano de 2001 e atualizou-as em 2007.6-13 Assim, como nas diretrizes anteriores, o grupo de trabalho foi composto por pesquisadores e clínicos experientes de diversas especialidades odontológicas, bem como clínicos gerais. As presentes diretrizes representam as melhores evidências atuais disponíveis, com base em pesquisa bibliográfica e parecer profissional. Nos casos onde os dados obtidos na revisão não foram conclusivos, as recomendações foram baseadas na opinião consensual do grupo de trabalho, seguida por revisão realizada pelos membros do conselho de diretores da IADT. Compreende-se que as diretrizes de tratamento devem ser aplicadas com base na avaliação das circunstâncias clínicas específicas, no julgamento do profissional e nas características individuais dos pacientes, incluindo, mas não limitando, a aderência ao tratamento, custos envolvidos e o entendimento do prognóstico imediato e em longo prazo de tratamentos alternativos versus o não-tratamento. A IADT não pode e não garante resultados favoráveis a partir da adesão estrita às presentes diretrizes, mas acredita que a sua aplicação pode maximizar as chances de um prognóstico favorável.

As presentes diretrizes serão divididas em três partes:

Parte I: Fraturas e luxações de dentes permanentes

Parte II: Avulsão de dentes permanentes

Parte III: Lesões na dentição decídua

Embora as diretrizes ofereçam recomendações para o diagnóstico e tratamento de LDTs específicas, não fornecem uma informação abrangente pormenorizada, como a encontrada em livros didáticos, na literatura científica e, mais recentemente, no Guia de Trauma Dental (Dental Trauma Guide – DTG) que pode ser acessado em http:// www.dentraltraumaguide.org. Além disso, o DTG, também disponível na web-page da IADT (http://www.iadt-dentaltrauma.org), proporciona uma documentação visual e animada dos tratamentos, assim como estimativas de prognóstico para as diferentes LDTs.

Recomendações/Considerações gerais

Exame clínico

Uma descrição detalhada dos protocolos, métodos e documentação para a avaliação clínica das LDTs pode ser encontrada em livros didáticos atuais.1,14,15

Exame radiográfico

Várias projeções e angulações são rotineiramente recomendadas, porém o clínico deve decidir quais radiografias são necessárias para cada caso. As seguintes radiografias são recomendadas:

• Uma radiografia periapical com o centro do feixe de raios-X incidindo com angulação horizontal perpendicular ao dente em questão.

• Uma radiografia oclusal.

• Radiografias periapicais com diferentes angulações laterais, distalizada ou mesializada com relação ao dente em questão.

Modalidades de imagem emergentes, como a tomografia computadorizada de feixe cônico (TCFC) fornecem melhor visualização das LDTs, particularmente nos casos de fraturas radiculares e luxações laterais, permitindo um monitoramento pós-operatório e possíveis complicações. A disponibilidade desse recurso é limitada, e a sua utilização não é considerada rotina; no entanto, informações específicas são disponíveis na literatura científica.16,17

Tipo e duração da contenção

Evidências atuais suportam a utilização de contenção não-rígida e de curta duração para dentes luxados, avulsionados e com raízes fraturadas. Embora nem o tipo nem a duração da contenção de dentes luxados e dentes com raízes fraturadas estejam significantemente relacionadas ao prognóstico, a contenção é considerada a melhor forma de se manter o dente reposicionado corretamente, proporcionando conforto ao paciente e melhoria da função.18,19

Uso de antibióticos

Existem limitadas evidências para a utilização de antibióticoterapia sistêmica nos casos de lesões de luxação e nenhuma evidência de que a cobertura antibiótica melhore o prognóstico de dentes fraturados. A utilização de antibióticos permanece a critério do clínico, uma vez que as LDTs são frequentemente acompanhadas por lesões de tecidos moles e associadas com outros tipos de lesão, que podem exigir intervenções cirúrgicas. Além disso, o estado de saúde do paciente pode justificar a cobertura antibiótica.19,20

Testes de sensibilidade

Testes de sensibilidade referem-se a testes (frio e/ou elétrico) que têm por objetivo determinar a condição da polpa dental. No momento do acidente, os testes de sensibilidade frequentemente não geram nenhuma resposta, indicando uma ausência transitória de resposta pulpar. Consequentemente, pelo menos dois sinais e sintomas são necessários para realizar o diagnóstico de necrose pulpar. Consultas pós-operatórias regulares são necessárias para realizar o diagnóstico da condição do tecido pulpar.

Dentes permanentes com rizogênese incompleta versus dentes permanentes com rizogênese completa

Todo esforço deve ser realizado para preservar a vitalidade pulpar em um dente permanente com rizogênese incompleta, para garantir a continuidade do desenvolvimento radicular. A grande maioria das LDTs ocorre em crianças e adolescentes, onde a perda de um elemento dentário possui sérias consequências para a vida. Dentes permanentes com rizogênese incompleta apresentam uma considerável capacidade de reparo após exposições pulpares traumáticas, lesões de luxação e fraturas radiculares. Exposições pulpares secundárias às LDTs respondem bem a terapias pulpares conservadoras que mantêm a vitalidade pulpar e permitem a continuidade de formação radicular.21-24 Além disso, terapias emergentes demonstraram a capacidade de revascularizar/regenerar tecido vital nos canais radiculares de dentes permanentes com rizogênese incompleta e necrose pulpar.25-30 Dentes traumatizados frequentemente apresentam uma combinação de diferentes lesões. Estudos têm demonstrado que dentes com fratura coronária com ou sem exposição pulpar associados à luxação apresentam uma maior frequência de necrose pulpar.31 Os dentes permanentes com rizogênese completa que sofrem LDTs severas são susceptíveis à necrose pulpar, sendo nesses casos recomendada a realização de pulpectomia preventiva uma vez que o desenvolvimento radicular já foi concluído.

Obliteração do canal radicular

A obliteração do canal radicular (OCR) ocorre mais frequentemente em dentes com ápices abertos que tenham sofrido uma grave lesão de luxação. Essa condição geralmente indica uma polpa com vitalidade. Extrusão, intrusão e lesões de luxação lateral têm altas taxas de OCR.32,33 As subluxações e fraturas coronárias também podem apresentam OCR, embora com menor frequência.34 Além disso, OCR é uma ocorrência comum após fratura radicular.35,36

Instruções aos pacientes

A adesão do paciente às visitas de acompanhamento e os cuidados domiciliares contribuem para um melhor prognóstico, após uma LDT. Os pacientes e pais de pacientes jovens devem ser aconselhados a respeito dos cuidados com o(s) dente (s) traumatizado(s) para um melhor reparo e prevenção de traumas futuros, ao evitar a participação em esportes de contato, ao realizar meticulosa higiene bucal e efetuar bochecho com agente antibacteriano, como o gluconato de clorexidina a 0.1% livre de álcool, por 1-2 semanas.

Recursos adicionais

Além das recomendações gerais mencionadas anteriormente, os clínicos devem ser incentivados a acessar o DTG, a revista Dental Traumatology e outras revistas em busca de informações referentes a possíveis atrasos na instituição do tratamento37, luxações intrusivas38-47, fraturas radiculares48-52, tratamentos pulpares de dentes fraturados e luxados34,53-64, contenção18,39,65-68 e antibióticos69.

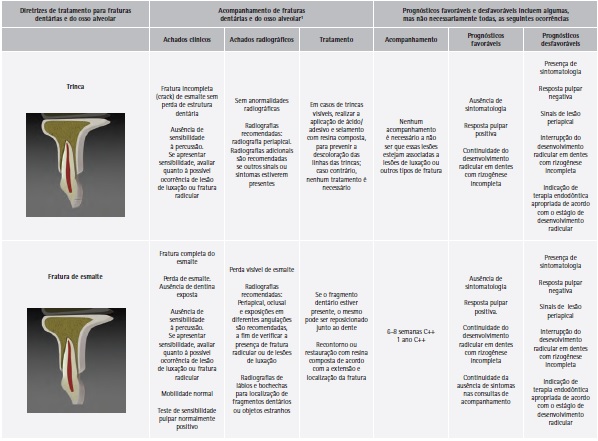

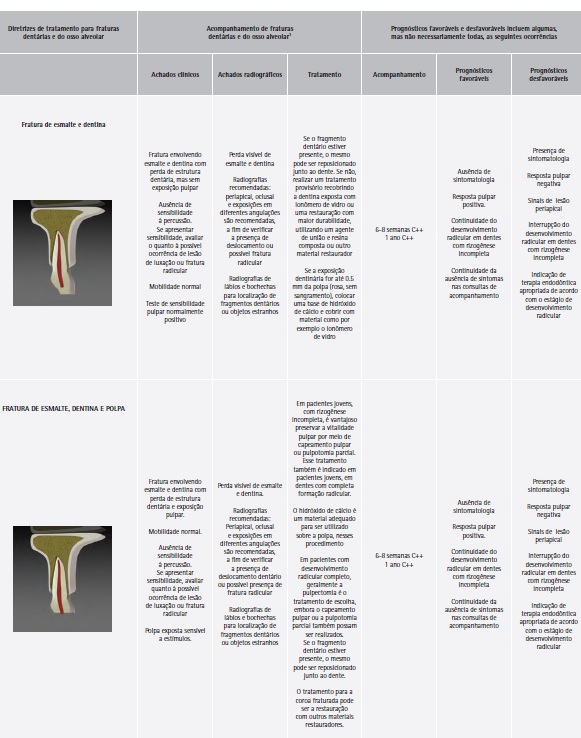

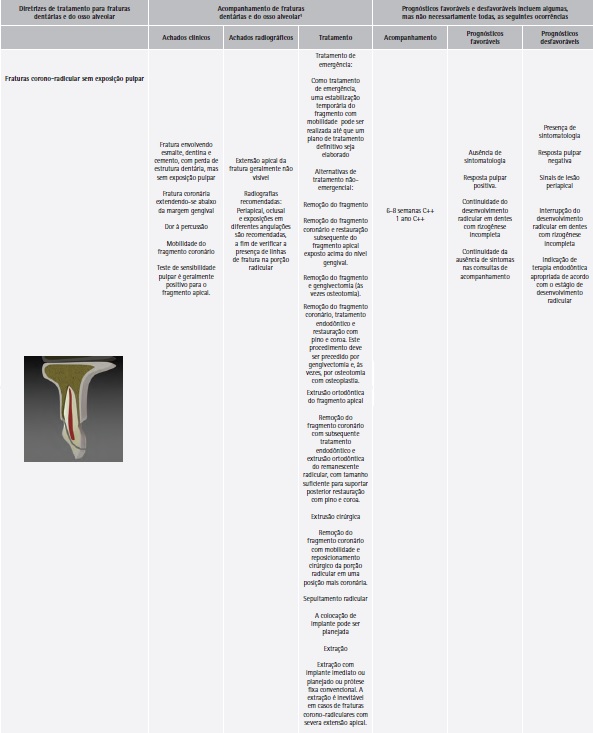

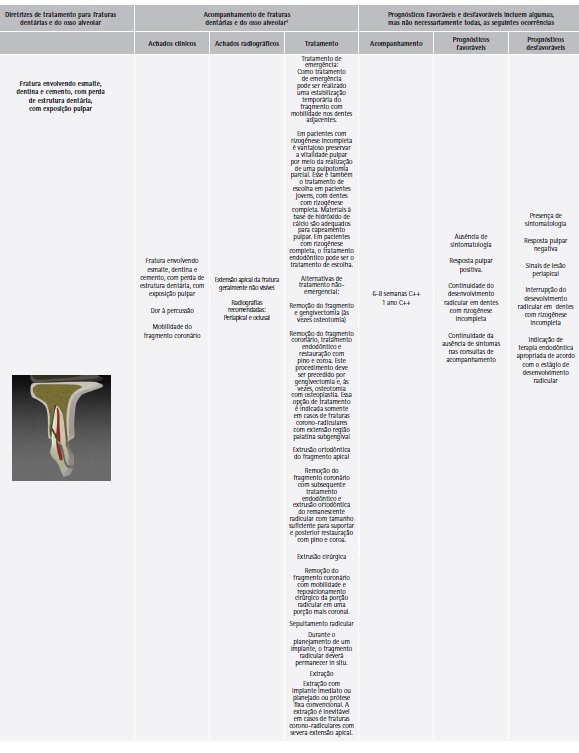

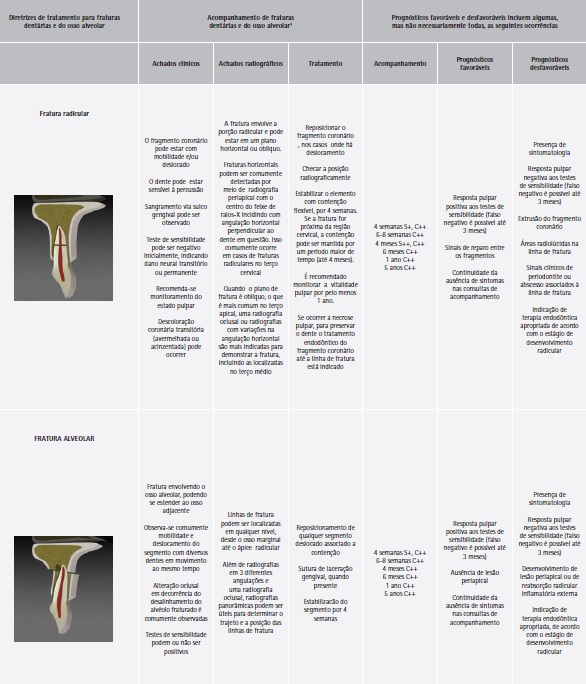

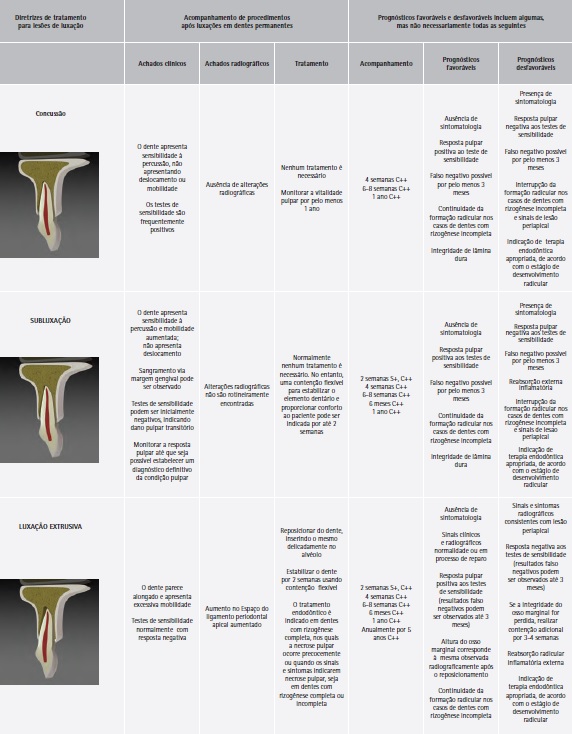

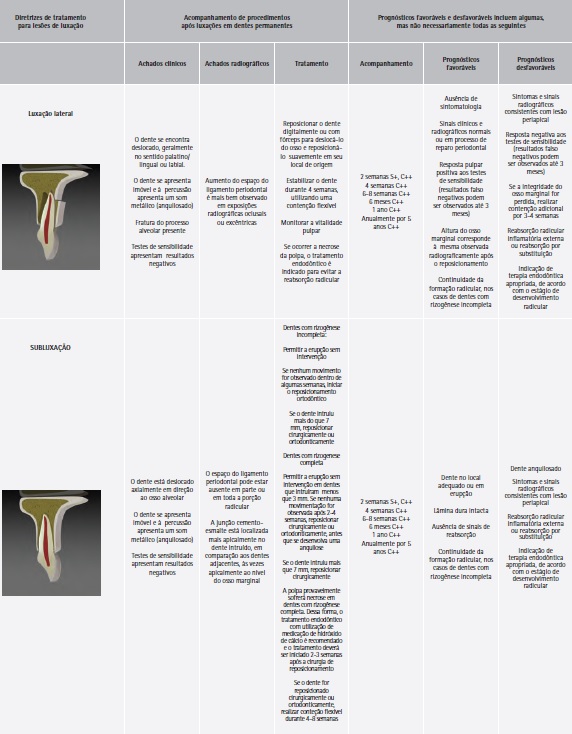

C++, exames clínicos e radiográficos; S+ remoção da contenção; S++ remoção da contenção em fraturas do terço cervical.

1 Para dentes com fraturas coronárias com lesão por luxação concomitante, utilizar o cronograma de acompanhamento de dentes luxados.

2 Sempre que existir a evidência de reabsorção inflamatória externa, o tratamento endodôntico deve ser iniciado imediatamente, com a utilização de hidróxido de cálcio como medicação intracanal.

AGRADECIMENTOS

Este artigo é uma tradução autorizada do trabalho original:

Diangelis AJ, Andreasen JO, Ebeleseder KA, Kenny DJ, Trope M, Sigurdsson A, Andersson L, Bourguignon C, Flores MT, Hicks ML, Lenzi AR, Malmgren B, Moule AJ, Pohl Y, Tsukiboshi M; International Association of Dental Traumatology. International Association of Dental Traumatology guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries: 1. Fractures and luxations of permanent teeth. Dental Traumatology 2012;28(1):2- 12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2011.01103.x. Publisher: Wiley.

REFERÊNCIAS

1. Andreasen JO, Andreasen FM, Andersson L. Textbook and color atlas of traumatic injuries to the teeth, 4th edn. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2007.

2. Petersson EE, Andersson L, Sorensen S. Traumatic oral vs nonoral injuries. Swed Dent J 1997;21:55–68.

3. Glendor U. Epidemiology of traumatic dental injuries – a 12 year review of the literature. Dent Traumatol 2008;24:603–11.

4. Flores MT. Traumatic injuries in the primary dentition. Dent Traumatol 2002;18:287–98.

5. Kramer PF, Zembruski C, Ferreira SH, Feldens CA. Traumatic dental injuries in Brazilian preschool children. Dent Traumatol 2003;19:299–303.

6. Flores MT, Andersson L, Andreasen JO, Bakland LK, Malmgren B, Barnett F et al. Guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries. 1. Fractures and luxations of permanent teeth. Dent Traumatol 2007;23:66–71.

7. Flores MT, Andersson L, Andreasen JO, Bakland LK, Malmgren B, Barnett F et al. Guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries. 11. Avulsion of permanent teeth. Dent Traumatol 2007;23:130–6.

8. Flores MT, Malmgren B, Andersson L, Andreasen JO, Bakland LK, Barnett F et al. Guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries. 111. Primary Teeth. Dent Traumatol 2007;23:196–202.

9. Flores MT, Andreasen JO, Bakland LK, Feiglin B, Gutmann JL, Oikarinen K et al. Guidelines for the evaluation and management of traumatic dental injuries (part l of the series). Dent Traumatol 2001;17:1–4.

10. Flores MT, Andreasen JO, Bakland LK, Feiglin B, Gutmann JL, Oikarinen K et al. Guidelines for the evaluation and management of traumatic dental injuries (part 2 of the series). Dent Traumatol 2001;17:49–52.

11. Flores MT, Andreasen JO, Bakland LK, Feiglin B, Gutmann JL, Oikarinen K et al. Guidelines for the evaluation and management of traumatic dental injuries (part 3 of the series). Dent Traumatol 2001;17:97–102.

12. Flores MT, Andreasen JO, Bakland LK, Feiglin B, Gutmann JL, Oikarinen K et al. Guidelines for the evaluation and management of traumatic dental injuries (part 4 of the series). Dent Traumatol 2001;17:145–8.

13. Flores MT, Andreasen JO, Bakland LK, Feiglin B, Gutmann JL, Oikarinen K et al. Guidelines for the evaluation and management of traumatic dental injuries (part 5 of the series). Dent Traumatol 2001;17:193–8.

14. Andreasen JO, Bakland LK, Flores MT, Andreasen FM. Traumatic dental injuries: a manual, 3rd edn. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011.

15. Pinkham JR, Casamassino PS, Fields HW Jr, McTigue DJ, Mowak A editors. Pediatric dentistry, 4th edn. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2005.

16. Cohenca M, Simon JH, Roges R, Morag Y, Malfax JM. Clinical Indications for digital imaging in dento-alveolar trauma. Part I: traumatic injuries. Dent Traumatol 2007;23:95–104.

17. Cohenca N, Simon JH, Mathur A, Malfax JM. Clinical Indications for digital imaging in dento-alveolar trauma. Part 2: root resorption. Dent Traumatol 2007;23:105–13.

18. Kahler B, Heithersay GS. An evidence-based appraisal of splinting luxated, avulsed and root-fractured teeth. Dent Traumatol 2008;241:2–10.

19. Andreasen JO, Andreasen FM, Mejare´ I, Cvek M. Healing of 400 intra-alveolar root fractures 2. Effect of treatment factors such as treatment delay, repositioning, splinting type and period and antibiotics. Dent Traumatol 2004;20:203–11.

20. Hinckfuss SE, Messer LB. An evidence-based assessment of the clinical guidelines for replanted avulsed teeth. Part II: prescription of systemic antibiotics. Dent Traumatol 2009;25:158–64.

21. Cvek M. A clinical report on partial pulpotomy and capping with calcium hydroxide in permanent incisors with complicated crown fractures. J Endod 1978;4:232–7.

22. Fuks AB, Bielak S, Chosak A. Clinical and radiographic assessment of direct pulp capping and pulpotomy in young permanent teeth. Pediatr Dent 1982;4:240–4.

23. Olsburgh S, Jacoby T, Krejei I. Crown fractures in the permanent dentition: pulpal and restorative considerations. Dent Traumatol 2002;18:103–15.

24. Witherspoon DE. Vital pulp therapy with new materials: new directions and treatment perspectives – permanent teeth. Pediatr Dent 2008;30:220–4.

25. Huang GT. A paradigm shift in endodontic management of immature teeth: conservation of stem cells for regeneration. J Dent 2008;36:379–86. Epub 16 April 2008.

26. Chueh LH, Ho YC, Kuo TC, Lai WH, Chen YH, Chiang CP. Regenerative endodontic treatment for necrotic immature permanent teeth. J Endod 2009;35:160–4. Epub 12 December 2008.

27. Bose R, Nummikoski P, Hargreaves K. A retrospective evaluation of radiographic outcomes in immature teeth with necrotic root canal systems treated with regenerative endodontic procedures. J Endod 2009;35:1343–9. Epub 15 August 2009.

28. Thibodeau B, Trope M. Pulp revascularization of a necrotic infected immature permanent tooth: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dent 2007;29:47–50.

29. Trope M. Treatment of the immature tooth with a non-vital pulp and apical periodontitis. Dent Clin North Am 2010;54:313–24.

30. Jung IY, Lee SJ, Hargreaves KM. Biologically based treatment of immature permanent teeth with pulpal necrosis: a case series. J Endod 2008;34:876–87. Epub 16 May 2008.

31. Robertson A, Andreasen FM, Andreasen JO, Noren JG. Longterm prognosis of crown-fractured permanent incisors. The effect of stage of root development and associated luxation injuries. Int J Paediatr Dent 2000;103:191–9.

32. Holcomb JB, Gregory WB Jr. Calcific metamorphosis of the pulp; its incidence and treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1967;24:825–30.

33. Neto JJ, Gondim JO, de Carvalho FM, Giro EM. Longitudinal clinical and radiographic evaluations of severely intruded permanent incisors in a pediatric population. Dent Traumatol 2009;25:510–24.

34. Robertson A. A retrospective evaluation of patients with uncomplicated crown fractures and luxation injuries. Endod Dent Traumatol 1998;14:245–56.

35. Amir FA, Gutmann JL, Witherspoon DE. Calcific metamorphosis: a challenge in endodontic diagnosis and treatment. Quintessence Int 2001;32:447–55.

36. Andreasen FM, Andreasen JO, Bayer T. Prognosis of root fractured permanent incisors; prediction of healing modalities. Endod Dent Traumatol 1989;5:11–22.

37. Andreasen JO, Andreasen FM, Skeie A, Hjörting-Hansen E, Schwartz O. Effect of treatment delay upon pulp and periodontal healing of traumatic dental injuries – a review article. Dent Traumatol 2002;18:116–28.

38. Andreasen JO, Bakland LK, Andreasen FM. Traumatic intrusion of permanent teeth. Part 3. A clinical study of the effect of treatment variables such as treatment delay, method of repositioning, type of splint, length of splinting and antibiotics on 140 teeth. Dent Traumatol 2006;22:99–111.

39. Kenny DJ, Barrett EJ, Casas MJ. Avulsions and Intrusions: the controversial displacement injuries. J Can Dent Assoc 2003;69:308–13.

40. Stewart C, Dawson M, Phillips J, Shafi I, Kinirons M, Welburg R. A study of the management of 55 traumatically intruded permanent incisor teeth in children. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 2009;10:25–8.

41. Albadri S, Zaitoun H, Kinirons MJ. UK National Clinical Guidelines in Paediatric Dentistry: treatment of traumatically intruded permanent incisor teeth in children. Int. J Pediatr Dent 2010;20(Suppl 1):1–2.

42. Andreasen JO, Bakland LK, Matras RC, Andreasen FM. Traumatic intrusion of permanent teeth. Part 1. An epidermiological study of 216 intruded permanent teeth. Dent Traumatol 2006;22:83–9.

43. Andreasen JO, Bakland LK, Andreasen FM. Traumatic intrusion of permanent teeth. Part 2. A clinical study of the effect of preinjury and injury factors such as sex, age, stage of root development, tooth location and extent of injury including number of intruded teeth on 140 intruded permanent teeth. Dent Traumatol 2006;22:90–8.

44. Wigen TI, Agnalt R, Jacobsen I. Intrusive luxation of permanent incisors in Norwegians aged 6–17 years: a retrospective study of treatment and outcome. Dent Traumatol 2008;24:612–8.

45. Ebeleseder KA, Santler G, Glockner K, Huller H, Perfl C, Quehenberger F. An analysis of 58 traumatically intruded and surgically extruded permanent teeth. Dent Traumatol 2000;16:34–9.

46. Humphrey JM, Kenny DJ, Barrett EJ. Clinical outcomes for permanent incisor luxations in a pediatric population. I. Intrusions. Dent Traumatol 2003;19:266–73.

47. Al Badri S, Kinirons M, Cole B, Welbury R. Factors affecting resorption in traumatically intruded permanent incisors in children. Dent Traumatol 2002;18:73–6.

48. Andreasen JO, Andreasen FM, Mejare´ I, Cvek M. Healing of 400 intra-alveolar root fractures. l. Effect of pre-injury and injury factors such as sex, age, stage of root development, fracture type, location of fracture and severity of dislocation. Dent Traumatol 2004;20:192–202.

49. Cvek M, Andreasen JO, Borum MK. Healing of 208 intraalveolar root fractures in patients aged 7–17 years. Dent Traumatol 2001;17:53–62.

50. Welbury RR, Kinirons MJ, Day P, Humphreys K, Gregg TA. Outcomes for root-fractured permanent incisors; a retrospective study. Pediatr Dent 2002;24:98–102.

51. Cvek M, Meja´ re I, Andreasen JO. Healing and prognosis of teeth with intra-alveolar fractures involving the cervical part of the root. Dent Traumatol 2002;18:57–65.

52. Cvek M, Tsillingaridis G, Andreasen JO. Survival of 534 incisors after intra-alveolar root fracture in 7–17 years. Dent Traumatol 2008;24:379–87.

53. Farsi N, Alamoudi N, Balto K, Al Muskagy A. Clinical assessment of mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) as direct pulp capping in young permanent teeth. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2006;31:72–6.

54. Moule AJ, Moule CA. The endodontic management of traumatized anterior teeth: a review. Aust Dent J 2007; 52(Suppl 1):S122–37.

55. Bakland LK. Revisiting traumatic pulpal exposure: materials, management principles and techniques. Dent Clin N Am 2009;53:661–73.

56. Cavalleri G, Zerman N. Traumatic crown fractures in permanent incisors with immature roots: a follow-up study. Endod Dent Traumatol 1995;11:294–6.

57. Ferrazzini Pozzi EC, von Arx T. Pulp and periodontal healing of laterally luxated permanent teeth; results after 4 years. Dent Traumatol 2008;24:658–62.

58. Nikoui M, Kenny DJ, Barrett EJ. Clinical outcomes for permanent incisor luxation in a pediatric population. III. Lateral luxations. Dent Traumatol 2003;19:280–5.

59. Jackson NG, Waterhouse PJ, Maguire A. Factors affecting treatment outcomes following complicated crown fractures managed in primary and secondary care. Dent Traumatol 2006;22:179–85.

60. About I, Murray PE, Franquin JC, Remusat M, Smith AJ. The effect of cavity restoration variables on odontoblast cell numbers and dental repair. J Dent 2001;29:109–17.

61. Murray PE, Smith AJ, Windsor LJ, Mjor IA. Remaining dentine thickness and human pulp responses. Int Endod J 2003;36:33–43.

62. Subay RK, Demirci M. Pulp tissue reactions to a dentin bonding agent as a direct capping agent. J Endod 2005;31:201–4.

63. Bogen G, Kim JS, Bakland LK. Direct pulp capping with mineral trioxide aggregate: an observational study. J Am Dent Assoc 2008;139:305–15.

64. Cvek M, Meja´ re I, Andreasen JO. Conservative endodontic treatment in the middle or apical part of the root. Dent Traumatol 2004;20:261–9.

65. Hinckfuss S, Messer LB. Splinting duration and periodontal outcomes for replanted avulsed teeth, a systematic review. Dent Traumatol 2009;25:150–7.

66. Oikarinen K. Tooth Splinting – a review of the literature and consideration of the versatility of a wire-composite splint. Endod Dent Traumatol 1990;6:237–50.

67. VonArx T, Fillipi A, Lussi A. Comparison of a new dental trauma splint device (TTS) with three commonly used splinting techniques. Dent Traumatol 2001;17:266–74.

68. Berthold C, Thaler A, Petschelt A. Rigidity of commonly used dental trauma splints. Dent Traumatol 2009;25:248–55.

69. Andreasen JO, Storgaard Jensen S, Sae-Lim V. The role of antibiotics in presenting healing complications after traumatic dental injuries: a literature review. Endod Topics 2006;14:80–92.