Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Revista Brasileira de Odontologia

versão On-line ISSN 1984-3747versão impressa ISSN 0034-7272

Rev. Bras. Odontol. vol.73 no.4 Rio de Janeiro Out./Dez. 2016

Original Article/Oral Pathology

Oral manifestations and histopathology of minor salivary gland from patients with Sjögren's Syndrome and its diagnosis in a public health system

Elizângela Cristina BarbosaI; Jéssica Bruna Corrêa LindosoI; Nikeila Chacon de Oliveira CondeI; Luiz Fernando de Souza PassosII; Sandra Lúcia Euzébio RibeiroII; Jeconias CâmaraIII; Tatiana Nayara Libório-KimuraIII

I School of Dentistry, Federal University of Amazonas, Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil

II Department of Rheumatology, School of Medicine, Federal University of Amazonas, Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil

III Department of Pathology and Legal Medicine, School of Medicine, Federal University of Amazonas, Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil

ABSTRACT

Objective: to analyze the oral manifestations, sialometry and the histopathology of the minor salivary glands of patients with Sjögren Syndrome (SS) treated in a public health system and diagnosed according to European American Consensus Group (EACG) criteria. Material and Methods: the 32 patients were submitted to Shirmer test, oral cavity exam, unstimulated and stimulated salivary flow measurement and, in some cases, to the serological testing. For certain patients a minor salivary gland biopsy was carried out. Results: 10 patients were diagnosed with Sjögren Syndrome (SS), among whom: 40% were diagnosed with primary (pSS) and 60% with secondary Sjögren Syndrome (sSS). All patients diagnosed with this condition complained of xerostomia and xeropthalmia. Besides xerostomia, the most frequent oral manifestations were difficulty in swallowing, dry lips, hyperemic gums and atrophic change in tongue papillae. The average scores of the Schirmer and salivary flow tests were lower in patients with sSS. Conclusion: the oral signs and symptoms are extremely important in the multisystem involvement of the SS, which emphasizes the dental surgeon responsibility in managing these patients. The establishment of multidisciplinary diagnostic centers is of utmost importance, as well as the ability to offer more objective exams in the public health system aiming at increasing the accuracy of Sjögren Syndrome diagnosis.

Descriptors: Sjögren Syndrome; Xerostomia; Xerophthalmia, Diagnosis.

Introduction

Sjögren Syndrome (SS) is a chronic, inflammatory multisystem autoimmune disease, mainly involving the salivary and lacrimal glands. The condition is classified as primary Sjögren Syndrome (pSS), when it occurs by itself and as secondary Sjögren Syndrome (sSS), when it is associated to another autoimmune disease, among which the most frequent are Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) and Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA).1-3 Just like most of the immune complex- mediated diseases Sjogren Syndrome etiology is unknown and several studies already exist on possible triggering factors including: genetic, viral, immunological and hormonal factors.4,5

The most important manifestations of the Sjögren's Syndrome are dry eyes (xerophthalmia) and dry mouth (xerostomia), caused by lymphocyte infiltration into the glands, destroying the acinar units and causing hypofunction. There may also be extraglandular manifestations affecting kidneys, skin, lungs, muscles, liver, neurons, gastrointestinal tract and the thyroid. Patient history associated to oral cavity exam is extremely important to detect the signs and symptoms associated to xerostomia, as for example, filiform papillae atrophy, increased number of cavities, candidiasis, halitosis, altered sense of taste, burning feeling, difficulty in swallowing, among other.3,6,7

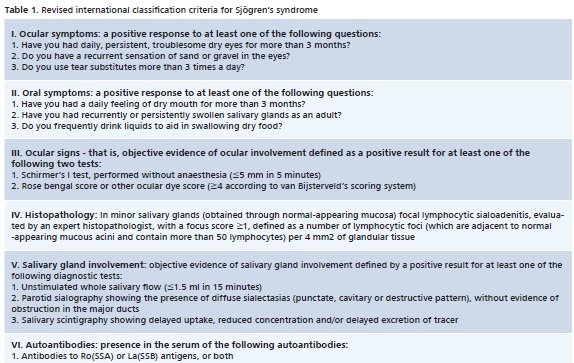

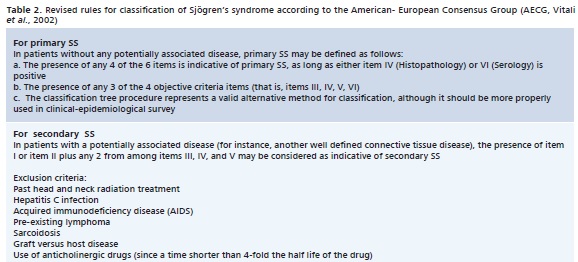

As it is complex and multidisciplinary, there is no specific test for Sjögren's Syndrome diagnosis.3 Among the criteria established for this purpose and selected for this study, is the soundly established criteria proposed by the American-European Consensus Group 2002 (AECG).8 Hence, diagnosis will depend on subjective items (sicca symptoms) and objective tests such as minor salivary gland biopsy to detect the existence of focal lymphocytic sialadenitis;2,9,10 immunological tests for Anti-SSA (RO) and Anti-SSB (La) nuclear antibodies and sialometry to detect hyposalivation2,10 and the Schirmer test to evaluate tear production.2

The objective of this study was to evaluate the oral manifestations and histopathological findings on minor salivary glands of patients suspected of SS, applying the AECG criteria for disease diagnosis, as well as to emphasize the need to offer more objective tests in the public health system to improve the application of diagnostic criteria.

Material e Methods

The project was granted approval by the Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Amazonas (UFAM), Brazil, (CAAE no. 0127.0.115.000-11 – 01/06/2011 CEP/UFAM). Patients suspected of SS treated at the Rheumatology Department of the Araújo Lima (AAL) outpatient unit were selected and examined by the Ophthalmology Department associated to the Federal University of Amazonas (UFAM), and referred to the UFAM School of Dentistry (FAO).

•Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The study included patients over 18 years of age, independent from gender, patients with SS or suspected of SS and those presenting symptoms of xerostomia and xerophthalmia. Patients using antihypertensive drugs, submitted to radiation or chemotherapy for head and neck cancer treatment, patients with pre-existing lymphomas, graft-vs-host disease, sarcoidosis, serious coagulopathy and pregnant women were excluded.

•Clinical Procedures

Patients were submitted to a multidisciplinary evaluation for Sjögren Syndrome Diagnosis, using the American European Consensus Group – AECG criteria (Table 1 and 2).

•Rheumatological Evaluation

Patients complaining of xerostomia and/or xerophthalmia were evaluated at the rheumatology outpatient unit, then submitted to anamnesis, to a physical examination, and also to a structured questionnaire about xerostomia and xerophthalmia and finally to an evaluation for the presence of systemic autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus or scleroderma, aiming at checking for a preliminary match to the criteria of the American European Consensus Group,8 at the AAL.

•Ophthalmological Evaluation

Standardized tests were carried out at the AAL, including visual acuity without and with correction, eye movement: preserved or altered, color test and Schirmer test with scores related to ≤5mm/5 min change (according to AECG parameters), at the AAL.

• Oral Evaluation

Patients referred to the UFAM School of Dentristry had they history collected, answered a structured questionnaire about oral symptoms and were submitted to clinical assessment of oral condition, looking for possible signs of SS. Among other, the presence of xerostomia, saliva consistency, dysphagia, changes in tongue, as for example, fissures or papillae atrophy, parotid enlargement and halitosis, were considered.

Next, unstimulated and stimulated salivary flow testing11 was conducted, following the ≤0.1 ml/min and < 0.7 ml/ min,12 parameters, respectively, as scores to detect a hyposalivation condition.

The unstimulated salivary flow test was carried out according to the spitting method recommended by Guebur and colleagues. Patient needed 1 hour fasting, and was told to rest for 6 minutes, with his head slightly lowered, and without moving his tongue or lips to accumulate saliva on mouth floor to be ultimately collected in a recipient. The saliva obtained in the first minute was discarded and saliva produced in the following 5 minutes collected, at 1 minute intervals, in a volumetric flask. After saliva collection, 3ml of distilled water were added and the sample was kept cooled at 6°C for 24 hours. After 24 hours, the sample was measured using a sterile 5ml syringe and the 3ml were then deducted.11 The amount of saliva, in ml, was divided by the duration of collection (5 min) to determine salivary flow.

For the stimulated salivary flow test, mechanical induction was carried out by chewing on a paraffin film (Parafilm®). The steps followed were identical to those designed for the unstimulated salivary flow test, referred to above, except for the addition of 3ml distilled water in the volumetric flask.

• Minor Salivary Gland Biopsy

Biopsy of minor salivary glands was carried out, where indicated, under local anesthesia with 2% lidocaine hydrochloride anesthetic salt, using the preferred local infiltration with block at distance anesthesia technique. The incision was made using a no. 15C scalp for an approximately 10mm final incision diameter at lower lip mucous membrane, in parallel to the lip redness region. Three to five salivary glands were removed by divulsion, without removing labial mucous membrane. Biopsy specimen was set with 10% formaldehyde and sent to the Surgical Pathology Department of the Pathology and Forensic Medicine Department (DPML) at UFAM, attached to a completed biopsy request form, for subsequent histological processing and microscopy analysis. The investigation was mainly focused on local lymphocytic sialadenitis around ducts as an agglomerated of at least 50 lymphocytes, and the final focal score was represented by the number of foci by 4 mm2 of gland tissue.9 Structural changes in glandular parenchyma, such as duct enlargement, acinar atrophy and replacement by fatty tissue were also considered.

Results

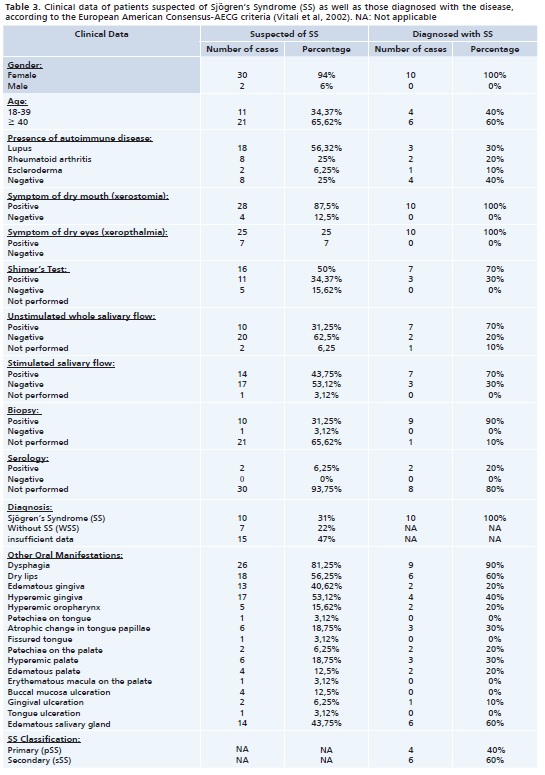

Thirty-two patients suspected of SS were examined between August, 2010 and May, 2012, with 94% (n = 30) represented by women, on average, aged 47 years. Data collected for these patients are shown in Table 3

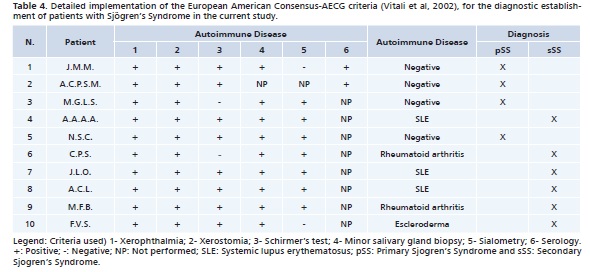

Among all patients examined, 31% (n = 10) were diagnosed with SS, 22% (n = 7) did not meet the diagnostic criteria for this disease, so without SS (WSS), and for 47% (n = 15) of these patients it was not possible to present enough exams for the diagnosis, being unfeasible according to the AECG classification criteria.8 Data collected for patients with SS, as well as the details of the application of the diagnostic criteria utilized for a final diagnosis are presented in Table 3 and 4.

Among patients diagnosed with SS 40% (n = 4) presented pSS and 60% (n = 6), sSS. Among patients with sSS, 50% (n = 3) were associated to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), 33% (n = 2) to rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and 17% (n = 1) to scleroderma.

Analysis of complaints of xeropthalmia and xerostomia revealed that both symptoms were reported by 57% of patients in the WSS Group, and by all patients in the pSS and sSS groups.

Dysphagia was reported by 57.15% of patients in the WSS Group, and 83% in the sSS Group.

The results of the comparison of the average scores of the Schirmer test, showed that WSS Group patients presented 16,8mm/5 minutes average, and those in the pSS Group 2.8mm/5 minutes average. That is, among patients diagnosed with the condition, those in the pSS Group had higher scores in the test when compared to sSS Group patients.

As to the analysis of the average scores of the unstimulated salivary flow test, patients in the WSS Group presented 0.292ml/minute average, those in the pSS Group 0.18ml/minute average and the sSS Group presented 0.047ml/minute average. For the stimulated salivary flow (SSF), the average results of patients in the WSS Group was 1.04ml/minute, for the pSS Group average was 0.67ml/minute and in the sSS Group the average was 0.38 ml/minute. It was then evidenced that also in these two tests, the pSS Group presented higher scores when compared to patients in the sSS Group.

In this study 11 biopsies were carried out, all of them in patients with at least one positive objective exam for SS, according to enforced criteria. All biopsies showed focal lymphocytic sialoadenitis in a minor salivary gland. Among these biopsies 9 were carried out in patients with histological results compatible with SS findings, namely, 3 in the pSS Group and 6 in the sSS Group. Note should be taken that one of the patients was diagnosed after other tests (other than a biopsy), including serology for Ro and/or La antibodies.

The three groups of patients (WSS, pSS and sSS) presented oral manifestations resulting from impaired salivary flow. The most frequent manifestations were: difficulty in swallowing, dry lips, gums and palate with edema and hyperemia and major salivary gland enlargement.

Discussion

SS is said to be a relatively common rheumatological disease affecting approximately 0.1 to 0.6% of the total population, and is 10 times more prevalent in women than in men.13,14It is rarely found in children, and the average onset happens around the fifth to the sixth decade of life.15,16 In this study, matching data found in the literature, all patients diagnosed with SS were women.

In the absence of a "gold standard" test for SS diagnosis, condition management is multidisciplinary and requires a team composed of stomatologists, oral pathologists, ophthalmologists and rheumatologists. Thus, many of the above mentioned specialists have been using the AECG8 classification criteria, which include subjective items such as xerostomia/xeropthalmia and oral, eye and rheumatology objective tests. Likewise, these criteria were also adopted in this study.

Once SS classification is broken down into primary disease, when it occurs by itself, and secondary disease when associated to another autoimmune disease,17 it is important to report that patients included in the study were referred by a Rheumatology Outpatient unit, that is, most (60%) of the diagnosed patients had already been diagnosed with another autoimmune disease, resulting in their classification as suffering from secondary Sjögren syndrome (sSS). It is believed that the best term would be "associated Sjögren syndrome" once there is no proof that an autoimmune disease facilitates the appearance of this syndrome.

Xerostomia and xeropthalmia, impaired saliva and tear production, respectively, constitute the leading SS symptoms, and were reported by all patients diagnosed in the course of the research. Hence, gland involvement, characteristic of the disease, resulting in organ dysfunction is evidenced.4

Serological testing is carried out to determine the presence of the Anti-SSA Ro and Anti-SSB La antibodies, which can be found in 75% of SS patients.18 The presence of both antibodies is not a rule, and they may appear separately. In this study, due to the difficulty patients face to take to be tested in the public health system, the weight of this test was compensated by carrying out other tests.

As to the eye variable, two tests may be carried out: test with Bengal rose eye staining that evidences eye irritation and conjunctival ulcers; and the Schirmer test that measure the degree of eye dryness.3,18 The Schirmer test revealed lower scores in patients with sSS, which is the opposite of the data found in the literature.19

There are three ways of carrying out the objective oral evaluation: 1) by sialography, where you look for the absence of the arborization found in gland ductal system, areas lacking parenchyma and punctiform sialectasia; 2) by scintigraphy to assess gland function; and by 3) sialometry (salivary flow), a method whereby saliva production is measured.3,20 Because of its accuracy and for being easy to perform, sialometry was the selected method for this study. It was carried out both by means of the unstimulated and the stimulated salivary flow test.12 The AECG criteria recommend carrying out just the unstimulated test, but both were used in in the study for comparison and additional information purposes. Additionally, Bookman20 reported a definitive association between the stimulated salivary flow and punctiform focal lesion and salivary gland fibrosis and the duration of dry mouth symptoms. In both tests, once again, it was evidenced that the sSS Group presented lower flow rate averages.

The presence of focal lymphocytic sialadenitis, where one or more foci of at least 50 lymphocytes may be found in a 4mm2 area is often characteristic of this condition and is detected by salivary gland biopsy.21 The biopsy can be carried out on minor salivary glands of labial mucous membrane or on the parotid gland.22 However, because of easier access and for being less invasive, for this study the minor salivary gland biopsy procedure was selected. Even if it is said to be one of the leading criteria when searching for a diagnosis, biopsy is not always necessary,3 as long as the other requirements of the AECG criteria are adequately provided and met. In our study, among the 10 patients diagnosed with SS, 9 were pinpointed by employing a positive minor salivary gland biopsy result as one of the criteria. Notwithstanding, just 1 case was diagnosed by combining other criteria established by the AECG.8

Several disorders may end up by mimicking SS symptoms, such as: amiloidosis, graft-vs-host disease, sarcoidosis, AIDS and IGG4-related disease, as well as hepatitis C treatment, chemotherapy and radiotherapy in the head and neck area for cancer treatment, use of antihypertensive (beta blockers), psychiatric (benzodiazepines) and parasympatholytic drugs that cause xerostomia. This is why they were all considered among the exclusion criteria for diagnostic classification.23

Oral manifestations are generally found in patients with SS and can considerably impair their quality of life. Symptoms such as filiform papillae atrophy, candidiasis, difficulty in swallowing and/or speaking, halitosis, altered sense of taste,7 and others, are generally due to xerostomia itself and thus, these symptoms are found in both the pSS and sSS groups. In our study, xerostomia was reported by all patients in both pSS and sSS groups. Dysphasia symptoms were reported by 90% of patients with SS, and dry lips by 60%, with such changes resulting also from impaired salivary flow. Salivary gland enlargement was found in 60% of patients with SS, which would be related to active disease, culminating in gland size enlargement.

Among the hindrances found in establishing a diagnosis of this condition, beside the lack of one single and precise test and the difficulty in ultimately setting up a multidisciplinary team for disease management, there is also the cyclic remission period and exacerbation of SS. Hence, long term patient follow-up should be recommended. As previously stated, conclusion of some cases requires serological tests, but several obstacles were faced to carry out the necessary tests for SS diagnosis in the public health system. As previously mentioned, the weight of this test was compensated by adopting other parameters accepted by the AECG criteria.8 Notwithstanding, in some cases serological tests are critical to a final conclusion. The difficulty found in carrying out the tests in the public health system may further hinder the use of the new American College Rheumatology criterion, published in 2012, that recommends for SS diagnosis just the use of objective tests, namely: 1) serology, 2) eye testing with Lissamine green and 3) minor salivary gland biopsy, thus evidencing the need to ask for and to make these tests feasible in the public health system.24

Consideration should be given to the fact that, in our study, out of the 32 patients suspected with SSj just 31% (n = 10) were actually diagnosed with the disease. All of them reported the classical symptoms of sicca syndrome (xerostomia and xeropthalmia), and were within the age range most frequently affected by this condition. However, two factors that interfere with disease diagnosis must be taken into consideration, on one side we have the diagnostic challenge itself which is inherent to this condition and, on the other, the unfeasibility of carrying out all the tests required for a final diagnosis. The sum of such factors could justify the relatively low count of patients diagnosed with SS in the study. Additionally, considering the actual incidence of the disease itself (from 0.1 to 0.6%)13,14 finding patients who meet the classification criteria is not always an easy task, which further underlines the need to establish SS diagnostic centers. As a result, we would see the consolidation of the reference centers for this disease, culminating in an increased demand from patients looking for specialized treatment, leading even to a more appropriate assistance.

SS is incurable and, therefore, treatment is symptomatic. The eye symptoms are treated by an ophthalmologist using resources such as artificial tears. Prescriptions for xerostomia include constant intake of liquids, avoiding use of alcohol and of any substances that may cause dehydration, use of flavorless and sugarless chewing gums to stimulate saliva production and the use of artificial saliva. A pharmacological therapy with cholinergic drugs such as pilocarpine, bethanechol and carbachol may also be used.2,3

Conclusion

SS diagnosis is a challenge and must involve a multidisciplinary team, above all a team composed of stomatologists, oral pathologists, ophthalmologists and rheumatologists. Besides, SS disease diagnosis in the public health system is hindered by the unfeasibility of carrying out all tests required. Therefore, in this scenario, the criteria set by the American- European Consensus Group (AECG) continue to be extremely useful, as its application approach continues to be more feasible for this target public. Such criteria (AECG) provide significant flexibility of application as the lack of certain exams may be compensated by other more practical and feasible tests, whose sum of positive results may reach the necessary scores for SS diagnosis. Last, the need for new approaches to this condition and the establishment of multidisciplinary nuclei are critical.

Acknowledgements

We thank the nurse Deiziane Epifânio and the dental student Jessica Hayden for their collaboration in the execution of practical activities of this project. This project was supported by the Federal University of Amazonas (UFAM) by the Institutional Scholarship Program for Scientific Initiation (PIBIC), being held at the Araújo Lima Outpatient Clinic of the School of Medicine and at the Stomatology Outpatient Clinic of the UFAM, School of Dentistry.

References

1 - Soto-Rojas AE, Kraus A. The oral side of Sjögren syndrome. Diagnosis and treatment. A review. Arch Med Res. 2002;33:95-106. [ Links ]

2 -Minozzi F, Galli M, Gallottini L, Minozzi M, Unfer V. Stomatological approach to Sjögren's syndrome: diagnosis, management and therapeutical timing. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2009;13(3):201-16.

3 - Kruszka P, O'brian RJ. Diagnosis and Management of Sjögren Syndrome. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79(6):465-70.

4 - Hayashi T. Dysfunction of Lacrimal and Salivary Glands in Sjogren's Syndrome: Nonimmunologic Injury in Preinflammatory Phase and Mouse Model. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011:1-15.

5 – Chiorini, JA, Cihakova D, Ouellettec CE, Caturegli P. Sjögren syndrome: Advances in the pathogenesis from animal models. J Autoimmun. 2009;33(3-4):190-6.

6 - Ergun S, Çekici A, Topcuoglu N, Migliari DA, Külekçi G, Tanyeri H, et al. Oral status and Candida colonization in patients with Sjögren's Syndrome. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2010;15(2):e310-5.

7 – Margaix- Muñoz M, Bagán JV, Poveda R, Jiménez Y, Sarrión G. Sjögren's syndrome of the oral cavity. Review and update. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2009;14(7):e325-30.

8 - Vitali C, Bombardieri S, Jonsson R, Moutsopoulos HM, Alexander EL, Carsons SE, et al. Classification criteria for Sjögren's syndrome: a revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American-European Consensus Group. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61(6):554-8.

9 - Morbini P, Manzo A, Caporali R, Epis O, Villa C, Tinelli C, et al. Multilevel examination of minor salivary gland biopsy for Sjögren's syndrome significantly improves diagnostic performance of AECG classification criteria. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7(2):R343-8.

10 - Liquidato BM, Bussoloti Filho I. Evaluation of sialometry and minor salivary gland biopsy in classification of Sjögren's Syndrome patients. Rev Bras Otorrinolaringol. 2005;71(3):346-54.

11 - Guebur MI, Rapoport A, Sassi LM, Oliveira BV, Pereira JCG, Ramos GHA. Alterations of total non stimulated salivary flow in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the mouth and oropharynx submitted to hyperfractionated radiation therapy. Rev. Bras. Cancerol. 2004;50(2):103-8.

12 – von Bültzingslöwen I, Sollecito TP, Fox PC, Daniels TE, Jonsson R, Lockhart PB, et al. Salivary dysfunction associated with systemic diseases: systematic review and clinical management recommendations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103(suppl: S57):e1-15.

13 -Delaleu N, Nguyen CQ, Peck AB, Jonsson R. Sjogren's syndrome: studying the disease in mice. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13(3):217.

14 - Theander E, Manthorpe R, Jacobsson LT. Mortality and causes of death in primary Sjögren's syndrome: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(4):1262-69.

15 - Albuquerque ACL, Vieira JP, Soares MSM, Rego BFPT. Síndrome de Sjögren: relato de caso. Com. Ciências Saúde. 2008;19(1):71-7.

16 - Liquidato BM, Bussoloti-Filho I. Evaluation of sialometry and minor salivary gland biopsy in classification of Sjögren's Syndrome patients. Rev Bras Otorrinolaringol. 2005;71(3):346-54.

17 - Larrarte JPM, Pineda YR. Sjögren syndrome. Revista Cubana de Medicina 2010; 49(2): 61-76.

18 - Bezerra TP, Pita Neto IC, Dias EOS, Gomes ACA. Síndrome de Sjögren Secundária: revista de literatura e relato de caso clínico. Arq. Odontol. 2010;46(4).

19 – Hernández-Molina G, Avila-Casado C, Cárdenas-Velázquez F, Hernández-Hernándes C, Calderillo ML, Marroquín V, et al. Similarities and differences between primary and secondary Sjögren's syndrome. J Rheumatol. 2010;37(4):800-8.

20 - Bookman AA, Shen H, Cook RJ, Bailey D, McComb RJ, Rutka JA, et al. Whole stimulated salivary flow: correlation with the pathology of inflammation and damage in minor salivary gland biopsy specimens from patients with primary Sjögren's syndrome but not patients with sicca. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(7):2014-20.

21 - Scardina GA, Spanò G, Carini F, Spicola M, Valenza V, Messina P, et al. Diagnostic evaluation of serial sections of labial salivary gland biopsies in Sjögren's syndrome. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2007;12(8):E565-8.

22 - Soyfoo MS, Catteau X, Delporte C. Parotid Gland Biopsy as an Additional Diagnostic Tool for Supporting the Diagnosis of Sjogren's Syndrome. Int J Rheumatol. 2011;1-4.

23 - Gomes RS, Brandalise R, Alba GP, Flato UA, Júnior JEM. Síndrome de Sjögren primária. Rev Bras Clin Med. 2010;8(3):254-65.

24 - Shiboski SC, Shiboski CH, Criswell LA, Baer AN, Challacombe S, Lanfranchi H, et al. American College of Rheumatology Classification Criteria for Sjogren's Syndrome: A Data-Driven, Expert Consensus Approach in the Sjogren's International Collaborative Clinical Alliance Cohort. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64(4):475-87.

Endereço para correspondência:

Endereço para correspondência:

Tatiana Nayara Libório Kimura

e-mail: tliborio@ufam.edu.br

e-mail: tatiana.liborio@gmail.com

Recebido: 31/08/2016

Aceito: 10/05/2016