Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

RGO.Revista Gaúcha de Odontologia (Online)

versão On-line ISSN 1981-8637

RGO, Rev. gaúch. odontol. (Online) vol.60 no.1 Porto Alegre Jan./Mar. 2012

ORIGINAL / ORIGINAL

Students' and general population's knowledge about the use and commerce of human teeth

Conhecimento de discentes e da população em relação à utilização e ao comércio de órgãos dentários

Sílvia Helena de Carvalho SALES PERES I; Marina Duarte GARCIA II; André de Carvalho SALES PERES II; Adriana Rodrigues de FREITAS I; Patrick Henry Machado ALVES II; Arsenio SALES PERES I

I Universidade de São Paulo, Faculdade de Odontologia, Departamento de Odontopediatria, Ortodontia e Saúde Coletiva. Al. Octávio Pinheiro Brisolla, 9-75, 17012-901, Bauru, SP, Brasil

II Universidade de São Paulo, Faculdade de Odontologia. Bauru, SP, Brasil

ABSTRACT

Objective

This study investigated undergraduates' and general population's knowledge about the methods used for tooth procurement and donation and their destination.

Methods

The sample consisted of all undergraduates from a public institution (n=200) and 500 residents from the city of Bauru, São Paulo. They were asked to answer a self-explanatory questionnaire.

Results

A total of 56.5% and 71.6% of undergraduates and Bauru residents, respectively, answered the questionnaire. Statistical analysis was based on absolute and relative frequencies. The results showed that 88.5% of the undergraduates had already used human teeth in laboratory activities and at least 8% of them had also used human teeth in research. Most (80.5%) teeth came from donations. Some (59.3%) study participants kept the unused teeth and some (29.2%) donated them. Bauru residents reported that dental surgeons hardly ever asked them to donate their teeth and demonstrated little knowledge about the existence of tooth banks, although most had already extracted at least one tooth.

Conclusion

The results suggest that undergraduates have difficulty implementing measures for tooth use and procurement. Activities of human tooth banks need to be disclosed not only to undergraduates but also to the general population.

Indexing terms: Bioethics. Legislation. Organ and tissue procurement. Tooth.

RESUMO

Objetivo

Analisar o conhecimento dos acadêmicos de graduação de uma instituição pública e da população em geral, sobre os métodos adotados para a aquisição, doação e destinação de órgãos dentários.

Métodos

A amostra foi composta de todo o universo de graduandos (n=200) e por 500 indivíduos residentes em Bauru, São Paulo, os quais receberam um questionário auto-explicativo.

Resultados

Houve devolução de 56,5% dos questionários respondidos por graduandos e 71,6% dos respondidos pela população. A análise estatística foi realizada por meio de frequências absolutas e relativas. Os resultados demonstraram que 88,5% dos acadêmicos já utilizaram dentes humanos em atividades laboratoriais e pelo menos 8,0% deles utilizaram também em pesquisa. Quanto à aquisição de órgãos dentários, verificou-se que 80,5%, ocorrem por meio de doações. Os participantes da pesquisa afirmaram que 59,3% guardavam e 29,2% doavam os dentes não utilizados. A população relatou que o profissional quase nunca solicitou a doação do órgão dentário e demonstrou ter baixo conhecimento em relação à existência de banco de dentes, embora a maioria já tivesse extraído algum dente.

Conclusão

Os resultados sugerem que os acadêmicos têm dificuldades na adoção de medidas para o uso e a aquisição de órgãos dentários. Há a necessidade de divulgação das atividades dos bancos de dentes humanos não só no meio acadêmico, mas para toda a população.

Termos de indexação: Bioética. Legislação. Obtenção de tecidos e órgãos. Dente.

INTRODUCTION

Knowledge is the main innovation factor available to the human being. Although knowledge is not necessarily produced at the university, it is there that most scientific knowledge and technology are produced. The incorporation and interrelationship of teaching and pedagogical methods, practical areas and experience should include the appreciation of moral, ethical and legal precepts.

It is necessary to study bioethics routinely in dentistry courses, especially because of the obscure points that still exist regarding the use of human teeth and the ethical and bioethical aspects associated with the subject1.

The term bioethics was coined in 1970 in by the oncologist Van Rensselaer Potter in an article called "The science of survival," and used again in the following year in a book written by the same author entitled "Bioethics: bridge to the future2."

Bioethics can be defined as the systematic study of human conduct in the scope of life and health sciences examined under the light of moral values and principles3.

In this sense, bioethics is a bridge between sciences and mankind. It takes into account the danger that results from the splitting of the two areas of knowledge, scientific and humanistic knowledge, to the survival of the entire ecosystem4-5.

Some legislation has been created to guide this relationship, such as Nuremberg Code, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Declaration of Helsinki, among others1.

When one analyzes the four principles that guide bioethics, namely autonomy, benevolence (obligation to do good to other people), no malevolence (further professional commitment not to harm others) and justice (equity)6, one ponders about how educational institutions and society deal with the relationships among research, laboratory training and use of human teeth.

In dentistry, the issue of using human teeth is frequently present when discussions focus on the ethical aspects of research involving human beings. This stems from the fact that the reuse of dental elements occurs by the use of enamel fragments in restorative procedures7, dental crowns in the fabrication of prosthetic appliances8, fabrication of space-holders1, student training in laboratories and research of the most diverse areas9.

Conceptually, human teeth are organs of the human body. They consist of different tissues in variable proportions and have specific functions and recognizable shape10.

When people sell or buy teeth, they may be charged of a crime defined by penal and/or civil law, and not knowing that these activities are criminal does not exempt one from punishment, since article 3 of the Brazilian Civil Code1 states that not knowing a law does not exempt one from punishment for infringement.

The legal aspect is also emphasized. Article 15 of the Brazilian Civil Code11 establishes a prison sentence of 3 to 8 years, in addition to a fine, for those who buy or sell tissues, organs or parts of the human body. Article 210 of the Brazilian Penal Code12 establishes that those who violate or desecrate a grave or morgue are subject to a fine and prison sentence of 1 to 3 years.

Research involving human beings is regulated by Resolution 196/9613 of the Ministry of Health. It is important to mention that professors who ask students to use human material of unknown origin can be charged with encouraging a crime according to the current legislation.

According to Imparato9 the main objective of establishing and disclosing human tooth banks is to make people aware of the importance of dental elements and to avoid the illegal commerce of human teeth, used in dentistry courses. Furthermore, as reported by Imparato9, the issue of the ethics associated with the use of human teeth in scientific research regards the origin of these organs, since it is necessary to get a free and informed consent form signed by the donors to use their teeth.

Human tooth banks is also very important for academia, since undergraduate dentistry students use teeth to study their most relevant anatomic characteristics which promotes more appropriate sculpturing patterns on dental restorations14. Additionally, one of the main use for human teeth is preclinical laboratory training in disciplines such as endodontics, dentistry and prosthetics.

In order to reinforce the need of actions for the implementation and disclosure of human tooth banks, Gabrielli et al.15 performed a study in the state of São Paulo where they found that 47% of the study participants had already bought teeth for use in laboratory or research. They also investigated the fate of the remainder teeth and found that they were either donated to peers (44%), sold (9%), discarded (15%), donated to a tooth bank (2%) or kept for future use or as a souvenir (30%).

Disclosing human tooth banks is critical for their growth and development of their functions. Disclosure will promote appreciation for the importance of teeth, increase the number of donations and, consequently, the number of activities done with them (such as research and preclinical laboratory studies), and reduce their commerce16.

The same authors reported that the disclosure of human tooth banks can be done through educational activities, lectures, posters and folders. It is important to make both the general population and scientific community aware of the cultural, bioethical, social, legal and moral importance of human tooth banks, like organ banks16.

The bank of human teeth from the University of São Paulo Bauru School of Dentistry is an interdisciplinary, nonprofit department that aims to inform people of how human teeth are used in academia. Its medium- and long-term objective is to aid teaching and research in the above mentioned school, giving academics and students the means of operationalizing their studies when human teeth are required.

Their responsibilities include the procurement, preparation, disinfection, manipulation, selection, preservation, storage, donation, lending and administration of donated teeth. All procedures are scientifically endorsed and follow sanitary surveillance norms.

Hence, studies that focus on restructuring strategies for the implementation and popularization of human tooth banks are urgently needed to abolish associated illegal activities.

This study investigated how dentistry undergraduates from a public institution procure dental elements and what a sample of the local population (Bauru residents) knows about human tooth banks and their importance.

METHODS

Ethical Aspects

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of São Paulo Bauru School of Dentistry (FOB/USP) in March 2006, protocol number 162/2005.

Inclusion criteria

All FOB/USP undergraduates (n=200) were invited to participate and given a self-explanatory questionnaire to determine their knowledge about tooth use, storage and donation. However, only 113 students agreed to participate in the study, that is, only 56.5% of the questionnaires were filled out. All participants signed a free and informed consent form.

Five-hundred Bauru residents were randomly selected in the 5 regions of the city and invited to answer an objective questionnaire. Only 358 residents agreed to participate in the study and filled out the questionnaires.

Microsoft Excel was used for the statistical treatment of the data which was analyzed descriptively and expressed in figures and tables as absolute and relative frequencies.

RESULTS

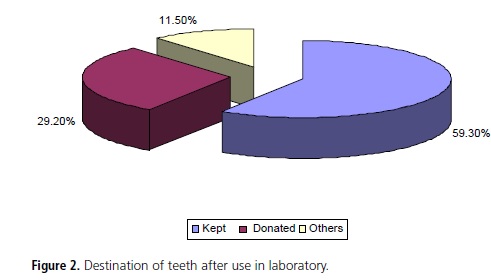

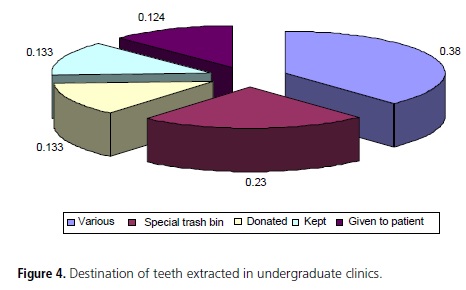

The results showed that 88.5% of the undergraduates had already used human teeth in laboratory activities and at least 8% had also used them in research. Most teeth (80.5%) had been donated to them by dental surgeons or academics. Some participants (59.3%) kept the unused teeth and some (29.2%) donated them. The fate of the teeth extracted at the clinics was also investigated: 13.3% were stored by undergraduates, 12.4% were given to the patient, 13.3% were donated to undergraduates or graduates, 23.0% were discarded in a special waste bag and 38.0% had other fates.

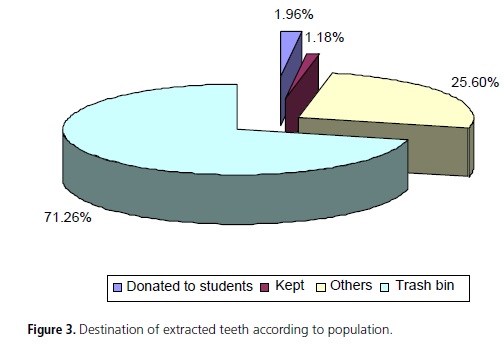

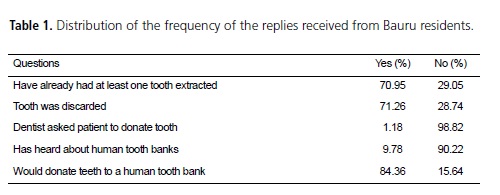

With respect to the sample of Bauru residents, 70.95% reported already having had at least one tooth extracted and 71.26% of these teeth were discarded in common trash bins. Nearly everyone (98.82%) stated that their dentist did not ask them to donate the extracted tooth and again, nearly everyone (90.22%) was unaware of the existence of human tooth banks. Most respondents (84.36%) were also willing to donate their teeth if their dental surgeon had asked. This population included people who had already had at least one tooth extracted (84.25%) and those who had not (84.61%).

DISCUSSION

In dentistry, the use of human teeth in laboratory and research is commonplace. Hence, bioethics needs to be taught routinely in dentistry courses, especially with respect to the procurement, use and storage of human teeth and the respective ethical and bioethical aspects9 because dentistry students do now know how to procure, store and discard human teeth correctly.

Once a work protocol is established and the population is made aware of the existence of human tooth banks, some of these problems would be solved. This would also inhibit the criminal commerce of human teeth, knowingly used by dentistry students9.

The literature still contains points that need clarification with regard to tooth donation and storage and the importance of tooth banks, especially in higher education institutions.

Regarding the commerce of human teeth, Article 6° the Law n° 9.43417, passed on February 04, 1997, states that the post-mortem removal of tissues, organs or parts of the body of unidentified individuals is forbidden. Article 15° of the same law states that anyone who buys or sells tissues, organs or parts of the human body is subject to a prison sentence of 3 to 8 years and a fine of 200 to 360 days-fine. The same sentence applies to those who promote, intermediate, facilitate or gain any advantage with the transaction.

Chapter II of the Brazilian Penal Code lists the crimes against the respect for the deceased. Article 210 states that those who violate or desecrate a grave or a funeral home are subject to a prison sentence of 1 to 3 years and a fine.

In 1997, when a new transplant law17 was passed in Brazil, teeth were identified as organs to discourage the illegal commerce of human teeth.

All professionals, students, professors and opinion leaders who do not yet follow the norms strictly need to be aware of the proper ethical and legal use of human teeth in research or clinical or laboratory procedures and start walking in the right direction by, for example, not encouraging the illegal commerce of organs, allowing the rational use of teeth in the future9.

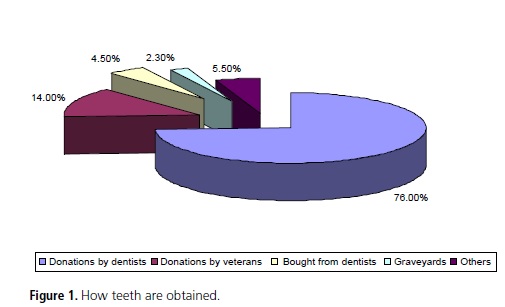

The results showed that dentistry courses require the use of human teeth in laboratory and research activities and most interviewees stated that they had already used teeth in college, which is in agreement with some literature reports18-20. The procurement of human teeth is commonplace among dentistry students, despite donations made by other students and professionals (Figure 1). Most participants reported keeping extracted teeth (Figure 2).

Human tooth banks are responsible for obtaining enough teeth to meet the demands of the institutions that rely on them. Hence, it is important to use different forms of procurement, which may be achieved through partnerships. Procurement sources can be diverse: private clinics, primary health facilities, educational clinics, hospitals, students, researchers and the general population16.

Gabrielli et al.15 conducted a study on human tooth banks and found that almost half the interviewees donated extracted teeth to their peers. In the present study, more than half saved the teeth for later use (Figure 2). On the other hand, most teeth extracted from the general population were discarded (Figure 3). Other destinations of these teeth were allowing the patient keep to it, donation to higher education students and disposal in special waste bins (Figure 4). Undergraduate clinics must ask patients if they accept to donate extracted teeth and inform them of the destination of their teeth, that is, how they will be used.

The destination of the teeth extracted in undergraduate clinics varies greatly but teeth are usually given to the patient (Figure 4).

Students having access to human tooth banks9 inhibits them from having to resort to illegal practices to obtain teeth15. Undergraduate students should know that human tooth banks lend teeth for a period of time, normally determined by the requesting discipline(s). In this case, the students need to be registered and return the teeth at the end of the period, regardless of their state, for them to be reused, if possible16.

Human tooth banks have been offering an ethical way to control the use and abuse of very common academic practices. They are also responsible for preventing the cross-contamination that occurs when extracted teeth are handled indiscriminately16,18-20.

Standardized criteria are necessary for human tooth storage and donation. This would contribute to the reorganization of concepts within bioethical principles. So, it is critical to control the internal procedures of human tooth banks strictly. Some of these procedures involve tooth categorization and storage and keeping records of donors and beneficiaries16.

Most of the interviewed Bauru residents had already had at least one tooth extracted. Most of the teeth were discarded (Table 1). This is lamentable because the demand for human teeth is very high, both in teaching and research21-22.

Only 1.2% of the participants reported that their dental surgeons asked them to donate the extracted teeth (Table 1), evidencing the low participation of these professionals in providing advice regarding tooth disposal, storage and donation.

The need of making individuals aware about the importance of teeth was emphasized by Imparato9. Very few individuals are aware of the existence of human tooth banks (Table 1). The media would need to get involved to make more people aware of their existence and to inform people of the importance of human teeth for teaching institutions and research, and how to care for them. Knowing the origin of a tooth allows social value to be aggregated to the donated organ, generating greater compromise and commitment of all those involved23.

The findings of this study indicate that the population needs more information about human tooth bank issues and their donation and disposal criteria18-20. This fact reinforces the importance of performing educational campaigns about tooth donation and storage.

Scientific evidence shows that it is very important to structure human tooth banks, not only to procure teeth ethically and legally but also to encourage actions that prevent cross-contamination and cross infections stemming from teeth of unknown origin.

The population needs to be sufficiently educated to demand that professionals store and request tooth donations bioethically.

CONCLUSION

The results indicate that undergraduates have difficulties to use and procure human teeth ethically. It is necessary to implement a human tooth bank in higher education institutions to use and store teeth correctly, following bioethical principles. On the other hand, the population demonstrated having little knowledge about the importance of human tooth banks.

In conclusion, it is necessary to disclose the activities of human tooth banks not only to academia but also to the general population to inhibit illegal commerce of human teeth and improve their destination.

Collaborators

SHC SALES PERES conceived, planned and developed the methodology, and helped to analyze the results and the writing of the article. MD GARCIA, AC SALES PERES and PHM ALVES participated in data collection and writing of the article. AR FREITAS helped to tabulate the data and write the article. A SALES PERES helped to organize the databank and the writing of the article.

REFERENCES

1. Silva M. Compêndio de odontologia legal. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan; 1997. [ Links ]

2. Sgreccia E. Manual de bioética I: fundamentos e ética médica. São Paulo: Edições Loyola; 1996.

3. Pessini L, Barchifontaine CP. Problemas atuais de bioética. São Paulo: Edições Loyola; 1997.

4. Potter VR. Bioethics: bridge to the future. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall; 1971.

5. Potter VR. Bioethics: the science of survival. Perspect Biol Med. 1970;14(1):127-53.

6. Garrafa V. Bioética e odontologia. In: Kriger L. Promoção de saúde bucal. São Paulo: Artes Médicas; 2003. p. 495-504.

7. Iorio PAC. Inlays de resina composta: seu emprego reforçado com fragmentos de esmalte reconstituindo a crista marginal. Rev Bras Odontol. 1993;50(6):3-7.

8. Hayward DE. Use of natural upper anterior teeth in complete dentures. J Prosthet Dent. 1968;19(4):359-63.

9. Imparato JCP. Banco de dentes humanos. Curitiba: Editora Maio; 2003.

10. Junqueira LC, Carneiro J. Histologia básica. 7ª ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan; 1990.

11. Brasil. Código Civil Brasileiro. Brasília: Senado Federal; 2003.

12. Brasil. Código Penal Brasileiro. Brasília: Senado Federal; 1940.

13. Brasil. Resolução 196, de 16 de outubro de 1996. Aprova as diretrizes e normas regulamentadoras de pesquisas envolvendo seres humanos. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília (DF); 1996 Out 16.

14. Wanderley MT, Mathias RS. Alternativa reabilitadora em avulsão de dentes decíduos. In: 13º Livro Anual do Grupo Brasileiro de Professores de Ortodontia e Odontopediatria. São Paulo: Grupo Brasileiro de Professores de Ortodontia e Odontopediatria; 1997. p. 92.

15. Gabrielli Filho PA, Imparato JCP, Guedes-Pinto AC. Comércio de dentes humanos nas faculdades de odontologia do Estado de São Paulo: resultados parciais [resumo]. RPG Rev Pos-Grad. 1999;6(3):229.

16. Nassif ACS, Tieri F, Ana PA, Botta SB, Imparato JCP. Estruturação de um banco de dentes humanos. Pesq Odontol Bras. 2003;17(Suppl 1):70-4.

17. Brasil. Lei n. 9.434, de 4 de fevereiro de 1997. Dispõe sobre a remoção de órgãos, tecidos e partes do corpo humano para fins de transplante e tratamento e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília (DF); 1997 Fev 5.

18. Garbin CAS, Garbin AJI, Santos KT, Pacheco Filho AC. Percepção de acadêmicos de Odontologia sobre clonagem, doação de órgãos e banco de dentes. RPG Rev Pos-Grad. 2008; 15(4):255- 60.

19. Pinto SL, Silva SP, Barros LM, Tavares EP, Silva JBOR, Freitas ABDA. Conhecimento popular, acadêmico e profissional sobre o banco de dentes humanos. Pesq Bras Odontoped Clin Integr. 2009;9(1):101-6.

20. Maggioni AR, Scelza MFZ, Silva LE, Salgado VE, Borges DO, Maciel ACC. Banco de dentes humanos na percepção dos acadêmicos da faculdade de odontologia da Universidade Federal Fluminense. Rev Flum Odontol. 2010;16(33):27-30.

21. Dewald JP. The use of extracted teeth for in vitro bonding studies: a review of infection control considerations. Dent Mater. 1997;13(2):74-81.

22. Shafer SE, Barkmeier WW, Gwinnett AJ. Effect of disinfection/ sterilization on in vitro enamel bonding. J Dent Educ. 1985; 49(9):658-9.

23. Poletto MM, Moreira M, Dias MM, Lopes MGK, Lavoranti OJ, Pizzatto E. Banco de dentes humanos: perfil sócio-cultural de um grupo de doadores. RGO - Rev Gaúcha Odontol. 2010;58(1):91- 4.

Correspondence to:

Correspondence to:

SHC SALES PERES

e-mail: shcperes@usp.br

Received on: 25/8/2010

Approved on: 17/4/2011