Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

RPG. Revista de Pós-Graduação

versão impressa ISSN 0104-5695

RPG, Rev. pós-grad. vol.19 no.3 São Paulo Jul./Set. 2012

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Glucose control in diabetes type 2 after oral minor surgery procedures

Controle da glicemia em pacientes com diabetes tipo 2 após cirurgia odontológica

VERA REGINA PEREIRA POZZANII; ANA CAROLINA JUNQUEIRAII; ANDREIA APARECIDA TRAINAIII; MARIA DA GRAÇA NACLÉRIO-HOMEMIV; MARIA CRISTINA ZINDEL DEBONIIV

I MD, Oral Surgery Department, Faculdade de Odontologia da Universidade de São Paulo (USP) – São Paulo/SP, Brazil

II BDS, trainee researcher, Oral Surgery Department, Faculdade de Odontologia da Universidade de São Paulo (USP) – São Paulo/SP, Brazil

III BDS, MDs, Assistant Professor, Oral Surgery Department, Faculdade de Odontologia da Universidade de São Paulo (USP) – São Paulo/SP, Brazil

IV BDS, MDs, PhD, Associate Professor, Oral Surgery Department, Faculdade de Odontologia da Universidade de São Paulo (USP) – São Paulo/SP, Brazil

ABSTRACT

The aims of this study were to investigate if surgical removal of oral infectious foci has effect on metabolic glucose level control 30 days postoperatively, to evaluate post extraction healing and to validate the use of a capillary glucose monitor for glucose level assessment in oral surgery type 2 diabetic outpatients. Material and methods: Twenty type 2 diabetic patients underwent minor oral surgeries. Capillary and plasma glucose exams were taken from subjects in fasting and 2h post-prandial condition, before and after oral surgery, in four different clinical moments. Clinical characteristics of wound healing were recorded. A commercial self-monitor was used for capillary tests. Data were submitted to statistical analysis (level of significance ≤ 0.05). Results: Differences in capillary and plasma glucose level between the first visit and 30 days after oral surgery were statistically significant (p = 0.014 and p = 0.005). Differences between capillary and plasma glucose rate were between 4.48 and 6.5%. Wound healing was delayed in eight cases (40%). Conclusion: Infectious dental foci removal diminished blood glucose levels in type 2 diabetic patients. The capillary monitor showed to be adequate to assess immediate glucose level in oral surgery outpatients.

Descriptors: Tooth extraction. Glucose. Hyperglycemia. Diabetes Mellitus. Periodontitis.

RESUMO

O objetivo deste estudo foi investigar se a remoção cirúrgica de focos de infecção tem efeito sobre o controle metabólico dos níveis de glicemia após 30 dias, avaliar a reparação tecidual pós-exodontia e validar a utilização de um monitor de glicemia capilar para avaliação dos níveis de glicemia para adequação de pacientes portadores de diabetes tipo 2 para cirurgias odontológicas ambulatoriais. Materiais e métodos: Vinte pacientes portadores de diabetes tipo 2 foram submetidos a cirurgias odontológicas. Foram realizados exames de glicemia capilar e plasmática dos sujeitos em estado de jejum e em condições pós-prandial de duas horas, antes e após cirurgias odontológicas, em quatro diferentes momentos clínicos. Características clínicas do reparo tecidual também foram anotadas. Os dados foram submetidos a estudo estatístico, com nível de significância ≤ 0,05. Resultados: As diferenças entre os valores das glicemias capilar e plasmática entre a primeira visita e após 30 dias das cirurgias odontológicas foram estatisticamente significativas (p = 0,014 e p = 0,005). As diferenças entre as glicemias capilares e plasmáticas estavam entre 4,48 e 6.5%. A reparação esteve atrasada em oito casos (40%). Conclusão: A remoção de focos de infecção odontogênica diminuiu os níveis de glicemia em pacientes diabéticos do tipo 2. O monitor de glicemia capilar mostrou-se adequado para avaliar os níveis de glicemia imediatos para adequação de cirurgias odontológicas ambulatoriais.

Descritores: Extração dentária. Glucose. Hiperglicemia. Diabetes mellitus. Periodontite.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is an increasing worldwide disorder. It has been considered a major public health problem18. It was estimated that in 2010 type 2 diabetic individuals corresponded approximately to 285 millions of people. At 2030, this amount will probably arise to 439 millions. Gender, age and ethnicity are considered risk features to development of the disease2,3,18.

Diabetes is a condition characterized by hyperglycemia that impairs glucose balance. It can mainly occur as a consequence of three factors: increasing resistance of insulin, defect of insulin secretion by pancreatic β-cells or endogenous liver glucose production enhancing. Polyuria, excessive hunger, extreme thirst and unintentional weight lost are typical symptoms2,3.

Blood glucose enhance, diminishing of glucose tolerance, persistently inadequate glycemic control coupled to microvascular disturbances that lead to severe morbidity and mortality. Retinopathy, nephropathy and neuropathy are common complications of the disturb, and cardiovascular disease is the first death cause5.

It is well-known that oral health maintenance is primordial to glycemic control in diabetes. Inflammation and infection of dental origin are conditions that conduct to hyperglycemia7,23.

It has been demonstrated in this issue the importance of clinical treatment and periodontal health maintenance at the same time as glucose control measurement. It is well established that blood glucose level checking previously to oral surgery is a good clinical practice to avoid operative urgencies, like hypoglycemia distress or wound healing complications2,7,9,10,16,21,24. Literature, however, is poor about oral surgery management protocols regarding diabetic patients. The limited access of state-insured patients to oral health care brings several difficulties in basic attention for type 2 DM patients.

Objectives

The present study aimed to investigate the effects of oral infectious foci removal on metabolic glucose level control, to evaluate post extraction healing and to validate the capillary exam as an instant glucose level assessment in oral surgery type 2 diabetic outpatients.

Method and Materials

This study was carried out after the approval by the Ethical Committee in Human Research of Faculty of Dentistry of Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil, under protocol number 201/06. Subjects were selected from 3.000 patients that come to treatment (2008 and 2009) at Oral Minor Surgery Service of the Dental Clinic of the University.

The criteria for inclusion were: patients of both genders, above 40-years with type 2 DM, presenting no major diabetic complications, in use of oral hypoglycemic agents without adjuvant insulin, with no history of systemic antibiotic administration within the last three months and necessity of tooth extraction or other minor surgery for removal of at least one serious infectious focus.

Patients with diabetes diagnose earlier than six months, individuals in use of insulin associated or not with oral hypoglycemic agents, smokers, patients with severe oral infection or history of systemic infection were not included.

Twenty-five subjects fulfilled those criteria and were asked to sign the informed consent form. Patients underwent oral clinical and dental radiographic examination. Infection foci were diagnosed when it was present: chronic periodontitis and periodontal pocket above 5 mm with severe bone resorption and tooth mobility index in grade 2 or 3; large and deep carious lesion in teeth with associate periapical radioluscence suggesting periapical lesion without the possibility of conservative treatment; or presence of impacted tooth with or without associate osteolitic bone lesion.

Antibiotic prophylaxis with 2g-Amoxicillin one hour before oral surgery procedure was prescribed when purulent periodontal drainage or osteolitic lesions were presented.

At the first visit, medical evaluation and nutritional orientation were achieved to all patients. Seven days before oral surgery procedures, fasting capillary (C1) and plasma (P1) glucose were collected. A self-monitor (Accu-Chek Advantage® – Roche) was used for capillary tests. Venous blood sample was taken from each patient, and plasma glucose was processed at the Laboratory of Clinic Pathology from the University Hospital. Samples were always collected between 8 and 9 am.

In the day of surgery, two-hour post-prandial capillary (C2) and plasma (P2) glucose were collected. Patients underwent infectious foci removal by the same oral surgeon under local anesthesia and following minor surgical trauma. Before surgery, careful perioral antisepsis was performed in every patient with aqueous 0.2%-chlorexidine digluconate. Intraoral antisepsis was performed through 5 mL mouthwash of 0.12%-chlorexidine for one minute. In favor of postoperative pain relief, 750 mg-Acetaminophen were prescribed every six hours for three days to all patients.

Seven days after surgery, 2-hour post-prandial capillary (C3) and plasma (P3) glucose tests were collected. Post extraction socket were carefully examined by a unique calibrated observer. Clinical characteristics of alveolar healing delaying considered: presence of erythema, local edema, exacerbation of granulation tissue and, eventually, any other intercurrence were recorded.

After removal of infectious foci in the 30th day, the patients were clinically re-evaluated, and fasting capillary (C4) and plasma (P4) glucose tests were collected.

The patient that has teeth with conservative treatment possibility was referred to periodontics and rehabilitation treatment.

Capillary and plasma glucose tests data were submitted to statistic analysis by SPSS – 17-0 Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test, considering a significance value p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Twenty five patients were initially allocated, but five of them were not included on the study — one because he had failed on blood test procedure, one because of an untruth about non-smoking habits and three of them for giving up in the middle of the study. Twenty patients, ten women (50%) and ten men (50%) with mean age of 56-years took part as the final sample. Mean time of diabetes diagnosis was eight-years. Of patients, 100% were in use of 850 mg-metformin associated in 50% of cases to 5 mg-glibenclamide.

Sixteen patients presented arterial systemic hypertension (80%), eight informed hypercholesterolemia (40%), three reported heart disease (15%) and a very few of them informed other health problems, like hyperthyroidism labyrinthitis, bronchitis, gastritis and oral lichen planus.

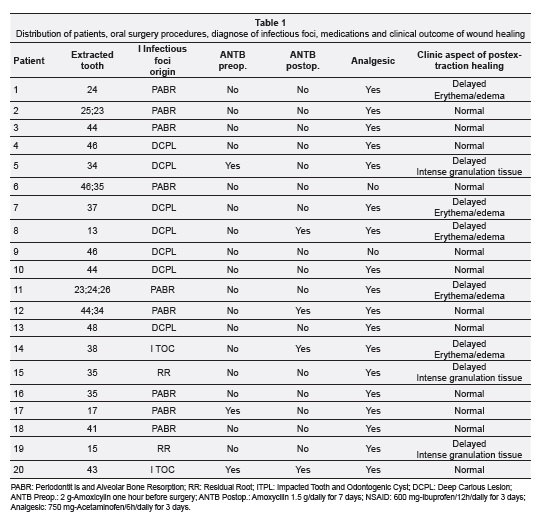

Table 1 lists patient's distribution, type of oral surgery, clinical aspects of infectious foci diagnose, pre and postoperative medications, and clinical aspects of post extraction healing.

The eight subjects that presented delayed healing were instructed to mouthwash 5 mL of 0.12%-chlorexidine solution daily for seven days. After that period, they were cautious examined, and follow-up showed that post extraction sockets healed normally.

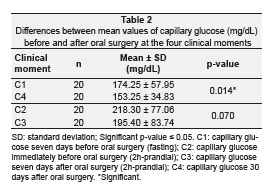

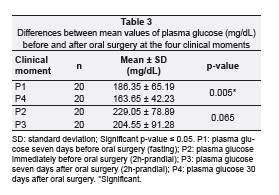

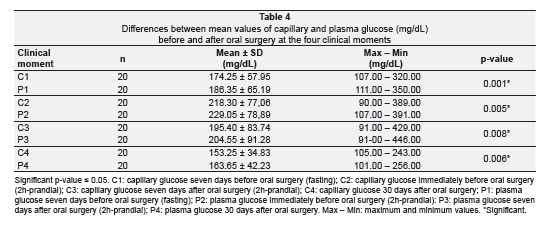

Mean glucose values, capillary (174.25 mg/dL) and plasma (186.35 mg/dL) showed hyperglycemia in the first visit. Glucose values, capillary and plasma diminished after 30 days of the first visit. Descriptive statistic of the results was demonstrated in Tables 2 and 3. Mean of capillary glucose values were constantly lower when compared to plasma glucose (Table 4).

Results showed that capillary and plasma glucose value differences were between 4.48 and 6.5%.

Discussion

Thirty days after first visit blood glucose tests, capillary and venous showed significantly lower ranges once infectious foci were removed. Individual values (data not shown), even though they were not at normal limits, were appreciably inferior to those seen in the first visit.

Severe periodontal disease was the main origin of the presented infectious foci. Periodontitis is a non specific complication of diabetes, but it is considered the sixtieth more frequent one16,19. Between 5 to 15% of diabetics patients have severe periodontal disease. It is the major cause of tooth lost in adults, causing important disturb on mastication function14. It is well known that infectious foci including periodontal pockets and dental abscess conduct to hyperglycemia. Systemically, this condition brings to insulin resistance, what enhances the cardiovascular risk5,6,8,12,14,19,20,23.

Clinical treatment of periodontitis2,7,9,16,21 is founded on mechanical control of dental plaque which includes generally adequate oral hygiene techniques instruction, basic procedures of full-mouth scaling and root planning. Surgical periodontal management approach and eventually antibiotic therapy complete the treatment. Follow-up and maintenance of severe and mild cases should be performed at short time intervals, in two or three month, as an attempt to avoid tooth extraction25.

Even with a strict metabolic control, some authors12,14,19,20,22 observed that diabetes condition have a progressive tendency to periodontal destruction. Deficient metabolic control and consequent hyperglycemia sustenance contribute to a considerable increase on oral infections susceptibility.

Literature has shown that periodontal treatment influences glucose control. Tooth avulsion may sound an extreme management procedure; nevertheless, in developing countries, the limited access to health care system and inconstancies on periodontal therapy are a reality. It is rare to find studies associating oral surgery, glucose tests evaluation and post extraction healing and glucose control.

Spontaneous entrance of patients at the Dental Clinic of the University and the strict inclusion criteria can justify the sample (n = 20). Some other investigations have used similar sampling although inclusion and exclusion criteria for diabetics subjects were different7,12,16,17,21,22,24 Many patients could not be included in our sample because they were smokers and/or in use of insulin associated to oral hypoglycemic agent.

Some variables could partially explain the non significant differences founded at second (C2, P2) and third (C3, P3) blood samples (Table 2 and 3). Oral surgeries were performed in non-fasting outpatients under local anesthesia. Furthermore, the acute psychological stress on the day of surgery and the inflammatory process during tissue repair seven days after operation could possibly have maintained the hyperglycemia state.

The capillary glucose monitor showed to be accurate. Although differences between capillary and plasma glucose values have been significant (Table 4), they were at the expected American Diabetes Association range, i.e. between ± 5.5% to ± 15%4.

Capillary glucose test is a simple, sensible and quick method to achieve instant glucose level in clinical practice. It is popular at US since 1978, and current commercial monitors have shown 50 to 60% sensibility and 90% of specificity4,11.

We must emphasize that the self-monitor is not appropriate for diabetes diagnose6,25. On the other hand, its use should be encouraged for immediate conduct to check glucose level and to prevent hypoglycemia distress.

The positive results in reducing hyperglycemia in this study certainly were influenced by the health care and diet instructions given to patients at the beginning of the research. The great majority of chronically illness individuals are refractory to follow medical orientations. Multi professional interaction by endocrinologists, dentists, oral surgeons and nutritionists is very important in diminishing risk factors in diabetes patients19,20,24.

It was observed that blood glucose diminished after 30 days of odontogenic infections foci elimination even though values have been above normal limits. Other authors7,9,16,21,24,26 presented significant decrease of blood glucose level after four weeks of non-surgical periodontal treatment nevertheless results were also above normal level.

Prophylactic antibiotic was not a routine measure, and wound healing occurred normally in 60% of cases. The sample of this study did not permit to correlate the use of antibiotics, pre or postoperatively, and the improvement in wound healing. Although literature does not have consent about antimicrobial protocol2 for oral surgery diabetic patients, we suggest that antibiotic prescription must be based on periodontal disease status, on oral surgery difficulties and on patient's systemic condition. Irrational use of antibiotic drugs can lead to bacterial resistance or to important intercurrences, like acute hyper sensibility, drug intolerance or adverse effects2,15.

There is no agreement for the upper limited blood glucose level when oral surgery procedures could be done in uncontrolled diabetic patients2,16,19. In this research, glucose highest range was above 300 mg/dL in some patients before oral surgery procedures. Some kind of wound healing impediment occurred in 40% of the subjects. However, it was not possible to correlate the uppermost glucose level observed (429.00 – 446.00 mg/dL) and the delay in post extraction alveolar healing. Probably, local surgical trauma, time of operation and whole mouth periodontal condition have influenced.

A recent research1 showed no difference in post extraction epithelialization or healing in poorly controlled diabetic patients compared to well-controlled ones. Authors could not either correlate healing and capillary blood glucose level or glycosylated hemoglobin and evolution of patient's disease1.

More prospective studies may be carry out to associate oral surgery, therapeutic dose and time of delivery of antibiotics and glucose control for a long period employing glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) as a parameter. HbA1c is a gold standard exam to verify hypoglycemic therapeutic efficacy13,15,19,26 and is precisely to indicate if the patient is controlling the disease during three months.

In summary, the results showed that infectious foci removal reduced hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetic patients. Oral surgery practiced through minor trauma and taking care of aseptic and antiseptic conditions are important factors that direct wound healing to occur without disturbances. The tested monitor showed to be useful, practical, sensible and precise in assessing glucose immediate condition on type 2 diabetic patients.

Acknowledgments

Rosemary Aparecida Fracoli Pécora, Aparecida Conceição de Souza and Juliana Bannwart de Andrade Machado for technical and laboratory assistance.

Bibliographic References

1. Aronovich S, Skope LW, Kelly JPW, Kyriakides TC. The relationship of glycemic control to the outcomes of dental extractions. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2010;68(12):2955-61. [ Links ]

2. Barasch A, Safford MM, Litaker MS, Gilbert GH. Risk factors for oral postoperative infection in patients with diabetes. Spec Care Dent 2008;28(4):159-66. [ Links ]

3. Bergman SA. Perioperative management of the diabetic patient. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2007;103(6):731-7. [ Links ]

4. Blake DR, Nathan DM. Point-of-care testing for diabetes. Crit Care Nurs Q 2004;27(2):150-61. [ Links ]

5. Coursin DB, Connery LE, Ketzler JT. Perioperative diabetic and hyperglycemic management issues. Crit Care Med 2004;32(4):S116-25 [ Links ]

6. Janket SJ, Jones JA, Meurman JH, Baird AE, Van Dyke TE. Oral infection, hyperglycemia, and endothelial dysfunction. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2008;105(2):173-9. [ Links ]

7. Janket SJ, Wightman A, Baird AE, Van Dyke TE, Jones JA. Does periodontal treatment improve glycemic control in diabetic patients? A meta-analysis of intervention studies. J Dent Res 2005;84(12):1154-9. [ Links ]

8. Kim J, Amar S. Periodontal disease and systemic conditions: a bidirectional relationship. Odontology 2006;94(1):10-21. [ Links ]

9. Kiran M, Arpak N, Ünsal E, Erdoğan MF. The effect of improved periodontal health on metabolic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Periodontol 2005;32(2):266-72. [ Links ]

10. Lamster IB, Lalla E, Borgnakke WS, Taylor GW. The relationship between oral health and diabetes mellitus. J Am Dent Assoc 2008;139(Suppl):S19-24 [ Links ]

11. LeRoith D, Smith DO. Monitoring glycemic control: The cornerstone of diabetes care. Clin Ther 2005;27(10):1489-99. [ Links ]

12. Manfredi M, McCullough MJ, Vescosi P, Al-Kaarawi ZM, Poter SR. Update on diabetes mellitus and related oral diseases. Oral Dis 2004;10(4):187-200. [ Links ]

13. Mealey BL, Oates TW. Diabetes mellitus and periodontal diseases. J Periodontol 2006;77(8):1289-303. [ Links ]

14. Nagasawa T, Noda M, Katagiri S, Takaichi M, Takahashi Y, Wara-Aswapati N, et al. Relationship between periodontitis and diabetes – importance of a clinical study to prove the vicious cycle. Intern Med 2010;49(10):881-5.

15. Rees TD. Periodontal management of the patient with diabetes mellitus. Periodontol 2000 2000;23:63-72. [ Links ]

16. Rehman HU, Mohammed K. Perioperative management of diabetic patients. Curr Surg 2003;60(6):607-11. [ Links ]

17. Rodrigues DC, Taba MJ, Novaes AB, Souza SL, Grisi MF. Effect of non-surgical periodontal therapy on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Periodontol 2003;74(9):1361-7. [ Links ]

18. Saudek CD, Derr RL, Kalyani RR. Assessing glycemia in diabetes using self-monitoring blood glucose and hemoglobin A1c. JAMA 2006;295(14):1688-97. [ Links ]

19. Shaw JE, Sicree RA, Zimmet PZ. Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2010;87(1):4-14. [ Links ]

20. Skamagas M, Breen TL, LeRoith D. Update on diabetes mellitus: prevention, treatment, and association with oral diseases. Oral Dis 2008;14(2):105-14. [ Links ]

21. Southerland JH, Taylor GW, Offenbacher S. Diabetes and periodontal infection: Making the connection. Clin Diabetes 2005;23:171-8. [ Links ]

22. Stewart JE, Wager KA, Friedlander AH, Zadeh HH. The effect of periodontal treatment on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Periodontol 2001;28(4):306-10. [ Links ]

23. Taylor GW, Borgnakke WS. Periodontal disease: associations with diabetes, glycemic control and complications. Oral Dis 2008;14(3):191-203. [ Links ]

24. Taylor GW. Periodontal treatment and its effects on glycemic control. A review of the evidence. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1999;87(3):311-6. [ Links ]

25. Taylor GW. The effects of periodontal treatment on diabetes. J Am Dent Assoc 2003;134:41S-8. [ Links ]

26. Vernillo AT. Diabetes mellitus: Relevance to dental treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2001;91(3):263-70. [ Links ]

Endereço para correspondência:

Endereço para correspondência:

Maria Cristina Zindel Deboni

Avenida Prof. Lineu Prestes, 2227 – Cidade Universitária, Butantã

Zip Code 05508-000 – São Paulo/SP, Brazil

e-mail: mczdebon@usp.br

Received in: 3/16/12

Accepted in: 8/25/12