Brazilian Journal of Oral Sciences

ISSN 1677-3225

Braz. J. Oral Sci. vol.11 no.1 Piracicaba ene./mar. 2012

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Trends in dental caries experience and fluorosis prevalence in 12-year-old Brazilian schoolchildren from two different towns

Aline Sampiere Tonello BenazziI; Renato Pereira da SilvaII; Marcelo de Castro MeneghimIII; Antonio Carlos PereiraIII; Glaucia Maria Bovi AmbrosanoIII

IPhD, Department of Community Dentistry, Piracicaba Dental School, University of Campinas, Brazil

IIGraduate Student of Program in Dentistry, Department of Community Dentistry, Piracicaba Dental School, University of Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil

IIIProfessor, Department of Community Dentistry, Piracicaba Dental School, University of Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil

ABSTRACT

AIM: To describe the prevalence of dental caries and fluorosis in schoolchildren from two different towns in São Paulo State, Brazil, 2007 - town A (water fluoridation since 1971) and town B (water fluoridation since 1997) - and to compare current prevalence rates with previous surveys, in town A, for dental caries (1971-2005) and for dental fluorosis (1991-2001), and in town B, for dental caries and dental fluorosis (1991-2004).

METHODS: The sample consisted of 724 schoolchildren aged 12 years from public and private schools (town A) and 197 schoolchildren from public schools (town B). The schoolchildren were examined under natural light by a dentist, using CPI probes and oral mirrors. The mean number of decayed, missing and filled permanent teeth (DMFT), and Significant Caries (SiC) Index were determined for dental caries and the Thylstrup and Fejerskov index (T-F) for fluorosis.

RESULTS: The DMFT was 0.85 and 1.02; SiC index was 2.52 and 2.83 in towns A and B, respectively. Fluorosis prevalence was 29.4% (town A) and 25.4% (town B). In both towns, a significant dental caries reduction has been observed. Concerning fluorosis prevalence, an increase of 44.1% was noted in town A and 1170% in town B.

CONCLUSIONS: Results show continuous decrease in dental caries experience in both towns. Regarding fluorosis prevalence, stabilization trends were observed in town A. In town B, however, a constant increase was noted.

Keywords: dental caries, fluorosis, DMF index, oral health, epidemiology.

Introduction

Trends in caries experience have been reported throughout the world1-4. Caries decline has been also observed in Brazil in both fluoridated and non-fluoridated areas, mainly in schoolchildren in the southern and southeastern regions5-6. The most recent epidemiological survey of oral health promoted by the Ministry of Health confirmed the trend of decline of caries in Brazilian schoolchildren7. Although, a series of clinical consequences have been observed over the last decades, such as the reduction in disease progression speed8, and the polarization phenomenon in which a minority of individuals presents the highest caries scores9-11. The minority of individuals, the so-called high-caries risk individuals12, usually belongs to a family with low monthly income13.

On other hand, an increase of fluorosis prevalence has also been observed throughout the world14-15. Some findings suggest that risk of fluorosis development is associated with regular use of fluoride supplements16-17. Despite of the use of fluoride toothpaste by young children can be considered a risk factor for dental fluorosis18, a recent review of the literature showed that the evidence pointing to the conclusion that starting the use of fluoride toothpaste in children under 12 months of age may be associated with an increased risk of fluorosis is weak and unreliable, and, even for older children, the evidence is equivocal19.

Although the present study is regarded as a local epidemiological survey, it presents 36 years of longitudinal data. Taking into account all these factors, it is essential that studies are carried out to monitor these tendencies and plan actions for public oral health. The aims of this research were to describe the prevalence of dental caries and dental fluorosis in 12-year-old schoolchildren from two different towns in São Paulo State, Brazil, 2007 - town A (water fluoridation since 1971) and town B (water fluoridation since 1997) - and to compare the current prevalence rates with those from previous surveys, developed in town A (1971-2005), for dental caries and for dental fluorosis (1991-2001), and in town B, for dental caries and dental fluorosis (1991-2004).

Material and methods

Ethical aspects

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Piracicaba Dental School, University of Campinas, protocol number 089/2006.

Characteristics of the towns

Both towns are located in the São Paulo State, Brazil. Town A has 358,108 inhabitants20. Fluoride has been added to water supply since 1971 (0.7 ppmF). Town B has 18,026 inhabitants20. Fluoride has been added to water supply since 1997 (0.7 ppm F).

Population studied

In town A, the sample size was calculated on the basis of caries experience reported in previous studies. A cluster sampling method was used admitting a sampling error of 0.2, mean number of decayed, missing and filled permanent teeth (DMFT) and, design error of 2, mean of 1.32 DMFT, standard deviation (SD) of 1.92, non-reply rate (loss of sampling elements) of 20%, and confidence level of 95%, 850 schoolchildren aged 12 years were selected in 2007. Public and private schools were randomly selected. Thus, 18 public and 6 private schools were selected, totalizing 24 schools, and 12 year-old children were chosen at random in each school (n=850). The inclusion criteria were: children whose parents had given consent for participation, were present on the examination day, did not present severe dental hypoplasia, and did not use fixed orthodontic appliance. The final sample in 2007 was composed of 724 12-year-old schoolchildren of both genders, out of which, 613 were from public schools and 111 from private schools, achieving a response rate of 85%.

In town B, considering that exist only three public schools, all 12-year-old schoolchildren, were invited to participate in this study, totalizing 244 children. The inclusion criteria were the same for town A. The final sample in 2007 was composed of 197 12-year-old schoolchildren, achieving a response rate of 80.7%.

Diagnostic criteria and codes

Dental caries was registered using the DMFT index according to World Health Organization caries diagnostic criteria21 and the Significant Caries (SiC) index that was determined for the onethird of the sample with the highest caries scores22. Fluorosis prevalence was measured by the T-F index23.

Calibration

A benchmark dental examiner, skilled in epidemiological surveys, conducted the calibration process in 2007. In the practical activities with clinical examinations and data analyzes, the mean Kappa was 0.89 for dental caries and 0.88 for dental fluorosis. Approximately 10% of the sample was re-examined in order to verify the intra-examiner reproducibility. Kappa values of 0.95 for dental caries and 0.89 Kappa for dental fluorosis were observed.

Examination methodology

The results of the present study were compared with the results of previous surveys carried out in town A, (1971- 2005) for dental caries and (1991-2001) for dental fluorosis, and in town B (1991-2004), for dental caries and dental fluorosis. All epidemiological surveys reported for both towns were conducted following the same protocol. Epidemiological exams in this study were carried out in 2007, and performed by one previously calibrated dentist in outdoor setting, under natural light, using CPI probes and mirrors #521. Before examination each child brushed their teeth under the supervision of a dental hygienist.

Statistical procedures

The DMFT and SiC indexes, the proportion of cariesfree children and the percentage of children with dental fluorosis were calculated. The variation of DMFT index over time was assessed by analysis of regression, and fluorosis prevalence was compared over time by the Chi-square test at 5% significance level.

Results

In 2007, the mean value of DMFT and SiC index were 0.85 (SD=1.54) and 2.52 (SD = 1.72), respectively, in town A and 1.02 (SD=1.61) and 2.83 (SD=1.60), respectively, in town B. The results show that 65.61% and 59.39% of children were caries-free for town A and town B, respectively.

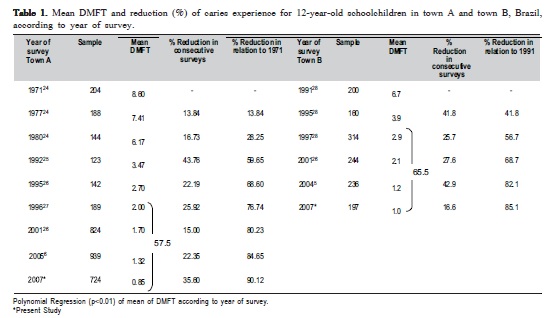

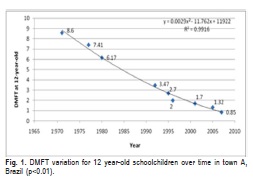

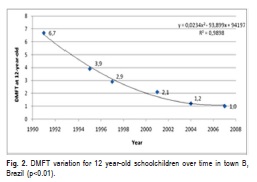

Table 1 summarizes the results of dental caries experience obtained in all surveys in both towns. In town A, the studies carried out between 1971 and 2007 and showed a reduction of 90.12% in the DMFT index, out of which 57.5% was in the last 11 years, in the 1996-2007 period. In town B, the six surveys carried out between 1991 and 2007, showed a reduction of 85.1% in the DMFT index. After 10 years of fluoridation of the water supply (1997-2007), caries experience decreased by 65.5%, while in the 1991-1997 period, with no fluoride in drinking water, the percentage of caries reduction was 56.7%.

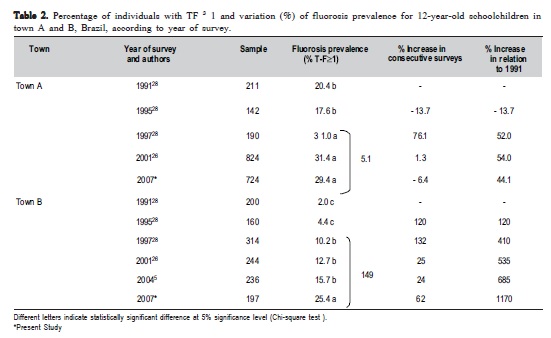

Table 2 shows the prevalence of fluorosis (T-F ³ 1) in both towns between 1991 and 2007. In town A, 29.4% of the individuals presented fluorosis. A total of 70.6%, 13.95%, 14.78% and 0.67% of the children were scored as T-F=0, TF= 1, T-F=2 and T-F=3, respectively, in 2007. According to the data collected in 1991, out of the 211 children examined, 20.4% presented fluorosis, result that remained nearly the same when data was collected in 1995, when 17.6% presented the same condition, not showing significant difference (p<0.05). In the 1997-2001 period, the increase was only 5.1%, not showing significant difference either (p<0.05). When comparing the data collected in 1991 and in 2007, a 44.1% increase of fluorosis prevalence was observed.

In town B, between 1991 and 2007, an increase of 1170% of fluorosis prevalence was noted. In 2007, 25.4% of the sample presented fluorosis (Table 2). A total of 74.6% of the schoolchildren were fluorosis free (T-F=0), and 7.64%, 16.25% and 1.51% of the sample presented fluorosis T-F=1, T-F=2 and T-F=3, respectively.

A significant decline of DMFT in the 12-year-old schoolchildren could be demonstrated over a 36-year period of evaluation by analysis of regression with R2 = 0.9916, (p<0.01) for of town A and over a 16-year-period of evaluation by analysis of regression with R2 = 0.9898 for town B, showing linear effect for DMFT and year of survey (Figures 1 and 2).

Discussion

Results show constant decrease in caries prevalence in both towns over time (Figures 1 and 2). The decline in caries prevalence detected in the present study is an event also observed worldwide29. In comparison to national data30, 12- year-old schoolchildren from town A and B presented lower caries experience (0.85 and 1.0 DMFT respectively). Recent international reported data have shown that the DMFT for 12-year-old children is also low ranging from 0.80 in Dublin, Ireland31. However, higher results were observed in a survey conducted with non-indigenous schoolchildren living in the Amazon basin of Ecuador, showing a DMFT of 5.2532.

In town A, taking into account caries prevalence in studies carried out in 1980, DMFT was found to be nearly three times higher than the one found in 1992, which lead us to infer that schoolchildren examined in this last year benefited from fluoridated water, other forms of caries control and prevention, which may have caused this reduction. Even though the experimental design of the present study did not supply data for the evaluation of the causes for this reduction, one can conclude that the wide use of dentifrice fluoridated, which became available in Brazil in 1989, interacted in such a way that promoted a decline in caries prevalence.

As for the SiC index, 2.52 and 2.83 were found in town A and B in 2007, respectively. These values are over two times higher than the mean DMFT for the entire sample in both towns. These findings are in line with some studies reported33, demonstrating that caries experience in those individuals more affected by the disease is over two times higher34.

Regarding dental fluorosis, reports in scientific literature have demonstrated an increase in prevalence rates35-36, which could be confirmed in this research in town B, when comparing data from 2007 with those from 1991 to 2004 (Table 2). However, in town A, results show that this index remained nearly the same for 10 years (1997 to 2007), presenting a tendency to stabilize in most part of the period, showing a small reduction of 6.4% between 2001 and 2007, without statistical significance (p<0.05).

Considering the increase of fluorosis prevalence comparing both towns from 1997 (year that began the process of water fluoridation in town B) to 2007, it was observed that town A presented an increase of only 5.1%, whereas in town B, the increase was 149%. One can suggest that others studies could be carried out to monitor fluorosis prevalence in town B.

In relation to fluorosis severity, the lowest score for both towns was the component T-F 3, and the highest was the TF 2. However, in a research carried out in Nigeria, the most severe form was T-F 6 and T-F 537.

According to the epidemiological surveys discussed in this study, a continuous decline of dental caries experience could be verified after 36 years of water supply fluoridation in town A, from 1971 to 2007, and in town B from 1991 to 2007. Regarding dental fluorosis, stabilization trends were observed in town A. However, in town B, a constant increase was noted. It is possible that concomitant use of fluoridated dentifrice and water are directly related with the increase inthe prevalence of dental fluorosis. Future epidemiological surveys should be carried out to evaluate and monitor dental caries and fluorosis trends over time.

Acknowledgements

The authors would to acknowledge the financial support of the FAPESP (grants #06/50788-0 and #06/58881-9). We also give special thanks to the Principals of the schools and all the children, who contributed to the accomplishment of the survey.

References

1. Pieper K, Schulte AG. The decline in dental caries among 12-year-old children in Germany between 1994 and 2000. Community Dent Health. 2004; 213: 199-206. [ Links ]

2. Tagliaferro EPS, Meneghim MC, Ambrosano GMB, Pereira AC, Sales-Peres SHC, Sales-Peres A, et al. Distribution and prevalence of dental caries in Bauru, Brazil, 1976-2006. Int Dent J. 2008; 58: 75-80. [ Links ]

3. Parker EJ, Jamieson LM, Broughton J, Albino J, Lawrence HP, Thomson KR. The oral health of Indigenous children: A review of four nations. J Paediatr Child Health. 2010; 46: 483-6. [ Links ]

4. Micheelis W. Oral health in Germany: an oral epidemiological outline. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2011; 54: 1022-6. [ Links ]

5. Meneghim MC, Tagliaferro EPS, Tengan C, Pedroso ZMA, Pereira AC, Ambrosano GMB, et al. Trends in caries experience and fluorosis prevalence in 11- to 12-year-old Brazilian Children between 1991 and 2004. Oral Health Prevent Dent. 2006; 4: 193-8. [ Links ]

6. Pereira SM, Tagliaferro EPS, Ambrosano GMB, Cortellazzi KL, Meneghim MC, Pereira AC. Dental Caries in 12-year-old Schoolchildren and its relationship with socioeconomic and behavioral variables. Oral Health Prevent Dent. 2007; 5: 299-306. [ Links ]

7. Brazil. Health Ministry of Brazil. SB Brazil 2010 Project: National oral health research, 2010. Brasília: Health Ministry Ministério da Saúde. Available from: http://www.sbbrasil2010.org. [ Links ]

8. Moberg Skold U, Birkhed D, Borg E, Petersson LG. Approximal caries development in adolescents with low to moderate caries risk after different 3-year school-based supervised fluoride mouth rinsing programmes. Caries Res. 2005; 39: 529-35. [ Links ]

9. Narvai PC, Frazão P, Roncalli AG, Antunes, JLF. Dental caries in Brazil: decline, polarization, inequality and social exclusion. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2006; 19: 385-393. [ Links ]

10. Namal N, Can G, Vehid S, Koksal S, Kaypmaz A. Dental health status and risk factors for dental caries in adults in Istanbul, Turkey. East Mediterr Health J. 2008; 14: 110-8. [ Links ]

11. Ditmyer M, Dounis G, Mobley C, Schwarz E. A case-control study of determinants for high and low dental caries prevalence in Nevada youth. BMC Oral Health. 2010; 10: 1- 8. [ Links ]

12. Tagliaferro EPS, Ambrosano GMB, Meneghim MC, Pereira AC. Risk indicators and risk prediction of dental caries in schoolchildren. J Appl Oral Sci. 2008; 16: 408-13. [ Links ]

13. Piovesan C, Mendes FM, Antunes, JLF, Ardenghi TM. Inequalities in the distribution of dental caries among 12-year-old Brazilian schoolchildren. Braz Oral Res. 2011; 25: 69-75. [ Links ]

14. Kukleva MP, Kondeva VK, Isheva AV, Rimalovska SI. Comparative study of dental caries and dental fluorosis in populations of different dental fluorosis prevalence. Folia Med (Plovdiv). 2009; 51: 45-52. [ Links ]

15. Anuradha B, Laxmi GS, Sudhakar P, Malik V, Reddy KA, Reddy SN, et al. Prevalence of Dental Caries among 13 and 15-Year-Old School Children in an Endemic Fluorosis Area: A Cross-sectional Study. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2011; 12: 447-50. [ Links ]

16. Pendrys DG, Haugejorden O, Bårdsen A, Wang NJ, Gustavsen, F. The risk of enamel fluorosis and caries among Norwegian children: implications for Norway and the United States. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010; 141: 401-4. [ Links ]

17. Levy SM, Broffitt B, Marschall TA, Eichenberger-Gilmore JM, Warren JJ. Associations between fluorosis of permanent incisors and fluoride intake from infant formula, other dietary sources and dentifrice during early childhood. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010; 141: 1190-1201. [ Links ]

18. Mascarenhas AK. Risk factors for dental fluorosis: a review of the recent literature. Pediatr Dent. 2000; 22: 269-77. [ Links ]

19. Wong MC, Glenny AM, Tsang BW, Lo EC, Worthington HV, Marinho VC. Topical fluoride as a cause of dental fluorosis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010; 20: CD007693. [ Links ]

20. Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics: IBGE. [cited 2009]. Available from: http: //www.ibge.gov.br/cidadesat. [ Links ]

21. World Health organization: Oral health surveys - basic methods. 4th ed. Geneva: WHO; 1997. p.66. [ Links ]

22. Bratthall D. Introducing the Significant Caries Index together with a proposal for a new global oral health goal for 12-yearolds. Int Dent J. 2000; 50: 378-84. [ Links ]

23. Thylstrup A, Fejerskov O. Clinical appearance of dental fluorosis in permanent teeth in relation to histologic changes. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1978; 6: 315-28. [ Links ]

24. Moreira BHW, Tuma AJ, Guimarães LO. Incidence of dental caries in students of Piracicaba, SP after 6 and 9 years of water supply fluoridation. Rev Bras Odontol. 1983; 40: 11-4. [ Links ]

25. Pereira AC, Biscaro SL, Moreira BHW. Oral conditions of 7–12-year-old schoolchildren, after 20 years of fluoridation of the public water supply in Piracicaba. Rev Paul Odontol. 1995; 17: 30-6.

26. Kozlowski FC. Prevalence and severity of fluorosis and dental caries related to socioeconomic factors [thesis]. Piracicaba (SP): School of Dentistry, State University of Campinas –UNICAMP; 2001.

27. Basting RT, Pereira AC, Meneghim MC. Evaluation of dental caries prevalence in students from Piracicaba, SP, Brazil, after 25 years of fluoridation of the public water supply. Rev Odontol Univ Sao Paulo. 1997; 11: 287-92. [ Links ]

28. Pereira AC, Mialhe FL, Bianchini FLC, Meneghim MC. Prevalence of dental caries and dental fluorosis in schoolchildren of towns with different fluoride concentrations in water supply. Rev Bras Odontol Saude Colet 2001; 2: 34-9. [ Links ]

29. Campus G, Sacco G, Cagetti M, Abati S. Changing trend of caries from 1989 to 2004 among 12-year old Sardinian children. Biomed Central Public Health. 2007; 7: 1-6. [ Links ]

30. Brazil. Health Ministry of Brazil. SB Brasil 2003 Project - Oral health conditions of the Brazilian population 2002-2003. National Division of Oral Health. Brasília: Health Ministry; 2004. [ Links ]

31. Sagheri D, McLoughlin J, Clarkson JJ. The prevalence of dental caries and fissure sealants in 12 year old children by disadvantaged status in Dublin (Ireland). Community Dent Health. 2009; 26: 32-7. [ Links ]

32. Medina W, Hurtig AK, San Sebastián M, Quizhpe E, Romero C. Dental Caries in 6-12-Year-Old Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Schoolchildren in the Amazon Basin of Ecuador. Braz Dent J. 2008; 19: 83-6. [ Links ]

33. Ditmyer M, Dounis G, Mobley C, Schwarz E. Inequalities of caries experience in Nevada youth expressed by DMFT index vs. Significant Caries Index (SiC) over time. BMC Oral Health. 2011;11: 12. [ Links ]

34. Marthaler T, Menghini G, Steiner M. Use of the Significant Caries Index in quantifying the changes in caries in Switzerland from 1964 to 2000. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005; 33: 159-66. [ Links ]

35. Browne D, Whelton H, O'Mullane D. Fluoride metabolism and fluorosis. J Dent. 2005; 33: 177-86. [ Links ]

36. Buzalaf MA, Levy SM. Fluoride intake of children: considerations for dental caries and dental fluorosis. Monogr Oral Sci. 2011; 22: 1-19. [ Links ]

37. Akosu TJ, Zoakah AI, Chirdan OA. The prevalence and severity of dental fluorosis in the high and low altitude parts of Central Plateau, Nigeria. Community Dent Health. 2009; 26: 138-42. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Marcelo de Castro Meneghim

Departamento de Odontologia Social,

Faculdade de Odontologia de Piracicaba,

Universidade Estadual de Campinas

Av. Limeira 901, CEP: 13414-903,

Piracicaba, SP, Brasil

E-mail: meneghim@fop.unicamp.br

Received for publication: August 23, 2011

Accepted: February 28, 2012