Services on Demand

Article

Related links

Share

Brazilian Journal of Oral Sciences

On-line version ISSN 1677-3225

Braz. J. Oral Sci. vol.11 n.4 Piracicaba Oct./Dec. 2012

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Dentistry for babies: caries experience vs. assiduity in clinical care

Letícia Vargas Freire Martins LemosI; Terezinha Esteves de Jesus BarataII; Silvio Issáo MyakiIII; Luiz Reynaldo de Figueiredo WalterIV

IDDS, MS, PhD student, Department of Pediatric Dentistry, Araraquara Dental School, UNESP – Univ Estadual Paulista, Araraquara, SP, Brazil

IIDDS, MS, PhD, Professor, Department of Preventive Dentistry and Oral Rehabilitation, Dental School, Federal University of Goiás (UFG), Goiânia, GO, BrazilIIIDDS, MS, PhD, Professor, Department of Pediatric and Social Dentistry, São José dos Campos Dental School, UNESP – Univ Estadual Paulista,

São José dos Campos, SP, Brazil

IVDDS, MS, PhD, Full Professor, Department of Pediatric Dentistry, Dental School, State University of Londrina (UEL), Londrina, PR, Brazil

ABSTRACT

AIM: This study analyzed and compared the experience of dental caries in 300 children aged 0 to 48 months, who were participants and non-participants of a preventive program 'Dentistry for babies', as well as the correlation between assiduity of dental visits and experience of dental caries.

METHODS: The subjects were randomly selected and divided into two groups: G1 'Non participant children of the Program' (n=100) and G2 'Participant Children of the Program' (n=200). Each group was subdivided in two subgroups: 0-24 months and 25-48 months. The collected data from G2 were analyzed, relating the variation of the dmft index (dmft refers to primary teeth: d = decayed, m = missing/extracted due to caries, f = filled, t = teeth) (C) and dental caries prevalence (P) with the influence of assiduity factor in each subgroup. To collect data, clinical examinations were performed using tactile and visual criteria by a single calibrated examiner. The data were statistically analyzed using the 'paired t-test', 'Mann-Whitney' and 'Chi-Squared' tests (p<0.05).

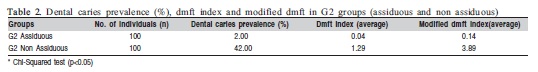

RESULTS: It was found that prevalence and dmft index were statistically significant (P=0.0001) with the greatest values observed in G1 (p=0.0001). The values were: PG1 (73%), PG2 (22%), CG1 (3.45±3.84), CG2 (0.66±1.57). Assiduity was significant in G2 (p=0.0001). The values observed were: P-Assiduous (2%), P-Non-assiduous (42%), C-Assiduous (0.04±0.31), and C-Non-assiduous (1.29±2.01).

CONCLUSIONS: The participation in the program had a positive influence on the oral health of babies. Complete assiduity to the program resulted in the lowest rates and prevalence of dental caries.

Keywords: pediatric dentistry, dental caries, epidemiology, referral and consultation, dental care.

Introduction

Early childhood caries (ECC) are to be considered any stage of caries lesion in any surface of primary teeth in babies and pre-school children up to 71 months of age1 in which there is an association with feeding before sleeping, sugar intake and inadequate hygiene2. As the development of caries is a dynamic process3, evaluation at every dental visit is necessary4-5. Assiduity to the oral health program means that the families attended regularly the program, being diligent in compliance with the instructions of the program.

The Brazilian Public Health Department provided information about theprevalence of dental caries6, which reveals that almost 27% children aged 18-36 month have at least one primary carious tooth. At the age of five, the rate of children with carious teeth reaches almost 60%6. Thus, the ECC being considered a significant public health problem3,6-7.

According to the study of Walter and Nakama8, the peak time for dental caries prevalence occurs in early childhood between the 13th-24th months. Therefore, the ideal age to start preventive dental care is before the 12th month8.

The inclusion of the initial stages of caries in epidemiological surveys is important because of the possibility of lesion reversal. Its identification is socially relevant, as it allows for early intervention9-10.

Fraiz and Walter11 evaluated 200 children, aged 24 to 48 months, who participated in a preventive oral health program for babies for at least 12 months. The population studied presented a low prevalence of dental caries. The results showed that this program positively influenced oral health of those children11.

In order to diminish the ECC index, an oral health program tailored for babies named 'Baby Clinic' was created in 1996 in Jacareí, SP, Brazil. The city has a fluoridated water supply (0.7 ppm) since 198112. 'Baby Clinic' focuses on health promotion. It was organized to educate the population to seek for oral health assistance in the first year of a baby's life. Later, parents and family were invited to attend speeches and individual dental visits to motivate them to learn the preventive measures and to carry out the preventive treatment in the clinic and at home. A great obstacle to the success of the oral health program for babies was the lack of commitment with the program4,13-14.

Compliance with the preventive/educational program is a determinant factor for success15. However, it is affected by factors such as level of satisfaction, motivation and results expected by the individuals2. In order to obtain effective health promotion and prevention of oral health diseases, it is essential to be assiduous to the program16.

After 13 years of the implementation of the Baby Clinic in Jacareí, Brazil, a pilot study showed an important decrease in dental caries in the children who participated on the program 'Dentistry for babies'16.

The goals of this study was to analyze and compare the experience of dental caries in 300 children aged 0 to 48 months, who were participants and non-participants of a preventive program 'Dentistry for babies', as well as the correlation between assiduity of dental visits and experience of dental caries. Based on the facts reported, the hypothesis of the present study was that participation in the preventive program 'Dentistry for babies' positively affects the oral health of children between the ages of 0 to 48 months, and assiduity to dental visits positively impacts the oral health of the participants of this program.

Material and methods

A cross-sectional observational study was carried out at a public health facility in the city of Jacareí, SP, Brazil. Parent consent was obtained prior to each survey. The study was approved by the Ethics in Research Committee of the São José dos Campos Dental School – UNESP (#088/2007).

Three hundred Brazilian children participated of the study. All participants were in good health. They were randomly divided into two groups, G1, named 'Nonparticipant babies of the program' (n=100), children that have never participated in preventive oral health program and G2, 'Babies of the program' (n=200), children who received early oral health care in preventive program for

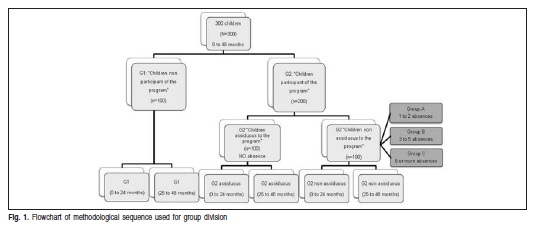

babies. Both groups (G1 and G2) were divided into two age groups between 0 and 24 months and between 25 and 48 months (Figure 1).

Assiduity to the program was considered in which the families attended the program regularly, and were diligent in compliance with the instructions. So, babies assiduous to the program are the ones who attended the recalls and had no absences. Non-assiduous babies had at least one absence.

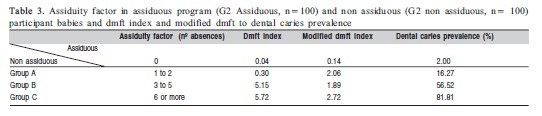

To analyze the influence of assiduity in dental caries prevalence and the dmft index (dmft refers to primary teeth: d = decayed, m = missing/extracted due to caries, f = filled, t = teeth) and modified dmft index (considering white spots) in the Oral Health Program for Babies, we analyzed all the babies of the program, aged between 0 and 48 months (G2, n=200) (Figure 1). In addition, G2 Non-assiduous (n=100) was subdivided according to the number of absences to the recalls: G2-A: 1 to 2 absences, G2-B: 3 to 5 absences and G2-C: 6 or more absences (Table 3).

Children of group G2 received routine dental visits, in compliance with the program: orientation on oral hygiene and education about feeding habits, professional cleaning with pumice cup and topical application of 5% sodium fluoride varnish, according to the patient's caries risk13. It is the protocol used in Oral Health Program for Babies.

The eligibility criteria for this study were: Inclusion criteria'! children (0 to 48 months) with no distinction of gender or ethnicity. Group G1: those who never participated in any oral health programs and, for G2: those who participated in the program for at least three months and had at least the maxillary and mandibular central incisors present in the oral cavity. Exclusion criteria'! presence of systemic disease, and/or syndromes leading to stained dental enamel. Eligible children were randomly selected using a random method (face-crown).

Clinical examinations were carried out using a visual and tactile method with the aid of a blunt probe and dental mirror by a single trained and calibrated operator (k=0.98). Children aged up to 24 months were examined on a 'MACRI' (a special stretcher used in children)16. Children aged from 25 to 48 months were examined on a dental chair. All of the examinations were carried out with the aid of an artificial light reflector.

If curative treatment was required, the treatment was carried out in the Baby Clinic or in the Basic Unities of Health.

The paired t-test, Mann-Whitney and Chi-Squared test at 5% significance level (BioEstat software, 5.0 version, 2008, Belém/PA, Brazil) were used to analyze the data.

Results

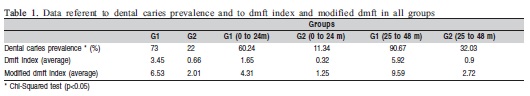

There was a statistical difference for the prevalence of dental caries in the population with and without early dental care (G1 and G2) for the 0-48 months age group (p<0.0001) (Table 1).

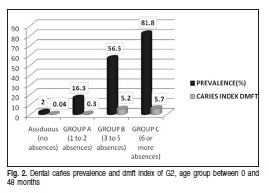

Both groups presented statistically significant differences, and in both cases, the greatest values observed were for G1 [dmft G1 (3.45±3.84) and dmft G2 (0.66±1.57)].It was also found a difference between the dmft index and modified dmft index, within each group, according to a Chi-Squared test (G1 and G2, p<0.0001) (Table 2 and Figure 2).

Assiduity was significant for the G2 group (p<0.0001). Data obtained in the present study confirmed the null hypothesis that assiduity to dental visits positively contributed to the oral health of individuals (Figure 2).

To analyze the influence of assiduity in dental caries prevalence and dmft index and modified dmft, babies who were between 0-48 months in age that were not assiduous to the program was further analyzed (G2 non-assiduous) (Table 3).

Table 3 shows an increasing prevalence of dental caries in relation to assiduity factor. There is a direct relation for the number of absences and the prevalence.

Discussion

In this study G1 and G2 corresponding to ages 0-48 months were subdivided into two groups according to age. The first group was 0-24 months in age while the second was 25-48 months. This division was based on the time of primary teeth appearance since there is a direct relationship between child's age and exposure to cariogenic challenges11,16. In addition, there is a window for the initial acquisition of Streptococcus mutans (between 19 and 31 months) termed the 'window of infectivity'17. However vertical contamination (mother-child) and horizontal contamination (day care center) can occur earlier during the baby's first year of life, suggesting that the period of occurrence of this 'window' may occur earlier for some children18-19. The presence of Streptococcus mutants in children aged six month is related to habits of finger sucking, salivary contact, sharing utensils such as nipples and spoons, and by having their food tasted and/or cooled (blowing it) previously by an adult20. After 13 months of life, children may have already been contaminated depending on habits and level of cariogenic contamination of the family18-19.

In age groups between 0-48 months, 0-24 months and 25-48 months in G1, highest levels of caries prevalence, modified dmft and dmft index described in this study were found (Table 1). In these groups, the results corroborated with the literature5,7,21-22 and clearly showed the need for early oral treatment on health maintenance and disease prevention11,13. These findings are supported by a national survey carried out in 20036 which showed that in children between 18 and 36 months, the average is 1.0 carious teeth per child (without including white spot lesions). According to Kidd and Fejerskok9, it is incorrect not to consider white spot lesions as neglecting this type of lesion causes an underestimation of caries prevalence in some populations. White spots deriving from enamel demineralization are early signs of caries disease, and when not treated, may develop cavited lesions in a period of 6 months to 1 year23.

It is important to emphasize that, in the present study, the positive influence of preventive actions implemented by the program were recorded when compared G2 to G1 (Table 1). These results were similar to obtained by Fracasso et al.24 who concluded that a program of preventive care for babies is more effective than spontaneous demand. The effectiveness of the program developed by the Baby Clinic of the State University of Londrina was already proven11,22, and is supported by our findings.

In the present study, the results showed a statistically significant manifestation of dental caries in G1, compared with G2. The prevalence was proportional to age, as seen between groups G1 0-24 months (60.24%, dmft 1.65) and G1 25-48 months (90.67%, dmft 5.92) and G2 0-24 months (11.34%, dmft 3.2) and G2 25-48 months (32.03%, dmft 0.98). These data also agreed with the literature7,21-22. These results confirm that the most susceptible age for dental caries occurrence is in the first three years of life2,7,21-22. The results suggest that prevention and control measures of dental caries must be reinforced in the program, mainly in the period between the ages of one to three.

Caries lesions of primary teeth are perceived as normal by many mothers, since they do not know this condition. However, dental caries is an infectious and transmissible but preventable disease, which may be controlled by avoiding contamination between mothers and their children18-19.

Parents' previous education, is one of the most important factors for caries prevention in children2,23. Access to these programs at the time of birth will minimize disparities between education levels, and efforts should be directed toward socioeconomic, behavioral and community determinants of oral health5.

Based on the differences between the experience of dental caries in this study, educational programs directed toward parents are needed to establish healthy habits to avoid contamination of the child's oral cavity18-19.

From the data collected, baby oral care is recommended to maintain his/her health, through education in public health programs as an effective way to establish healthy behavior25. The Dentistry for babies is a practical, simple, comprehensive, low-cost and efficient possibility to make parents aware of the cariogenic risks in children at early ages. Therefore parents must be instructed about the necessary dental care. Indeed, it is known that the appropriate time to provide health education is during pregnancy5.

In addition, Tiano et al.26 confirmed that the high prevalence of dental caries in children (d" 36 months of age) is associated with lower socio-economical levels, lower educational levels of mothers, increased time of breast feeding and delay of oral hygiene.

The results of this study suggest that the presence of dental caries in some participants may explain that a few inadequate habits have persisted. It is assumed that this is due to a lack of compliance to the dental program. Although total prevention of the disease was not reached, the reduction of its occurrence and severty constituted an important milestone, which corroborates the findings of Fraiz and Walter11. It is suggested that behavioral factors (difficulties in following orientation suggested by the program, parents' awareness about the disease development) deserve to be reevaluated.

These findings support the conclusion and confirm the hypothesis that assiduity factor positively influenced the dental caries prevalence. In fact, "Babies assiduous to the program", presented lower index of caries than 'Babies not assiduous to the program' (Table 3). In this sense it is essential, in every dental visit, to asses the risk of the child to develop dental caries and highlight to the parents the importance on the correct hygiene of the baby's mouth.

It is believed that it is important to carry out studies to evaluate the reasons why information provided to mothers was not sufficient to make them sensitive to the problem. Low cultural and socioeconomic levels may be factors to be evaluated. To maximize interest, trust, and success among participating parents, educational and treatment programs must be tailored to the social and cultural norms within the community being served. Recruiting mothers during pregnancy improves the likelihood that they will participate in the assessment program26.

The findings of present study reinforce the importance of motivation. Each dental visit should provide new information regarding the developmental phase of the child. It is essential to reinforce the need of follow-up visits in order to parents be aware of the importance of dental visits. Therefore, establishing a relationship with the family, understanding and respecting their cultural aspects, the parents' feelings, respecting the child and re-examining the mother-child relationship is important2.

Based on the results of the present study, it is suggested a follow up regarding the number of times a child aged from 0 to 48 months have dental visits during childhood. In the first year of a baby's life, dental visits should be in the 1st month (if necessary evaluation of anomalies/ breastfeeding), 4th, 8th and 12th month. In the 2nd year of life, an additional four dental visits should occur (15th, 18th, 21st and 24th month). In the 3rd year of life, four dental visits are recommended. Between 36 months and five years of age, two dental visits per year are suggested. The authors agree that in it of the follow up dental visits, the evaluation of a child's risk category, needs assessments and oral examinations must be carried out26, and if necessary, an individualized preventive planning for the child should be done.

In conclusion, the participation in the program had a positive influence on the oral health of babies. Complete assiduity to the program resulted in the lowest rates and prevalence of dental caries.

References

1. Hallett KB, O'Rourke PK. Pattern and severity of early childhood caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2006; 34: 25-35. [ Links ]

2. Fraiz FC. Supervisão de saúde bucal durante a infância. Pesq Bras Odontoped Clin Integr. 2010; 10: 7-8. [ Links ]

3. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on early childhood caries (ECC): Classifications, consequences, and preventive strategies. Pediatric Dent 2011; 33(Sp Issue): 47-9. [ Links ]

4. Kowash MB, Pinfield A, Smith J, Curzon MEJ. Effectiveness on oral health of a long-term health education programme for mothers with young children. Br Dent J. 2000; 188: 201-5. [ Links ]

5. Mouradian WE, Huebner CE, Ramos-Gomez F, Slavkin HC. Beyond access: the role of family and community in children's oral health. J Dent Educ. 2007; 71: 619-31. [ Links ]

6. Brazil. Public Health Department. National coordination of oral health. SB Brazil 2003 Project. Oral health conditions of the Brazilian population 2002-2003. Mainly Results [text on the internet]. Brasília; 2004 [cited 2011 Jul 28]. Available from: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/projeto_sb2004.pdf. [ Links ]

7. Bönecker M, Ardenghi TM, Oliveira LB, Sheiham A, Marcenes W. Trends in dental caries in 1-to 4-years-old children in a Brazilian city between 1997 and 2008. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2010; 20: 125-31. [ Links ]

8. Walter LRF, Nakama RK. Prevention of dental caries in the first year of life. J Dent Res. 1994; 73: 773. [ Links ]

9. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on Periodicity of Examination, Preventive Dental Services, Anticipatory Guidance/Counseling, and Oral Treatment for Infants, Children, and Adolescents. Pediatric Dent. 2009; 33: 102-8. [ Links ]

10. Fraiz FC, Walter LRF. Study of the factors associated with dental caries in children who receive early dental care. Pesqui Odontol Bras. 2001; 15: 201-7. [ Links ]

11. Alves RX, Fernandes GF, Razzolini MTP, Frazão P, Marques RAA, Narvai PC. Evolução do acesso à água fluoretada no Estado de São Paulo, Brasil: dos anos 1950 à primeira década do século XXI. Cad Saúde Pública. 2012; 28(Sp Issue): s69-s80. [ Links ]

12. Ramos-Gomez F, Crystal YO, Ng MW, Tinanoff N, Featherstone JD. Caries risk assessment, prevention, and management in pediatric dental care. Gen Dent. 2010; 58: 505-17. [ Links ]

13. Maltz M, Jardim JJ, Alves LS. Health promotion and dental caries. Braz Oral Res. 2010; 24(sp. Issue): 18-25. [ Links ]

14. Hashim R, Williams S, Thomson WM. Severe early childhood caries and behavioural risk indicators among young children in Ajman, United Arab Emirates. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2011; 12: 205-10. [ Links ]

15. Lemos LVFM, Barbosa DL, Ramos CJ, Myaki SI. Influência do fator assiduidade na prevalência de cárie dentária em indivíduos atendidos na Bebê Clínica da Prefeitura do Município de Jacareí, SP, Brasil. Pesq Bras Odontoped Clin Integr. 2008; 8: 203-7. [ Links ]

16. Caufield PW, Cutter GR, Dasanayake AP. Initial acquisition of mutans streptococci by infants: evidence of a discrete window of infectivity. J Dent Res. 1993; 72: 37-45. [ Links ]

17. Karn TA, O'Sullivan DM, Tinanoff N. Colonization of mutans streptococci in 8-to 15-month-old children. J Public Health Dent. 1998; 58: 248-9. [ Links ]

18. Mohan A, Morse DE, O'Sullivan DM, Tinanoff N. The relationship between bottle usage/content, age, and number of teeth with mutans streptococci colonization in 6-24-month-old children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1998; 26: 12-20. [ Links ]

19. Wan AKL, Seow WK, Purdie DM, Bird PS, Walsh LJ, Tudehope DI. Oral colonization of streptococcus mutans in six-month-old predentate infants. J Dent Res. 2001; 80: 2060-5. [ Links ]

20. Mattos-Granner RO, Pupin-Rontani RM, Gavião MBD, Bocatto HARC. Caries prevalence in 6-36-month-old Brazilian children. Community Dent Health. 1996; 13: 96-8. [ Links ]

21. Morita MC, Walter LRF, Guillain M. Prévalence de la carie dentaire chez des enfants Brésiliens de 0 à 36 mois. J Odonto-Stomatol Pediatr. 1993; 3: 19-28. [ Links ]

22. Weinstein P, Harrison R, Benton T. Motivating mothers to prevent caries: confirming the beneficial effect of counseling. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006; 137: 789-93. [ Links ]

23. Fracasso MLC, Rios D, Provenzano MGA, Goya SJ. Efficacy of an oral health promotion program for infants in the public sector. J Appl Oral Sci. 2005; 13: 372-6. [ Links ]

24. Pinto LMCP, Walter LRF, Percinoto C, Dezan CC, Lopes MB. Dental caries experience in children attending an infant oral health program. Braz J Oral Sci. 2010; 9: 345-50. [ Links ]

25. Tiano AVP, Moimaz SAS, Saliba O, Saliba NA. Dental caries prevalence in children up to 36 months of age attending daycare centers in municipalities with different water fluoride content. J Appl Oral Sci. 2009; 17: 39-44. [ Links ]

26. Feldens CA, Giugliani ER, Vigo Á, Vítolo MR. Early feeding practices and severe early childhood caries in four-year-old children from southern Brazil: a birth cohort study. Caries Res. 2010; 44: 445-52. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Letícia Vargas Freire Martins Lemos

Faculdade de Odontologia de Araraquara

UNESP - Departamento de Clínica Infantil

Rua Humaitá, 1680, CEP: 14801-903

Araraquara, SP, Brasil

E-mail: letvargas@uol.com.br

Received for publication: August 15, 2012

Accepted: December 14, 2012