Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Brazilian Journal of Oral Sciences

versão On-line ISSN 1677-3225

Braz. J. Oral Sci. vol.12 no.1 Piracicaba Jan./Mar. 2013

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Detection of bifid mandibular condyle by panoramic radiography and cone beam computed tomography

Frederico Sampaio Neves; Laura Ricardina Ramírez-Sotelo; Gina Roque-Torres; Gabriella Lopes Resende Barbosa; Francisco Haiter-Neto; Deborah Queiroz de Freitas

Department of Oral Diagnosis, Division of Oral Radiology, Piracicaba Dental School, University of Campinas, Piracicaba, SP, Brazil

ABSTRACT

AIM: To compare panoramic radiography and cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) in the diagnosis of bifid mandibular condyle.

METHODS: The sample consisted of 350 individuals who underwent panoramic radiography and CBCT. In the panoramic radiographs and CBCT images, the presence or absence of bifid mandibular condyle was determined.

RESULTS: Presence of bifid mandibular condyle was detected in four cases (1.1%). In all cases, the relation of one condylar process to the other was mediolateral and history of trauma was reported. None of the individuals had symptoms. In two cases, panoramic radiography did not reveal the presence of bifid mandibular condyle.

CONCLUSIONS: Initial screening for bifid mandibular condyle can be performed by panoramic radiography; however, CBCT images can reveal morphological changes and the exact orientation of the condyle heads.

Keywords: mandibular condyle, computed tomography, temporomandibular joint.

Introduction

The bifid mandibular condyle is a rare disorder, characterized by a division of the head of the mandibular condyle. It was first reported by Hrdlièka (1941)1, who found 27 cases of this anomaly while analyzing male and female dried human skulls. After this, only a few clinical cases have been reported. Bifid mandibular condyle is usually detected in routine panoramic radiographs. The etiology of bifid mandibular condyle remains uncertain, and developmental anomalies, trauma, nutritional disorders, infection, irradiation, genetic factors, teratogenic embryopathy and surgical condylectomy may all be causal factors2.

Bifid mandibular condyle usually affects only one condyle, but bilateral cases have also been reported3-13. Morphology of the bifid mandibular condyle may vary from a shallow groove to two condyle heads and the orientation may be mediolateral or anteroposterior.

Currently, three-dimensional (3D) imaging techniques bring information that leads to more accurate and specific diagnosis of mandibular condyle conditions. Therefore, the aim of this study was to compare panoramic radiography and cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) in the diagnosis of bifid mandibular condyle.

Material and methods

The present retrospective study was carried out following approval of the FOP/UNICAMP Ethics Committee and informed consent was obtained from all volunteers. The sample consisted of 350 individuals who underwent examination by digital panoramic radiography and CBCT. These images were taken as part of routine examination, diagnosis and treatment planning of patients with mandibular condyle conditions.

Digital panoramic radiographs were obtained using an Orthopantomograph OP100 D unit (Instrumentarium Corp., Imaging Division, Tuusula, Finland) operating at 66kVp, 2.5mA and exposure time of 17.6 s. CBCT images were obtained with an i-CAT CBCT unit (Imaging Sciences International, Inc, Hatfield, PA, USA) operating at 120kVp, 8mA, with 0.25mm voxel size and field of view of 13 cm.

The presence or absence of bifid mandibular condyle was determined in the panoramic radiographs and CBCT images. The bifid mandibular condyle was considered from the presence of a shallow groove up to two distinct condyle heads.

Panoramic and CBCT images were evaluated by two oral radiologists with at least 2 years experience with oral diagnosis and who jointly evaluated the images on a computer monitor (21-inch LCD monitor with 1280x 1024 resolution) under dim lighting conditions. The CBCT images were analyzed in all three planes, using XoranCat software version 3.0.34 (Xoran Technologies, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), using the "zoom" tool and manipulation of brightness and contrast. Descriptive analysis of the data was performed.

Results

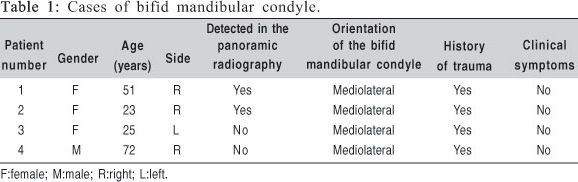

In the present study, bifid mandibular condyle was detected in only four cases (1.1%). The age, gender and affected side are summarized in the Table 1. In all cases of bifid mandibular condyle, the relation of one condylar process to the other was mediolateral and history of trauma was reported. None of the individuals had orofacial pain, inability to open the mouth, infectious history or joint ankylosis (Table 1).

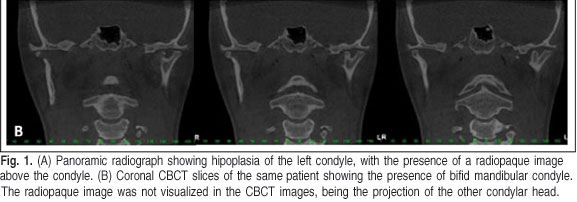

In two cases, the panoramic radiograph did not show the presence of bifid mandibular condyle (Figure 1A), but it was visualized in the CBCT images (Figure 1B). Nevertheless, in these cases, the panoramic radiograph showed altered morphology in the condyle (Figure 1A).

Discussion

Several etiologies have been suggested for the development of bifid mandibular condyle, but there is no agreement about the main causal factor. The genetic origins of such bone abnormalities have been investigated, but minor trauma or developmental factors in utero or during childhood have shown to be the most significant4.

Antoniades et al. (1993)14 suggested that the development of the bifid mandibular condyle is caused by insufficient capacity for remodeling. Quayle and Adams (1986)15 indicated that endocrine disorders, nutritional deficiency, infection, trauma, irradiation and genetic factors may be possible causal factors. Two cases of condylar fracture due to a traumatic bicycle accident that resulted in the formation of a bifid condyle have also been reported16. This relationship confirms the findings of Poswillo (1972)17 who observed the relationship between the formation of bifid condyle and a history of trauma. In the present study, all individuals reported childhood trauma, which is the probable cause for the formation of bifid mandibular condyle.

The prevalence of bifid mandibular condyle is extremely low. Miloglu et al. (2010)13 evaluated 10,200 panoramic radiographs of the Turkish population and found only 32 cases (0.3%) of bifid mandibular condyle, 24 cases (75%) unilateral and 8 cases (25%) bilateral. Menezes et al. (2008)12 examined 50,800 panoramic radiographs of Brazilian subjects and found only 9 cases (0.018%) of bifid mandibular condyle, being 7 unilateral (78%) and 2 bilateral (22%). In both studies, all patients denied history of trauma. In another study, the review of 18,798 panoramic radiographs of Turkish patients revealed 98 cases (0.52%) of bifid mandibular condyle, being 71 unilateral (72.4%) and 27 bilateral (27.6%)18. History of trauma was not investigated. Our results showed a higher prevalence of bifid mandibular condyle (1.1%). Both previous studies above used panoramic radiographs for diagnosis, while we used CBCT images. Therefore, the difference may be attributed to the study method: in the present study the panoramic radiographs failed to detect bifid mandibular condyle in two cases and the diagnosis was based on CBCT images. This shows that the panoramic radiography is not a reliable method to visualize bifid mandibular condyle. To the best of our knowledge, no study has yet compared panoramic radiography and CBCT in the detection of bifid mandibular condyles.

Çaglayan and Tozoglu (2011)19 evaluated the incidental findings in CBCT images of 207 patients and found only 2.9% cases of bifid mandibular condyle. In the present study, the prevalence of bifid mandibular condyle was lower. This difference could be associated with the different populations (Brazilian and Turkish) in the studies.

Symptoms associated with the bifid mandibular condyle are variable. However, the overwhelming majority of cases is asymptomatic5,11-13. If present, the most common symptoms are joint sounds4,20, joint pain21-22, ankylosis23-25 and, more rarely, intermittent joint lock26. In the present study, all individuals with bifid mandibular condyle were asymptomatic.

Morphology of the bifid mandibular condyle can vary from a shallow groove to two distinct condyle heads. The orientation of the two condyle heads can vary between two patterns: mediolateral and anteroposterior. The two patterns of mandibular bifid condyle can be related to its causal factor. According to Szentpétery et al. (1990)27, the bifid mandibular condyle in the anteroposterior direction is the result of childhood trauma, while the condition in the mediolateral direction develops due to the persistence of a fibrous septum in the condylar cartilage. However, Cowan and Fergusson (1997)28 argued that the causal factor does not influence the direction of the bifid condyle, which confirms our case, since the individuals reported history of childhood trauma; however, the bifid mandibular condyle had mediolateral direction in each case.

The appropriate treatment for cases of bifid mandibular condyle depends exclusively on the symptoms of the patient. For symptomatic cases, treatment is the same used in patients with temporomandibular disorders, which opts for the administration of analgesics, anti-inflammatory drugs, muscle relaxants and physical therapy. In cases of joint ankylosis, surgical treatment is the first choice7,21. Due to absence of symptoms experienced by the individuals, no temporomandibular joint treatment was instituted.

CBCT is useful in several areas of dentistry because it shows 3D images of dental structures and offers clear structural images with high contrast. The exposure dose is a major advantage of CBCT when compared with multislice computed tomography and conventional tomography. Examination by CBCT produces an adequate image quality of the maxillofacial region using lower patient exposure doses when compared to multislice computed tomography29-30. In the present study, 3D images were fundamental in the diagnosis of bifid mandibular condyle.

In conclusion, initial screening for the presence of bifid mandibular condyle can be performed by panoramic radiograph, but CBCT images can reveal morphological changes and the exact orientation of the condyle heads.

References

1. Hrdlièka A. Lower jaw: double condyles. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1941; 28: 75-89. [ Links ]

2. Li Z, Djae KA, Li ZB. Post-traumatic bifid condyle: the pathogenesis analysis. Dent Traumatol. 2011; 27: 452-4. [ Links ]

3. Shaber EP. Bilateral bifid mandibular condyles. Cranio. 1987; 5: 191-5. [ Links ]

4. McCormick SU, McCormick SA, Graves RW, Pifer RG, Bilateral bifid mandibular condyles. Report of three cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989; 68: 555-7. [ Links ]

5. Stefanou EP, Fanourakis IG, Vlastos K, Katerelou J. Bilateral bifid mandibular condyles. Report of four cases. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1998; 27: 186-8. [ Links ]

6. Artvinli LB, Kansu O. Trifid mandibular condyle: A case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003; 95: 251-4. [ Links ]

7. Antoniades K, Hadjipetrou L, Antoniades V, Paraskevopoulos K. Bilateral bifid mandibular condyle. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004; 97: 535-8. [ Links ]

8. Alpaslan S, Ozbek M, Hersek N, Kanl A, Avcu N and Frat M. Bilateral bifid mandibular condyle. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2004; 33: 274-7. [ Links ]

9. Shriki J, Lev R, Wong BF, Sundine MJ, Hasso AN. Bifid mandibular condyle: CT and MR imaging appearance in two patients: case report and review of the literature. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005; 26: 1865-8. [ Links ]

10. Espinosa-Femenia M, Sartorres-Nieto M, Berini-Aytes L, Gay-Escoda C. Bilateral bifid mandibular condyle: case report and literature review. Cranio. 2006; 24: 137-40. [ Links ]

11. Acikgoz A. Bilateral bifid mandibular condyle: a case report. J Oral Rehabil. 2006; 33: 784-7. [ Links ]

12. Menezes AV, de Moraes Ramos FM, de Vasconcelos-Filho JO, Kurita LM, de Almeida SM, Haiter-Neto F. The prevalence of bifid mandibular condyle detected in a Brazilian population. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2008; 37: 220-3. [ Links ]

13. Miloglu O, Yalcin E, Buyukkurt M, Yilmaz A, Harorli A. The frequency of bifid mandibular condyle in a Turkish patient population. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2010; 39: 42-6. [ Links ]

14. Antoniades K, Karakasis D, Elephtheriades J. Bifid mandibular condyle resulting from a sagittal fracture of the condylar head. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993; 31: 124-6. [ Links ]

15. Quayle AA, Adams JE. Supplemental mandibular condyle. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1986; 24: 349-56. [ Links ]

16. Thomason JM, Yusuf H. Traumatically induced bifid mandibular condyle: a report of two cases. Br Dent J. 1986; 161: 291-3. [ Links ]

17. Poswillo DE. The late effects of mandibular condylectomy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1972; 33: 500-12. [ Links ]

18. Sahman H, Sekerci AE, Ertas ET, Etoz M, Sisman Y. Prevalence of bifid mandibular condyle in a Turkish population. J Oral Sci. 2011; 53: 433-7. [ Links ]

19. Caglayan F, Tozoglu U. Incidental findings in the maxillofacial region detected by cone beam CT. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2012; 18: 159-63. [ Links ]

20. Loh FC, Yeo JF. Bifid mandibular condyle. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990; 69: 24-7. [ Links ]

21. Corchero-Martín G, Gonzalez-Terán T, García-Reija MF, Sánchez-Santolino S, Saiz-Bustillo R. Bifid condyle: case report. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2005; 10: 277-9. [ Links ]

22. Fernández RF, Flores HF, Mella HS, Lillo TF. Bifid condilar process: case report. Int J Morphol. 2009; 27: 539-41. [ Links ]

23. Sales MA, Oliveira JX, Cavalcanti MG. Computed tomography imaging findings of simultaneous bifid mandibular condyle and temporomandibular joint ankylosis: case report. Braz Dent J. 2007; 18: 74-7. [ Links ]

24. Rehman TA, Gibikote S, Ilango N, Thaj J, Sarawagi R, Gupta A. Bifid mandibular condyle with associated temporomandibular joint ankylosis: a computed tomography study of the patterns and morphological variations. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2009; 38: 239-44. [ Links ]

25. Balaji SM. Bifid mandibular condyle with tempromandibular joint ankylosis - a pooled data analysis. Dent Traumatol. 2010; 26: 332-7. [ Links ]

26. Almasam OC, Hedesiu M, Baciut G, Baciut M, Bran S, Jacobs R. Nontraumatic bilateral bifid condyle and intermittent joint lock: a case report and literature review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011; 69: 297-303. [ Links ]

27. Szentpétery A, Kocsis G, Marcsik A. The problem of the bifid mandibular condyle. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990; 48: 1254-7. [ Links ]

28. Cowan DF, Ferguson MM. Bifid mandibular condyle. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1997; 26: 70-3. [ Links ]

29. Frederiksen NL, Benson BW, Sokolowski TW. Effective dose and risk assessment from film tomography used for dental implant diagnostics. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1994; 23: 123-7. [ Links ]

30. Ludlow JB, Davies-Ludlow LE, Brooks SL, Howeerton WB. Dosimetry of 3 CBCT devices for oral and maxillofacial radiology: CBMercuray, NewTom 3G and i-CAT. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2006; 35: 219-26. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Frederico Sampaio Neves

Departamento de Diagnóstico Oral

Divisão de Radiologia Oral, FOP-UNICAMP

Avenida Limeira, 901

CEP: 13414-903, Piracicaba, SP, Brasil

Phone: +55 19 21065327

E-mail: fredsampaio@yahoo.com.br

Received for publication: November 17, 2012

Accepted: March 04, 2013