Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Brazilian Journal of Oral Sciences

versão On-line ISSN 1677-3225

Braz. J. Oral Sci. vol.13 no.4 Piracicaba Out./Dez. 2014

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Comparison of 2 types of treatment of skeletal Class II malocclusions: a 5-year post-retention analysis

Ana de Lourdes Sá de LiraI; Margareth Maria Gomes SouzaII; Ana Maria BologneseII; Matilde NojimaII

I Universidade Estadual do Piauí – UESPI, Faculty of Dentistry, Department of Orthodontics, Teresina, PI, Brazil

II Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro – UFRJ, Faculty of Dentistry, Department of Orthodontics, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil

ABSTRACT

Aim: To compare 2 types of treatment for Class II malocclusion assessing mandibular behavior in subjects submitted to full orthodontic treatment with standard edgewise appliance and cervical headgear (Kloehn appliance) and those who used cervical headgear in the first period and with full orthodontic appliance in the second period. Methods: The sample consisted of 80 children treated with either cervical headgear combined with full fixed appliances (n=40, group 1), or with cervical headgear at first (n=40, group 2). In both groups, lateral cephalometric radiographs were compared with those made at the beginning of treatment, at its end and at 5-year post-retention phase, in order to quantify the cephalometric measures (8 angular and 3 linear), presenting the mandibular behavior in the antero-posterior and vertical directions. All patients were treated with no extraction and no use of Class II intermaxillary elastics during the full orthodontic treatment. Results: In both groups, the effective treatment of skeletal Class II malocclusion did not interfere in the direction and amount of growth of mandibular condyles and remodeling at the lower border, with no influence on the anti-clockwise rotation of the mandible. The mandibular growth also was observed after the orthodontic treatment, suggesting that it is influenced by genetic factors. Conclusions: These observations may lead to the speculation that growing patients with skeletal Class II malocclusion and low mandibular plane are conducive to a good treatment and long-term stability with one or two periods of treatment.

Keywords: malocclusion; orthodontics; control.

Introduction

The growth potential of individuals with Class II malocclusion is of interest to practicing orthodontists because this type of malocclusion comprises a significant percentage of the cases they treat1. Using Angle's classification as their criterion, several authors have attempted to describe the cephalometric characteristics of the Class II, division 1 malocclusion. The resulting convex profile involves maxillary protrusion, mandibular retrusion or combination of both2.

Class II malocclusion may be accompanied or not by a skeletal discrepancy. The mandible may be normal or retruded relative to the maxilla or the maxilla could be protruded or normal relative to the mandible3-7.

A successful treatment of Class II malocclusion in young people depends on the proper orthodontic mechanics, patient cooperation and how satisfactorily the growth spurt occurs, in ages from 10 to 13 for girls and 11 to 14 years for boys4.

Ricketts8 reported that condylar growth towards antero-superior direction would increase the facial depth and the brachiocephalic pattern. However, a condylar growth towards a posterior-superior direction will result in an increase in the face height with dolicocephalic trends.

Kloehn9 has suggested that Class II malocclusions should be treated with cervical traction during mixed dentition followed by fixed orthodontic appliance without tooth extractions, because of the mandibular alveolar processes and forwards shift of teeth in normal growth.

Most corrections result from a combination of a normal jaw growth pattern accompanied by changes in the maxillary alveolar process and dentition10-11. However, these data are not corroborated by Hubbard et al.12, who reported that there are several variables involved in it, such as angulation of mandibular plane, techniques for using and adjusting the Kloehn appliance, along with the patient's age.

Patients with normal vertical face proportions undergoing orthodontic treatment in the growth spurt phase are more likely to have favorable results and long-term stability10-13.

The objective of the present study was to assess the changes in mandibular behavior of patients submitted to full orthodontic treatment with standard edgewise appliance and cervical traction headgear with those who used cervical headgear first and full orthodontic treatment later.

Material and methods

The UFRJ's ethics Committee approved the development of this study under the protocol number (CAAE 54/2009- 0050.0.339.000/09).

This clinical research was based on one group of 40 individuals (Group 1), 21 girls and 19 boys, who received conventional edgewise fixed appliance and Kloehn cervical headgear treatment during a 25-month period with 12 h/day wearing time of the cervical headgear in just one period of the treatment. In the other group, 40 individuals (Group 2), 23 girls and 17 boys, were treated using a cervical headgear for 12 months (first period) and conventional edgewise fixed appliance and Kloehn cervical headgear for 25 months (second period). The force of cervical headgear applied for the 80 patients averaged 400 g. The onset of treatment was either at the late mixed dentition or at the beginning of the permanent dentition.

All patients were evaluated three times by lateral cephalometric radiographs: at the beginning of the treatment (T0), at the end of the active orthodontic treatment (T1), and at least 5 years out of retention (T2). All subjects were in the pubertal growth spurt period at the beginning of treatment of the skeletal Class II malocclusions, (ANB angle > 5o) and exhibited dental relationship of Class II, division 1 malocclusion according to Angle's classification. All the individuals also exhibited SNGoGn angle <35o. All patients were treated nonextraction and no use of Class II intermaxillary elastics, in the Postgraduate Orthodontic Program of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro.

In Group 1, the mean age for female patients at T0 was 11.4 years (±1.5 years); at T1 was 13.6 years (±1.6 years) and at T2 was 26 years (±1.2 years). For male patients at T0 was 12.2 years (±1.7 years), at T1 was 14.4 years (±1.5 years) and at T2 was 28 years (±1.4 years). In Group 2, the mean age of female patients was 9.8 years (± 1.2 years) in phase T0; 12.9 years (± 1.7 years) in phase T1 and 26 years (± 1.3 years) in phase T2. The mean age of male patients was 10.8 years (± 1.6 years) in phase T0; 14.5 years (± 1.3 years) in phase T1 and 28 years (± 1.7 years) in phase T2.

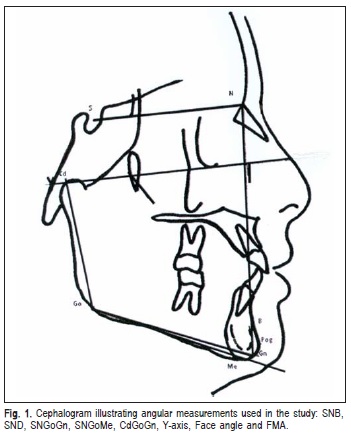

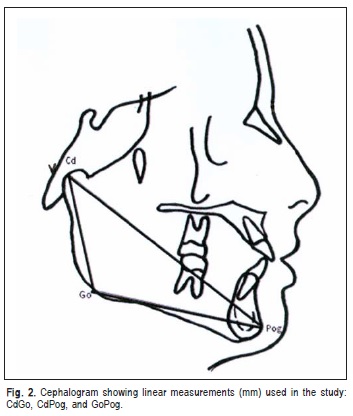

The cephalograms were obtained by delimiting skeletal, dental, and tegumentary structures. The measurements from cephalometric tracings regarding T0, T1 and T2 were tabulated for statistical analysis, with angle measurements rounded up whenever decimal fraction existed. Changes in mandibular displacement were measured in relation to skull base by using the following angles: SNB, SND, SNGoGn, SNGoMe, CdGoGn, Y-axis, Facial angle and FMA (Figure 1). The linear measurements were used to describe separately the mandibular components: CdGo (height of mandibular ramus); CdPog (total mandibular length) and GoPog (mandibular body length) (Figure 2).

Means and standard deviations were calculated for each cephalometric measurement at T0, T1 and T2. The statistical treatment of the data between T0 x T1 as well as between T1 x T2 was performed using the paired Student's t test with 5% significance level. Unpaired t tests were used to evaluate the differences in therapeutic effects and the length of active treatments between the groups. Pearson's r correlation coefficient was applied to determine whether any skeletal or dental characteristics and age were related to the length of active treatment.

Error of the method

To evaluate the error of the method, 30 radiographs chosen at random were traced and digitized by the same investigator on 2 separate occasions at least 2 months apart. The Dahlberg14 formula was used: ME =\/Σ d2/2n, where n is the number of duplicate measurements. Random errors varied between 0.26 and 0.92mm for linear measurements and between 0.280 and 0.370 for angular measurements.

Results

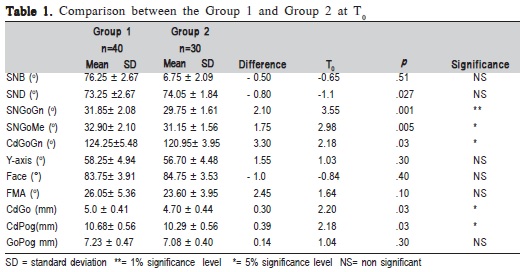

Both groups had comparable mean cephalometric values for angular measurements: SNB, SND, Y-axis, Facial angle l and FMA, and for linear measurements, GoPog. However, the mandibular plane angles: SNGoGn and SNGoMe were 2.10 and 1.80 greater in Group 1 than in the Group 2, respectively (Table 1). The angular measurement CdGoGn was 3.30° bigger in the Group 1 than in Group 2. The linear measurements CdGo and CdPog were slightly larger in Group1 (0.3 cm and 0.39 cm respectively) than in Group 2 (Table 2).

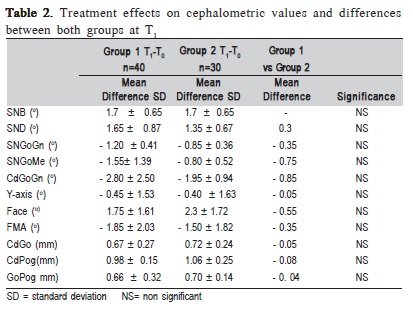

During the treatment, the SNB angle increased an average 1.70 (± 0.650) in both groups. In Group I the SND angle increased an average 1.650 (± 0.870) and 1.350 (± 0.670) in Group 2. The angles SNGoGn, SNGoMe and CdGoGn decreased respectively 1.200, 1.550 and 2.80° in Group 1 and 0.850, 0.800 and 1.950 in the Group 2. In both groups the Yaxis angle decreased 0.40 whereas the Facial angle increased 1.750 (± 1.610) in Group 1 and 2.30 in Group 2. In both groups the linear measurements CdGo, CdPog and GoPog increased with approximate values. The mean differences between the 2 groups for all analyzed measurements were not statistically significant.

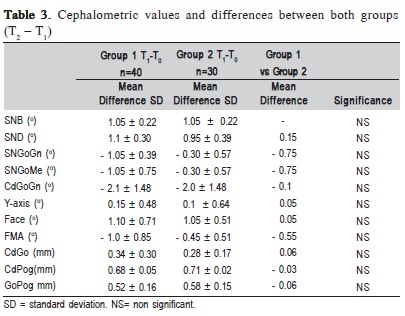

At the post-retention phase the SNB angle increased an average 1.050 (± 0.220) in both groups, whereas the SND angle increased 1.10 in Group 1 and 0.950 in Group 2. The angles SnGoGn, SnGoMe and CdGoGn also decreased in average respectively 1.050, 1.050 and 2.10 in Group1 and 0.30, 0.30 and 20 in Group 2. The Y-axis increased slightly 0.150 (± 0.480) in Group 1 and 0.10 (± 0.640) in Group 2. The Facial angle increased 1.10 (± 0.710) in Group 1 and 1.050 (± 0.510) in Group 2, whereas the FMA angle decreased slightly, in average 10 in Group1 and 0.450 in Group 2. In both groups the linear measurements also increased, but with approximate values. The mean differences between the 2 groups for all analyzed measurements were not statistically significant.

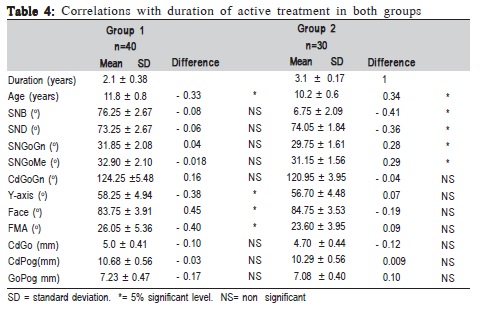

Treatment was moderately inversely related to age at T0 in both groups (r=-0.33 for Group1 and r=0.34 for Group 2); the younger patients had longer treatments. In the same way the Y-axial, Face and FMA angles were inversely related to age at T0 in Group 1. In Group 2, the angular measurements SNB, SND, SNGoGn, SNGoMe were also inversely related to age at T0. There was no correlation with the other initial tested variables in both groups.

Discussion

The skeletal changes resulting from face growth, which occurs during the transition from deciduous to permanent dentition, do not correct the Class II malocclusion established at an earlier age. It probably happens due to the morphological characteristics of the Class II malocclusion, justifying the therapeutic intervention during the growth spurt15-16 as was observed in this study.

For dental Class II and moderate skeletal discrepancy in growing children, two methods of treatment were compared to assess their cephalometric effects at the end of comprehensive treatment and at post retention.

While assessing the mandibular behavior of the study group, it was observed that the mechanics of a conventional edgewise fixed appliance and Kloehn cervical headgear used for orthodontic treatment did not interfere with the mandibular growth and displacement, since the mean values for SNB angle had a statistically significant increase in the T0 - T1 interval. This was observed in Group 1 that received conventional edgewise fixed appliance and Kloehn cervical headgear treatment for 25 months, as well as in Group 2 that was treated using a cervical headgear for 12 months (first period) and conventional edgewise fixed appliance and Kloehn cervical headgear for 25 months (second period). This demonstrated a favorable mandibular growth in relation to the skull base during the phase of active orthodontic treatment, which was confirmed by an expressive increase in the SND angle. Therefore there are no outcome differences between the two types of treatment because the selected sample showed horizontal facial growth, with favorable mandibular and maxillary growth, in down and forward directions. Similar conditions were observed in the T1 - T2 interval regarding the mean SNB and SND angles, which could be the result of residual mandibular growth after the active orthodontic treatment period (Tables 2 and 3)15.

Interestingly, the 12 months difference in treatment length corresponded approximately to the time that only the Kloehn cervical headgear was worn. An explanation of this variation in treatment duration is the age at T0; Kloehn cervical headgear was used relatively early in patients of Group 2, who were far from full permanent dentition or far from their maximum growth potential during puberty. This was confirmed in younger patients, who showed slower increase in the SNB,SND, SNGoGn and SNGoMe measurements and total treatment time longer than Group 1 (Table 4).

With regard to the profile, a mean reduction of the face convexity was found in the time intervals, which was confirmed by a significant increase of the face angle. This fact may be supported by the anterior positioning of the mandible during facial growth (Tables 2 and 3) as well as bone apposition in the pogonion region in both groups5,17.

The cephalometric evaluation showed a decreasing trend of the angles related to the mandibular plane during growth due to the intrinsic morphogenetic characteristic of the studied cases18-19. All patients submitted to orthodontic treatment presented low mandibular plane, which is a crucial factor for using cervical traction as mentioned in other studies2,5,17. The mean values for SNGoGn, SNGoMe, CdGoGn and FMA angles showed a significant reduction in the time interval, suggesting that rotation of the mandible is ruled by the direction and amount of condylar growth and remodeling at the lower border of the mandible in both groups (Table 2)15,19-20.

According to the structural analysis established by Björk3, the mandibular rotation depends on the morphogenetic pattern, which is determined by the mandible morphology. The vertical growth of mandibular condyles should be greater than that of posterior alveolar processes and is an important factor in the anti-clockwise rotation of the mandible21. Nevertheless, the changes observed in the Y-axis angle revealed the harmonic pattern of face growth in both groups during orthodontic treatment and post-retention phases (Tables 2 and 3)11,22-23.

Analysis of the linear measurements CdGo, CdPog and GoPog (Tables 2 and 3) showed a significant increase in T0 - T1 and T1 - T2 intervals. These data also suggest that mandibular growth occurs during the active orthodontic treatment as well as post-retention period, including an increase in both mandibular ramus and body due to the condylar growth and bone apposition in the pogonion region. According to the literature, the mandibular growth is more prominent than the maxillary growth, continuing for an additional period of time11,22,24.

Amount and direction of mandibular growth are genetically determined. The lower border of the mandible influences the mandibular plane angle because of bone remodelling (Tables 2 and 3)10. The mean values for SNGoGn, SNGoMe, CdGoGn, and FMA angles were reduced in both groups of patients between T0 - T1, demonstrating favorable condylar growth and remodeling at the lower border of the mandible. In this way, anti-clockwise rotation of the mandible was observed in the patients, which was confirmed by the significant reduction in CdGoGn and FMA angles2,4. Between T1 - T2, all the angular measurements cited above were found to be significantly decreased for all patients, suggesting that both growth and displacement of the mandible are determined by genetic factors (Tables 2 and 3)3,10.

Analysing the mean values regarding the linear measurements CdGo, CdPog, and GoPog (Tables 2 and 3), a significant increase in both time intervals for both groups was found. This emphasized the mandibular growth observed during and after the active orthodontic treatment phase. Similar results were also found by other authors, who reported a residual mandibular growth11,22,24. The apposition in the region of pogonion occurs continuously even after the active treatment is finished17-19.

Full corrective orthodontic treatment, using concurrently standard edgewise technique and cervical headgear (Kloehn appliance), was considered effective in patients with skeletal Class II malocclusions and low mandibular plane as well as just cervical headgear was used at first period, followed by full corrective orthodontic treatment and cervical headgear. The treatments did not interfere in mandibular growth, which happened during the active treatment as well as after it finished. These observations may lead to the speculation that growing patients with skeletal Class II malocclusion and low mandibular plane are conducive to a good treatment and long-term stability with one or two periods of treatment.

References

1. Angle E. Classification of malocclusion. Dent Cosmos. 1899; 41: 248-64. [ Links ]

2. Jacob HB, Buschang PH. Mandibular growth comparisons of Class I and Class II division skeletofacial patterns. Angle Orthod. 2014; 84: 755-61.

3. Janson G, Goizueta OEFM, Garib DG, Janson M. Relationship between maxillary and mandibular base lengths and dental crowing in patients with complete class II malocclusions. Angle Orthod. 2011; 81: 217-21.

4. Boccetti T, Stahl F, McNamara JA Jr. Dentofacial growth changes in subjects with untreated Class II malocclusion from late puberty through young adulthood. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009; 135: 148-54.

5. 5.Hassan AH. Cephalometric characteristics of Class II division 1 malocclusion in a Saudi population living in the western region. Saudi Dent J. 2011; 23: 23-7. 6.

6.Al-Khatecb EA, Al-Khatecb SN. Anteroposterior and vertical components of Class II division 1 and division 2 malocclusion. Angle Orthod. 2009; 79: 859-66.

7. Saltazi H, FloresMir C, Mazor PW, Yowsef M. The relationship between vertical facial morphology and overjet in untreated Class II subjects. Angle Orthod. 2012; 82: 432-40.

8. Ricketts RM. Planning treatment on the basis of the facial pattern and an estimate of its growth. Angle Orthod. 1957; 27: 14-37.

9. Kloehn S. Evaluation of cervical anchorage force in treatment. Angle Orthod. 1961; 31: 91-104.

10. Bjork A. Variations in the growth pattern of the human mandible: longitudinal radiographic study by the implant method. J Dent Res. 1963; 42: 400-11.

11. Fidler BC, Artun J, Joondeph DR, Little RM. Long-term stability of Angle Class II, division 1 malocclusions with successful occlusal results at end of active treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1995; 107: 276-85.

12. Hubbard GW NRS, Currier G F. A cephalometric evaluation of non extraction cervical headgear treatment in class II malocclusion. Angle Orthod. 1994; 64: 359-70.

13. Franchi L, Pavoni C, Faltin K Jr, McNamara JA Jr, Cozza P. Long term skeletal and dental effects and treatment timing for functional appliances in Class II malocclusion. Angle Orthod. 2013; 83: 334-40.

14. Dahlberg G. Statistical methods for medical and biological students. London: Allen & Unwin; 1940.

15. Flores-Mir C, McGrath L, Heo G, Major P. Efficiency of molar distalization associated with molar eruption stage. A systematic review. Angle Orthod. 2013; 83: 735-40.

16. Baccetti T, Franchi L, Kim LH. Effect of timing on the outcomes of 1-phase nonextraction therapy of class II malocclusion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009; 136: 501-9.

17. Garbui IU, Nouer PR, Nouer DF. Cephalometric assessment of vertical control in treatment of Class II malocclusion with a combined maxillary splint. Braz Oral Res. 2010; 24: 34-9.

18. Lira ALS, Souza MMG, Bolognese AM. Long-term maxillary behavior in treated skeletal Class II malocclusion. Braz J Oral Sci. 2012; 11: 120-4.

19. Carter NE. Dentofacial changes in untreated Class II division 1 subjects. Br J Orthod. 1987; 14: 225-34.

20. Kim J, Nielsen LA. A longitudinal study of condilar growth and mandibular rotation in untreated subjects with Class II malocclusions. Angle Orthod. 2002; 72: 105-11.

21. Klocke A, Nanda RS, Kahl-Nieke B. Skeletal Class II paterns in the primary dentition. Am J Orthod. 2002; 121: 596-601.

22. Lira ALS, Izquierdo A, Prado S, Nojima LI, Nojima M. Mandibular behavior in the treatment of skeletal Class II malocclusion: 5 years post-retention analysis. Braz J Oral Sci. 2009; 8: 166-70.

23. Kirjavainen M, Hurmerinta K, Kirjavainen T. Facial profile changes in early Class II correction with cervical headgear. Angle Orthod. 2007; 77: 960-7.

24. Lira ALS, Izquierdo A, Prado S, Nojima M, Maia L. Anteroposterior dentoalveolar effects with cervical headgear and pendulum.

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Ana de Lourdes Sá de Lira

Departamento de Ortodontia,

Faculdade de Odontologia

Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro

Av. Professor Rodolpho Paulo Rocco, 325

Ilha do Fundão - CEP: 21941-617

Rio de Janeiro - RJ - Brasil

E-mail: anadelourdessl@hotmail.com

Received for publication: July 21, 2014

Accepted: November 25, 2014