Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Brazilian Journal of Oral Sciences

versão On-line ISSN 1677-3225

Braz. J. Oral Sci. vol.14 no.4 Piracicaba Out./Dez. 2015

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Dentists' actions about oral health of individuals with Down Syndrome

Ana de Lourdes Sá de LiraI; Claudio Inácio Reis da SilvaI; Sylvana Thereza de Castro Pires RebeloI

I Universidade Estadual do Piauí – UESPI, School of Dentistry, Department of Clinical Dentistry, Area of Integrated Clinic, Parnaíba, PI, Brazil

ABSTRACT

Aim: To investigate the knowledge and actions of dentists for treatment of individuals with Down syndrome. Methods: A questionnaire was applied to all the dentists (n=90) working at the FHS (Family Health Strategy) modules in the urban limits of Parnaíba, PI, Brazil. Four of the questions in the questionnaire were written according to the Theory of Planned Behavior Table and Likert scale (questions 6,7,9 and 15), in order to analyze the professionals' intentions. Sixteen objective questions were elaborated with the purpose of collecting information about the degree of the dentists' knowledge as regards the intention of attending courses in the patients with special needs area including DS, and interaction with other professionals and families. The option was to use a questionnaire applied to the dentists of the region, from August to November 2014. Results: It was found that most professionals were women and they considered themselves able to identify these patients. Among the professionals, 70% showed they had no difficulty in identifying the patient with DS, and 5.2% had no opinion about the subject. Only 6.6% of the professionals showed to be certain about their aptitude to attend to these patients; 70% were partially apt, that is, they were not absolutely sure about their aptness. There was a statistical relationship between the variables understanding and difficulty in the treatment. There was no statistical relationship between the variable capacity to identify, understanding of the needs and fitness variable in attendance. Conclusions: Patients with Down syndrome need more attention and care of dentists, they must also be involved in a multidisciplinary approach. Most of the professionals do not follow the procedures laid down by the Ministry of Health, but showed interest in attending a course in this area and there is a low number of SD patients being cared in Parnaíba, PI.

Keywords: Down Syndrome; oral health; quality of life.

Introduction

Down syndrome, a chromosomal anomaly in chromosome 21 was described in the 19th Century and was the first chromosomal anomaly detected in the human species. Those affected by the syndrome may present various alterations1.

Oral health is an important aspect for social inclusion of persons with disabilities. Oral diseases and oral malformations rarely result in risk of death, but they cause conditions of pain, infections, respiratory complications and masticatory problems. From the esthetic point of few, characteristics such as bad breath, poorly positioned teeth, traumatisms, gingival bleeding, the habit of keeping the mouth open and drooling may mobilize feelings of compassion, repulsion and/or prejudice, accentuating attitudes of social rejection2-5.

There is a set of alterations associated with Down syndrome (DS), which demand special attention, requiring special exams for their identification, as well as general and oral implications, which must be known by the dentist. This is to enable the dentist both to identify them and handle the patient with regard to aspects of psychological, anatomical and medical interactions6-10.

It is imperative that the dentists be aware about the diagnosis of signs and symptoms inherent to these patients and the possible complications that may arise at the time of intervention. The treatment demands the work of a multiprofessional team that must stay in communication in order to provide better treatment, associated with the participation of family members, in order to improve quality of life for these individuals11-16.

Dental attention provided as early as possible is of the utmost importance to this population, in order to prevent future wider problems and to help patients create habits that will perpetuate through their lifetime17-22.

The present philosophy of dental treatment in basic care, directed towards early preventive and restorative actions, did not consider this part of special individuals, who find themselves faced with predominantly surgical and mutilating treatments. The development of health promotion activities, with a multidisciplinary health team, directed towards patients with DS and their caregivers has become indispensable in view of the precarious oral condition of such patients10-22.

The aim of this research was to investigate the knowledge and actions of dentists in the treatment of individuals with Down syndrome.

Material and methods

The epidemiological study design was of the observational, transversal, non-probabilistic type, with a sample composed by dentists of the public Base Care network in the city of Parnaíba, PI, Brazil. The option was to use a questionnaire applied to the dentists of the region, from August to November 2014. The pilot project, performed in June, 2014, was carried out by a single researcher, with the aim of verifying the suitability of the questionnaires to be used in the research. The participants were 25 students of the 10th semester at the State University of Piaui, Brazil.

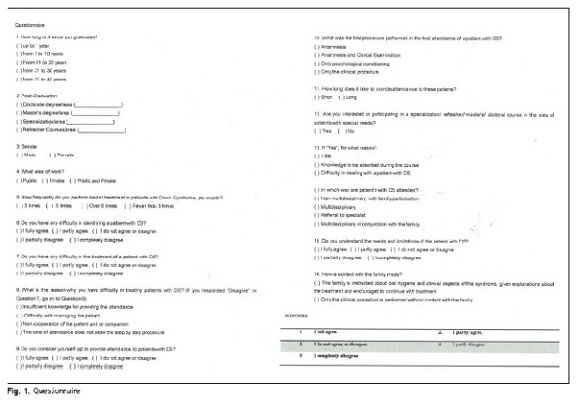

The questionnaire was applied to all the dentists (n=90) working at the FHS (Family Health Strategy) modules in the city of Parnaíba, in the northeastern region of Brazil (Figure 1). The following exclusion criteria were considered in this study: refusal by the professional to answer the questionnaire, incomplete filling out of the applied questionnaires.

The participants signed an Informed Consent Form, after being informed that their participation was optional, confidential, the information would not be used to harm them, there was no possibility of any risks and they could step out from the research at any time. The present study was submitted to the Ethics Committee on Research with Human Beings, of the State University of Piauí – UESPI, protocol CAAE (36950714.6.0000.5209), and Report No. 1.125.322, which complied with its requisites and requests, and was in accordance with the National Health Council Resolution No.196/96, which rules the ethics in research with human beings in Brazil.

Data were collected by application of the research form. The professional answered the questionnaire after selecting one or more options for each question, which was checked by the researcher. On conclusion of the interview, the interviewed professional signed the form of questions, evaluating the veracity of his/her responses.

Four of the questions in the questionnaire were elaborated according to the Theory of Planned Behavior Table, and Likert scale (questions 6, 7, 9 and 15), in order to analyze the professional's intents.

To analyze the questions with reference to identification, aptitude, understanding of the limitations and difficulties in treatment, the Likert Scale was used in the area of social sciences, which is considered easy to understand9. The questionnaire was divided according subjective norms, behavioral beliefs and internal control beliefs, with questions ordered by categories and relevant to the topic, which considers the aspects of belief, values and attitude. The fivepoint scale ranged from "I fully agree", (meaning being certain as to the answer), "I partially agree", (meaning not sure), "Completely disagree", (showing negative certainty), "I partially disagree" (partial negative certainty, doubt) and to "I do not agree or disagree" (the interviewed professional has no opinion on the subject).

Sixteen objective questions were elaborated for collecting information about the degree of the dentist's knowledge as regards the intention of attending courses in patients with special needs area, including DS and interaction with other professionals and families.

The research included aspects such as gender, time since graduation, frequency of attendance to patients with DS, the used form of treatment, taking into consideration the ease of identifying the patient, personal aptitude in attendance, understanding of the needs and whether they had any difficulty with the treatment.

The responses were tabulated in the Excel program according to the individual questions and answers, for statistical analysis in the "Biostats 5.3" program. Multiple linear regression tests were used to analyze the determinant and independent variables, and simple logistic test to evaluate the dichotomic variables.

An inter-rater agreement statistic (Kappa) was calculated to evaluate the agreement for nominal scales between two observers that performed the research and verify if the methodology can be applied in other population or in other city. The value of K was 0.89, a very strong agreement.

Results

There was no significant difference as regards gender, remembering that among the interviewed professionals, 26 were women. The professionals had a mean 6 years since graduation and aged between 21-30 years; 39 had specialization and refresher courses; 35 only refresher courses; 15 only specialization, and only 1 academic master's degree, but there was no post-graduation in Patients with Special Needs.

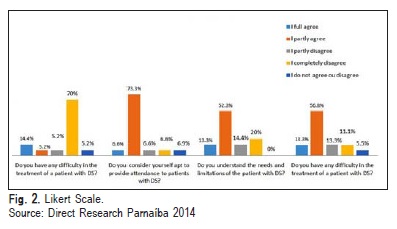

All professionals informed they performed fewer than 3 attendances per month to patients with DS. Out of the professionals, 70% showed they had no difficulty in identifying the patient with DS, and 5.2% had no opinion about the subject. Only 6.6% of the professionals have shown to be certain about their aptness to attend these patients; 70% were partially apt, that is, they were not absolutely certain about their aptitude. The other parts showed no significant values with regards to the question. Out of the professionals 13.3% were found to have complete understanding of the needs and limitations of patients with DS; 52.3% of the participants understood partly these needs and limitations and 20% did not understand. 56.8% affirmed they had difficulties with the treatment of patients with DS; 26.6% had a certain amount of difficulty and 5.5% had no opinion (Figure 2).

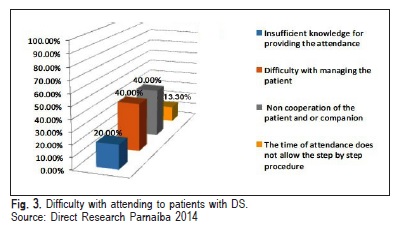

Among the participants, 66.7% answered they had difficulties with treatment; 20% attributed this difficulty to insufficient knowledge for providing attendance; 40% to difficulty in handling the patient; 40% because the patient was non-cooperative and 13.3% because the time of attendance did not allow the process to be performed step by step. For this question only the participant could choose more than one alternative (Figure 3).

About the procedure on the first consultation and time of attendance, 20% reported performing anamnesis as the initial procedure, 60% anamnesis and clinical exam; 13% psychological conditioning, and 7% the clinical procedure only, with the majority (80%) spending a long time to provide the attendance. As regards handling/management of the patient, 60% answered that they did so in a multidisciplinary manner, but in conjunction with the family. The remaining 40%, referred the patient to a specialist.

Out of the professionals, 60% showed interest in qualifying themselves in the area and 40% did not consider this option. Of these 60% who showed interest, the reason was the knowledge to be acquired during the course for 60%, and for the remaining 40%, it was the difficulty of dealing with patients with DS.

As regards the difficulty of treating the patients with DS and understanding their needs and limitations, a significant correlation was verified by the multiple linear regression test (p=0.005). Thus, 50% of the dentists were found to agree partially about having difficulty with treatment, and not having a good basis on the patient's needs and limitations.

Statistical analysis was performed among the variables "Difficulty with identifying the patients with DS", "Aptness for attendance", "Understanding of the needs of the patient with DS" and "Degree of difficulty with treatment of the patient with DS" by the multiple logistic regression test, where no statistical relationship was found (p>0.05).

Most professionals had difficulty with handling the patient (40%) due to lack of cooperation from the patient (60%), a relationship proved by multiple logistic regression test (p=0.0346).

Simple logistic analysis between the difficulty with identifying the patient with DS and the difficulty with treatment showed there was no correlation (p=0.4269), revealing that in spite of the professionals having no difficulty with identifying the patient with DS, they appeared to have a certain impasse with regards to treatment.

There was correlation between the interest in attending courses in the area of patients with special needs and knowledge to be acquired during the course (p=0.0023).

Discussion

Most of the professionals who participated in the research were women, aged between 21-30 years, none was older than 40 years, and had a mean of 6 years since graduation. This distribution, which is in agreement with the national mean value, was 26-35 years6.

The fact that most of the professionals were postgraduates, does not mean to say they were able to care for the patient with DS, considering they were not specialists in the area of patients with special needs, which includes these patients. According the the Federal Council of Dentistry (CFO) there were 480 registered specialists in patients with special needs throughout Brazil as of 16/08/2015, out of a total number of 237.872 dentists. According to data of the Federal Council of Dentistry, the Piauí State has 2.488 dentists, with only one registered as professional in the abovementioned specialty.

The low number of patients attended to per month is cause for concern, as the importance of dental attendance for the patient with DS starting at early childhood is known, so that preventive, interceptive and curative activities may be provided11-12.

The lack of entry to dental assistance by patients with special needs, a group comprising DS, may be attributed to different factors: the professionals' lack of knowledge and preparedness for attendance, changed information about the oral health conditions and dental needs, negligence of dental treatment provided by public and private services and the parents' disbelief in the importance of oral health13.

In spite of the high number of professionals able to identify the patient with DS (73.3%), there are few who fully understand the needs of the patient with DS (13.7%), in addition to showing difficulty with treatment (63.7%). These data show the dentists' lack of preparation, or lack of attention to the oral health of these patients with DS, a common fact observed by other authors16-17,20,22 when they affirmed that lack of dental care is a health problem frequently found in children with DS.

The fact that dentists had no difficulty in identifying these patients, but had difficulty in handling them, is probably due to the fact that the professional has not been prepared during his/her academic life for providing attendance to patients with special needs, as has also been suggested by some authors15-16. This also suggests that while attending the patient with DS and after obtaining the guardian's consent and signature, meticulous questioning must be carried out, and whenever possible, observations about the patient's systemic condition, such as: verifying the use of medications that may interfere in dental treatment; referring the patient to the physician when doubt arises about systemic changes observed in the interview; during the interview, observe possible evidence of maltreatment, lack of care or neglect.

At the end of the research, a folder was delivered with guidance about oral health promotion, in accordance with the advice of authors9,11,14,20-21, in which preference should be given to preventive methods for oral health of patients DS, beginning right in the first year of life and annually, performing clinical and radiographic exams. And also to instruct the family about the importance of good oral hygiene and daily use of dental floss, of observing the daily amount of fluorides and dentifrices used, due to the risk of swallowing them and explaining to parents about delay in the eruption of teeth.

However, this research found that only 20% of dentists perform only anamnesis; 60% perform anamnesis and clinical exam; 13% psychological conditioning and 7% perform only the clinical procedures, which is not recommended by some authors17-19 who are unanimous stating that such procedures may generate discomfort to patients and an unfavorable experience, thereby compromising healthy treatment.

For some authors9,12,14,17-21 the dental attention to these patients is extremely important and is influenced by the attitude of the dentist in care of them, so that it is crucial a behavior that transmits confidence to patients. Moreover, the time of consultation for each patient should be short and strictly calculated, so it does not exceed 30 minutes, differing from the results found in the research, in which 80% of the professionals reported spending a long time on the attendance of these patients.

The oral health of patients with DS may be compromised due to professional´s lack of specific knowledge about treating special patients, in addition to the negligence of their parents2-5.

With regard to the mode of attendance to these patients, analysis of the data showed that 60% of the professionals did not use a multidisciplinary approach, but one in contact with the family, explaining about the oral aspects of the syndrome, and 40% of the professionals reported referring the patient to a specialist. However, as previously described, Piaui has only one professional in the specialty registered with the CFO, responsible for this population. Therefore, these patients probably were not attended by a specialized professional6,10-12,14,20,22.

None of the professionals worked in a multidisciplinary manner; they did not interact with other professionals and did not perform multidisciplinary management along with the family as observed by other authors7-8,11-13. However, this negative fact does not mean non-fulfillment of professional duties. A multiprofessional approach is described as the one in which there is reference and counter-reference, however, if the patient does not achieve one of the points the cycle is broken. This fact may frequently be explained by the distance, or difficulty with the patient's residence from the center of reference.

Various studies have pointed out the importance of the manner of approaching these patients, thus the multidisciplinary manner prevails. Since the term Syndrome signifies "a set of signs and symptoms", it should be approached at multidisciplinary level, which along with the family, offers better conditions for the patient's quality of life 20-22.

The importance of the professional's interaction was pointed out, with the purpose of elucidating thise issue, emphasizing the involvement of family members in the treatment of patients with DS. Differently from what was observed in the research, some authors11-13,19-21 have found the absence of family involvement in this process, probably due to the limitations of multidisciplinary integration in the area of health.

The shared care of the patient with DS should be in conjunction with the diagnosis, constructing the therapeutic project, therapeutic goals, re-evaluating and following up progress. In addition, the discourse was about the importance of co-responsibility for the process of care among the professionals, the subject and the family, according to some authors6-7,11,22.

On conclusion, the majority of dentists showed interest in qualifying themselves in this area, with a view to increase knowledge, with the possibility of reflecting in the improvement in attendance of patients with DS, who need dental care in a multidisciplinary context. Most of them in Parnaíba, PI, do not follow the clinical conduct recommended by the Ministry of Health for the attendance of these patients. A low number of attendances to the patients with DS were recorded, but with positive family involvement. Nevertheless, professionals from other areas required for overall attendance of the patient were not inserted, which is unfavorable to the concept of a multidisciplinary approach.

Our hope is that the results of this study may encourage providing a larger number of training and qualification courses to dentists and members of the HMF, who intend providing with patients Down syndrome a higher quality of care, and for the elaboration of preventive and educational programs.

The interpretation of the present results should consider some limitations inherent to this study. It is very important that future studies assess if individuals with Down syndrome keep being assisted by the FHS. The city where the study was conducted is also considered an undeveloped city in Brazil, both economically and socially, which may explain the small number of patients that use FHS.

References

1. Hennequim M, Faulks D, Roux D. Accuracy of estimation of dental treatment need in special care patients. J Dent. 2000; 28: 131-6. [ Links ]

2. Lee SR, Kwon HK, Song KB, Choi YH. Dental caries and salivary immunoglobulin A in Down syndrome children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2004; 40: 530-3.

3. Fung K, Allison P. A comparison of caries rates in non-institutionalized individuals with and without Down syndrome. Spec Care Dentist 2005; 25: 302-10.

4. Frydman A, Nowzari H. Down syndrome-associated periodontitis: a critical review of the literature. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2012; 33: 356-61.

5. Kaye PL, Fiske J, Bower EJ, Newton JT, Fenlon M. Views and experiences of parents and siblings of adults with Down syndrome regarding oral health care: a qualitative and quantitative study. Br Dent J. 2005; 198: 571-8.

6. Atunes JLF, Narvai PC, Nugent ZJ. Measuring inequalities in the distribution of dental caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2004; 32: 41-8.

7. Minnes P, Steiner K. Parent views on enhancing the quality of health care for their children with fragile X syndrome, autism or Down syndrome. Child Care Health Dev. 2009; 35: 250-6.

8. Wong DF, Lam AY, Chan SK, Chan SF: Quality of life of caregivers with relatives suffering from mental illness in Hong Kong: roles of caregiver characteristics, caregiving burdens, and satisfaction with psychiatric services. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012; 10:15. doi: 10.1186/1477- 7525-10-15.

9. Shore S, Lightfood T, Ansell P. Oral disease in children with DS: causes and prevention. Community Pract. 2010; 83(2): 18-21.

10. Areias CM, Sampaio-Maia B, Guimarães H, Melo P, Andrade D. Caries in Portuguese Down syndrome children. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2011; 66: 1183-6.

11. Khocht A, Janal M, Turner B. Periodontal health in Down syndrome: contributions of mental disability, personal, and professional dental care. Spec Care Dent. 2010; 30: 118-23.

12. Wilson MD. Special considerations for the dental professional for patients with Down's syndrome. J Okla Dent Assoc. 1984; 84: 24-6.

13. Anders P, Davis EL: Oral health of patients with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review. Spec Care Dent. 2010; 30: 101-17.

14. Khocht A. Subgingival microbiota in adult Down syndrome periodontitis. J Periodont Res. 2012; 47: 500-7.

15. Sousa E, Alberman E, Morris JK. Down Syndrome and Paternal Age, a new analysis of case–control data collected in the 1960s. Am J Med Genet A. 2009; 149: 1205-8.

16. Mathias MF, Simionato MR, Guare RO. Some factors associated with dental caries in the primary dentition of children with Down syndrome. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2011; 12: 37-42.

17. Vijayaprasad KE, Ravichandra KS, Vasa A, Suzan S. Relation of salivary calcium, phosphorus and alkaline phosphatase with the incidence of dental caries in children. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2010; 28: 156-61.

18. Oliveira AC, Pordeus IA, Torres CS, Martins MT, Paiva SM. Feeding and nonnutritive sucking habits and prevalence of open bite and crossbite in children/adolescents with Down syndrome. Angle Orthod. 2010; 80: 749-53.

19. Vilella PGDP, Costa PP. Periodontite na Síndrome de Down. Rev Odontol Planalto Cent. 2013; 3: 71-6.

20. Davidovich E, Aframian DJ, Shapira J, Peretz B. A comparison of the sialochemistry, oral pH, and oral health status of Down syndrome children to healthy children. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2010; 20: 235-41.

21. Bonanato K, Pordeus IA, Compart T, Oliveira AC, Allison PJ, Paiva SM. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of a Brazilian version of an instrument to assess impairments related to oral functioning of people with Down syndrome. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2013; 11: 4. doi: 10.1186/ 1477-7525-11-4.

22. Oliveira AC, Pordeus IA, Luz CL, Paiva SM. Mothers' perceptions concerning oral health of children and adolescents with Down syndrome: a qualitative approach. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2010; 11: 27-30.

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Ana de Lourdes Sá de Lira

Universidade Estadual do Piauí, Faculdade de Odontologia

Rua Senador Joaquim Pires 2076 - Ininga

CEP: 64049-590 Teresina, PI, Brasil

E-mail: anadelourdessl@hotmail.com

Received for publication: October 21, 2015

Accepted: December 09, 2015