Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Odontologia Clínico-Científica (Online)

versão On-line ISSN 1677-3888

Odontol. Clín.-Cient. (Online) vol.10 no.2 Recife Abr./Jun. 2011

ARTIGO ORIGINAL / ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Anesthetic blockage of the auriculotemporal nerve and its clinical implications

Bloqueio anestésico do nervo auriculotemporal e suas implicações clínicas

Mirella Marques Mercês do NascimentoI; Gabriela Granja PortoI; Cyntia Medeiros NogueiraII; Belmiro Cavalcanti do Egito VasconcelosIII

I Postgraduate Student of the PhD program in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University of Pernambuco (Recife-Brazil)

II Specialist in Oral Rehabilitation

III Senior Lecturer in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. Director of the Master and PhD programs in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University of Pernambuco (Recife-Brazil)

ABSTRACT

PURPOSE: the aim of this study was to evaluate the use of anesthetic blockage of the auriculotemporal nerve as a treatment for temporomandibular joint disorders. METHODS: the sample comprised of ten patients with temporomandibular disorders classified as group Ia, IIa and IIIa according to the Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders. The blockage of the auriculotemporal nerve was performed with 1 ml of bupivacaine 0.5% without vasoconstrictor for 8 weeks. The maximal mouth opening, jaw protrusion and pain were evaluated at the following time: baseline, 1st week, 8th week and after two months of the treatment. For statistical analysis the F test (ANOVA) was used with a level of significance of 5%. RESULTS: two months after the end of treatment, the anesthetic blockage had decreased the pain, with a significant diff erence (p=0.006). The treatment resulted in an increase in maximal mouth opening (p=0.406) and improved the movement of protusion (p=0.018). CONCLUSION: anesthetic blockage of the auriculotemporal nerve may be used in acute cases of pain in the temporomandibular joint. Therefore the treatment proposed does not seem to be efficacious for reducing pain in temporomandibular joint disorders in a long term follow-up.

Keywords: Temporomandibular Joint, Abnormolities, Nerve block, Anesthetic local.

RESUMO

OBJETIVO: este estudo avaliou o uso de bloqueio anestésico do nervo auriculotemporal como tratamento para disfunções da articulação temporomandibular. METODOLOGIA: amostra foi constituída de dez pacientes com disfunção temporomandibular, classificados nos grupos Ia, IIa e IIIa, de acordo com os Critérios Diagnósticos de Pesquisa em Disfunção Temporomandibular. O bloqueio do nervo auriculotemporal foi realizado com 1ml de bupivacaína a 0,5%, sem vasoconstritor, durante 8 semanas. A máxima abertura de boca, a protrusão da mandíbula e dor foram avaliadas no momento basal, 1ª e 8ª semanas, e após dois meses de tratamento. Para a análise estatística, o teste F (ANOVA) foi utilizado com um nível de significância de 5%. RESULTADOS: dois meses após o término do tratamento, o bloqueio anestésico diminuiu a dor, com uma diferença estatística significativa (p = 0,006). O tratamento proposto resultou em aumento da abertura bucal máxima (p = 0,406) e melhora do movimento de protrusão (p = 0,018). CONCLUSÃO: o bloqueio anestésico do nervo auriculotemporal pode ser utilizado em casos agudos de dor na articulação temporomandibular. Assim, o tratamento proposto não parece ser eficaz para diminuir a dor nos casos de disfunções temporomandibulares a longo prazo.

DESCRITORES: Articulação temporomandibular, Anormalidadedes, Bloqueio nervoso, Anestésicos local.

INTRODUCTION

Temporomandibular disorder (TMD) is a collective term that encompasses masticatory muscle pain, as well as disorders of the tempormandibular joint, including capsulitis, degenerative joint disease, and internal derangement1. It is often characterized by orofacial pain, limited or deviated range-of-motion, joint clicking, and headaches2.

Temporomandibular joint pain and dysfunction are a significant clinical problem for each diverse treatments that have been used. In general, splints have shown modest active therapeutic eff ects in reducing TMD pain, compared to a placebo control in more severe cases, and results comparable to other treatments. Even occlusal treatments are typically irreversible and the evidence of their therapeutic or preventive eff ects on TMD is insufficient3. There is a need for treatments that are reversible, but these need have to be based on a high level of scientific evidence, to be readily available to patients and to have few complications.

Sensory innervation of the temporomandibular joint arises predominantly from the auriculotemporal (AT) nerve with some accessory innervations from the masseteric and deep posterior temporal nerves. The AT nerve arises from the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve and provides most of the sensory input of the TMJ, being an important structure at many painful temporomandibular joint conditions4,5.

The consistent patterns of TMJ innervation suggest that diagnostic nerve blockages can be done to determine the pain pathway in these patients. It is suggested that if the nerve blockage is successful, TMJ denervation may be a future method of pain relief in patients with recalcitrant or recurrent TMJ pain6.

The first technique for the anesthetic blockage of the auriculotemporal nerve was described by Toller7 and was used for arthrography of the temporomandibular joint. Ever since, anesthetic blockage of the auriculotemporal nerve has been used in arthrocentesis, clinical research and diff erential diagnosis8,9,10. The blockage of this nerve is also used for establishing diagnosis for TMJs painful9. It's expected that the anesthetic blockage will diminish the pain leading to a better functional performance of the joint, which enables its nutrition, waste removal and lubrication helping the joint recovery11.

A number of conservative management strategies have been proposed for the treatment of temporomandibular disorders. There is insufficient data in the literature justifying the anesthetic blockage of the auriculotemporal nerve as a treatment for temporomandibular joint disorders. The aim of this case series was therefore to evaluate whether nerve blockage could be an option for the treatment of this pathosis, an inexpensive technique that could alleviate the pain.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Ten patients (all females) were selected for this study. A case series study was carried out at the Center of Clinical Research in Oral-Maxillofacial Surgery at the School of Dentistry of Pernambuco – University of Pernambuco, Brazil from March to December 2009. All participants agreed to answer the questionnaire and signed the term of informed consent. The study received the approval of the Ethics in Research Committee (Process n° CEP/UPE: 177/07 – Registered number CAAE: 0172.0.097.000-07).

The patients were diagnosed with temporomandibular joint disorders using the Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (RDC/TMD)12.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: female and male patients, with a diagnosis of disk displacement (group II) or arthralgia (group IIIa) (RDC/TMD Axis I) disorders and with intensity of pain between 3 and 9 on the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS).

One clinician performed the clinical evaluation and follow-up of each subject in order to ensure the reliability of the clinical diagnosis. This clinician was calibrated for applying RDC/TMD. Another professional made the anesthetic blockage.

The clinical assessment consisted of a standardized evaluation of pain using the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), and the measurements of maximal mouth opening, protrusion and movement to the right and left at the following times: baseline, 1st week, 8th week and two months after the end of treatment (post-treatment).

The patients received the blockage of the auriculotemporal nerve with 1 ml (5mg) of bupivacaine 0.5% without vasoconstrictor (Neocaína 0.5% - Cristália®) for 8 weeks. Injections were made with a 13-mm long needle (diameter 3 mm) and a 3-ml syringe after the skin had been cleaned with alcohol and negative aspiration performed. For the AI nerve block, the TMJ condyle was palpated with the index finger while the patient opened and closed the jaw. Then, the subject was asked to open the mouth wide and the finger followed the contour of the condyle inferiorly until it reached the neck of the condyle, approximately 1-1.5 cm below the tragus7,8. The needle was inserted posteriorly to the mandible at a depth of approximately 13-mm, where the solution was injected.

For data analysis, absolute and percentage distributions were determined for qualitative and numeric variables. The F test (ANOVA) was used with a 5% level of significance.

RESULTS

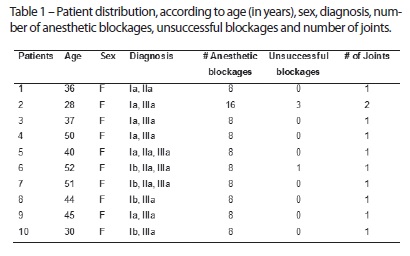

The patients showed ages ranged from 28 to 52 years, with a mean age of 41.3 ± 8.5years. In Table 1 it may be seen that the group Ia (myofacial pain) and group IIIa (arthralgia) disorders were the most frequent, with 6 and 9 cases, respectively. According to the RDC/TMD groups, group I (muscle disorders) represented 100% (10/10 subjects); group II (disk displacement) corresponded to 40% of the sample (4/10 subjects); and group III (arthralgia) accounted for 90% (9/10 subjects).

Eighty-eight anesthetic blockages of the auriculotemporal nerve were performed in 11 joints, of which and 6.8% (6/88) were unsuccessful. The blockage was considered unsuccessful when the patient reported no relief of pain at the joint or numbness of the region, or had the pre-auricular and parotid side not anesthetized (Table 1).

Out of the total of 88 anesthetic blockages, there were 31 cases of facial nerve block (35.2%) and four cases of unsuccessful blockages (4.5%). There was one episode of hematoma (1.1%) and one positive aspiration (1.1%).

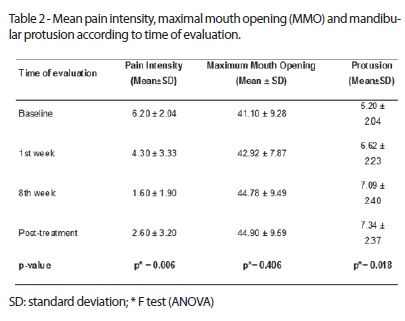

Table 2 shows that there was a significant diff erence between the intensity of pain according to the time of evaluation (p = 0.006). However, the intensity of pain increased after the injections stopped. It also can be seen that the mean MMO ranged from 41.10 to 44.90 mm with no significant diff erences (p> 0.05) in relation to the time of evaluation. The mean mandidular protrusion ranged from 5.20 mm (baseline) to 7.34 (post-treatment), showing a significant statistical diff erence (p=0.018) (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

In the current literature, the auriculotemporal nerve is the main sensory innervation of the TMJ5. The blockage of this nerve was first described by Toller7. Ten years later, Dolon8 employed the blockage in fifty patients (60 joints) submitted to arthrography and artrocenthesis. Subsequently Okeson9 showed that the technique could be used for the diff erential diagnosis in painful TMJs.

In the search for conservative therapies to disorders in the temporomandibular joint, we find that orthopedic techniques are used to block the suprascapular nerve for the treatment of adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder), associated with physiotherapy, when the disease does not respond well to initial treatment, achieving satisfactory results13,14,15,16.

We originally hypothesized that the use of anesthetic blockage of the auriculotemporal nerve would be applied as a treatment for temporomandibular joint disorders since a painless joint may lead to a reestablishment of its function, which enables its nutrition, waste removal and lubrication11.

The RDC / TMD was selected because it has been widely accepted as a research tool for studying TMD and it is also used in clinical trials and epidemiological research. The prevalence of muscle disorders (group I) in the present investigation was observed in all participants, followed by arthralgia (group IIIa) and disc displacement (group II) disorders. The sample was entirely female. The most common type of TMD was muscle disorders which are in agreement with Dworkin17, Yap18, Lee19 and Winocur20. A possible explanation for these results could be that females are more likely to report musculoskeletal pain than men21.

Few complications of nerve's blockage were reported in this study. There were 35.2% cases of temporary facial nerve blockage (31/88) and one episode of hematoma (1.1%) and positive aspiration (1.1%). The studies of Dolon8 showed complications such as subcutaneous hematoma 2% (1/50), zigomaticotemporal paralysis 14% (7/50), orbicular muscle paralysis 24% (12/50) and no positive aspirations. The rate of facial nerve paralysis can be justified by the close contact between this nerve with the auriculotemporal nerve22,23.

A double-blinded, placebo-controlled study assessed the eff ects of local anesthetics on mechanical and thermal sensitivity in the TMJ area10. Twenty-eight healthy subjects without temporomandibular disorders received an auriculotemporal nerve (AT) nerve blockage or an intra-articular (IA) injection with bupivacaine on one side, and a placebo injection of isotonic saline on the contralateral side. Mechanical and thermal sensibilities were assessed at 11 standardized points in the TMJ area. The results showed that the IA injection had no eff ect on the sensitivity of the TMJ or surrounding area, while the AT nerve block had a more pronounced eff ect on deep mechanical sensibility than on the superficial mechanical or thermal sensibility. In addition, the present study explains the behavior of nerve blockage in relation to mechanical sensibility.

In the present study, the authors found a significant decrease in average pain levels during and after treatment. Similarly, these patients did not demonstrate a significant improvement in their ability to achieve maximum mouth opening. The results of treatment with nerve blockage in this study tend to support similar results in the literature, in particular the finding that the manual mobilization with exercises is an eff ective method of pain relief 24.

However, after the suspension of treatment there was a small increase in mean pain. A possible explanation for this finding could be that anesthesia allows the patient to have a better perform of the mandibular movements and increase joint lubrication. The discontinuation of the treatment has already led to return to the beginning of the situation prevailing prior to treatment.

The results of this study suggest that the anesthetic blockage of the auriculotempotal nerve is a technique that may be used in routine clinical practice. It is a noninvasive, low-cost treatment and has a low rate of complications. This means that it may become a tool for the diagnosis and treatment of acute joint pain. More experience and understanding of the technique could lead to better results in the future.

CONCLUSION

The anesthetic blockage of the auriculotemporal nerve may be used in acute cases of pain in the temporomandibular joint, being efficient for the mandibular moviments such as jaw protusion and for decreasing pain in the immediate post-operative period. Therefore it does not seem to be efficacious for reducing pain in temporomandibular joint disorders in a long term follow-up.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This investigation was supported by the FACEPE (Reference code: APQ – 0372-4.02/08) and CNPq (Reference code: 472703/2009-9).

REFERENCES

1. Schiff man EL, Fricton JR, Haley DP, Shapiro BL. The prevalence and treatment needs of subjects with temporomandibular disorders. J Am Dent Assoc. 1990; 120: 295-303. [ Links ]

2. Dimitroulis G. Temporomandibular disorders: a clinical update. BMJ. 1998; 317: 190-4.

3. Fricton J. Current evidence providing clarity in management of temporomandibular disorders: summary of a systematic review of randomized clinical trials for intra-oral appliances and occlusal therapies. J Evid Base Dent Pract. 2006; 6:48-52.

4. Sicher H. Temporomandibular articulation in mandibular overclosure. J Am Dent Assoc. 1948; 36:131-9.

5. Fernandes PRB, Vasconsellos HA, Okeson JP, Bastos RL, Maia MLT. The anatomical relationship between the position of the auriculotemporal nerve and mandibular condyle. Cranio. 2003; 21: 165-71.

6. Davidson JA, Metzinger SE, Tufaro AP, Dellon AL. Clinical implications of the innervation of the temporomandibular joint. J Craniofac Surg. 2003; 14:235-9.

7. Toller PA. Opaque arthrography of the temporomandibular joint. Int J Oral Surg. 1974; 3:17-28.

8. Dolon WC, Truta MP, Eversole LR. A modified auriculotemporal nerve block for regional anesthesia of the temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1984; 42: 544-5.

9. Okeson JP. Bell's orofacial pains. 1st ed. Chicago: Quintessence; 1995.

10. Ayesh EE, Jensen TS, Svensson P. Eff ects of local anesthetics on somatosensory function in the temporomandibular joint area. Exp Brain Res. 2007; 180:715-25.

11. Nitzan DW, Price A. The use of arthrocentesis for the treatment of osteoarthritic temporomandibular joints. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:1154-9.

12. Dworkin SF, LeResche L. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: review, criteria, examinations and specifications, critique. J Craniomandib Disord. 1992; 6:301-55.

13. Jones DS, Chattopadhyay C. Suprascapular nerve block for the treatment of frozen shoulder in primary care: a randomized trial. Br J Gen Pract. 1999; 49: 39-41.

14. Dahan THM, Fortin L, Pelletier M, Petit M, Vadeboncoeur R, Suissa S. Double blind randomized clinical trial examining the efficacy of bupivacaine suprascapular nerve blocks in frozen shoulder. J Rheumatol. 2000; 27:1464-9.

15. Karataş GK, Meray J. Suprascapular nerve block for pain relief in adhesive capsulitis: comparison of 2 diff erent techniques. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002; 83: 593-7.

16. Harmon D, Hearty C. Ultrasound-guided suprascapular nerve block technique. Pain Physician. 2007; 10:743-6.

17. List T, Dworkin SF. Comparing TMD diagnosis and clinical findings at Swedish and US TMD centers using research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders. J Orofac Pain. 1996; 10:240–53.

18. Yap AU, Dworkin SF, Chau EK, List T, Tan BC, Tan HH. Prevalence of temporomandibular disorder subtypes, psychologic distress, and psychosocial dysfunction in Asian patients. J Orofac Pain. 2003; 17:21–8.

19. Lee LT, Yeung RW, Wong MC, McMillan AS. Diagnostic sub-types, psychological distress and psychosocial dysfunction in southern Chinese people with temporomandibular disorders. J Oral Rehabil. 2008; 35:184-90.

20. Winocur E, Steinkeller-Dekel M, Reiter S, Eli I. A retrospective analysis of temporomandibular findings among Israeli-born patients based on the RDC/TMD. J Oral Rehabil. 2009; 36:11-7.

21. Dao TT, LeResche L. Gender diff erences in pain. J Orofac Pain. 2000; 7:169–84.

22. Namking M, Boonruangsri P, Woraputtaporn W, Güldner FH. Communication between the facial and auriculotemporal nerves. J Anat. 1994; 185:421-6.

23. Kwak HH, Park HD, Youn KH, Hu KS, Koh KS, Han SH, Kim HJ. Branching patterns of the facial nerve and its communication with the auriculotemporal nerve. Surg Radiol Anat. 2004; 26:494-500.

24. Carmeli E, Sheklow SL, Bloomenfeld I. Comparative study of repositioning splint therapy and passive manual range of motion techniques for anterior displaced temporomandibular discs with unstable excursive reduction. Physiotherapy. 2001; 87:26-36.

Endereço para correspondência:

Endereço para correspondência:

Prof. Dr. Belmiro Cavalcanti do Egito Vasconcelos

Faculdade de Odontologia de Pernambuco - Universidade de Pernambuco

Av. General Newton Cavalcanti, 1650 Camaragibe – Pernambuco/Brasil CEP: 54753-220

E-mail: belmiro@pesquisador.cnpq.br

Recebido para publicação: 24/02/11

Encaminhado para reformulação: 01/03/11

Aceito para publicação: 10/03/11