Services on Demand

Article

Related links

Share

Odontologia Clínico-Científica (Online)

On-line version ISSN 1677-3888

Odontol. Clín.-Cient. (Online) vol.10 n.4 Recife Oct./Dec. 2011

ARTIGO ORIGINAL / ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Basic knowledge on oral cancer among a specific brazilian population

Conhecimento básico sobre câncer bucal em uma população brasileira específica

Cláudio Rômulo Comunian I; Evandro Neves Abdo II; Lisette Lobato Mendonça III; Marcelo Drummond Naves II

I Mestre em Estomatologia, Faculdade de Odontologia da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais

II Doutor em Estomatologia, Faculdade de Odontologia da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais

III Doutora em Epidemiologia, Faculdade de Odontologia da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais

ABSTRACT

Objective: The aim of this investigation was to research the basic knowledge of oral cancer in a particular population belonging to the University Campus of Minas Gerais, where all individuals under investigation were highly exposed to information in general. Methods: The sample consisted of 260 individuals distributed amongst students, professors and administrative staff. The variables "risk factor", "protective factor", "oral cancer self-examination" and "initial signals on oral cancer" were categorized, scored and graded in order to obtain a better picture of the basic knowledge on oral cancer of that population. Results: The knowledge on oral cancer seems to increase with age and women had a better knowledge than men. Considering that this population was highly exposed to information available in the campus, the level of knowledge on oral cancer found was not at all satisfactory. Conclusion: It shows the need to invest in comprehensive and long-term educational programs about oral cancer, its causes and consequences, as well as how to prevent it.

Keywords: Oral cancer; Risk factors for oral cancer; Oral cancer prevention.

RESUMO

Objetivo: O objetivo desta pesquisa foi avaliar os conhecimentos básicos do câncer bucal em uma população específica do Campus Universitário de Minas Gerais, onde todos os indivíduos sob investigação são mais expostos à informação em geral. Métodos: A amostra consistiu de 260 indivíduos distribuídos entre os estudantes, professores e pessoal administrativo. As variáveis "fator de risco", "fator protetor", "autoexame para câncer bucal" e "primeiros sinais de câncer bucal" foram categorizadas, pontuadas e classificadas, a fim de se obter uma melhor imagem do conhecimento sobre câncer bucal dessa população. Resultados: O conhecimento sobre câncer bucal parece aumentar com a idade, tendo as mulheres um melhor conhecimento que os homens. Considerando que essa população é mais exposta às informações disponíveis no campus, o nível de conhecimento sobre câncer bucal encontrado não foi de todo satisfatório. Conclusão: Os resultados mostram a necessidade de investimento a longo prazo em programas educativos mais abrangentes sobre o câncer bucal, suas causas e consequências bem como a forma de se evitá-lo.

Descritores: Câncer bucal; Fator de risco para o câncer bucal; Prevenção do câncer bucal.

INTRODUCTION

Oral cancer is a serious problem in Brazil. Between 1980 and 1998, the mortality rate due to oral cancer in Sao Paulo was high and little evidence of a political for reverse the situation was observed1. Another alarming fact is the increase of oral cancer cases, regardless of gender, according to the National Cancer Institute (INCA) .2

The early diagnosis of oral cancer plays an important role in patient survival's rate. However studies showed that oral cancer is only diagnosed in advanced stages. 3,4,5,6,7,8 Furthermore, even dentists and hygienists, who are expected to have better knowledge about this issue, present gaps of certain risk factors.4

The knowledge about risk factor on oral cancer is important to establish educational programs as well as to provide a better prognosis and reductions in treatment cost.6,9,10 Studies show that individuals with low education and socio-economic level have poor knowledge about oral cancer.11,12,13,14

The premise of the present study is that a well-educated population, with high level of education, have better basic knowledge on oral cancer than those with low educational level. Therefore, the aim of this investigation was to investigate basic knowledge of oral cancer of a particular population belonging to the Federal University of Minas Gerais.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The present study was carried out at the campus of the Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil. The variables under investigation were: gender, age, professional activity, schooling level, family income, information about oral cancer, source of information about oral cancer, information about oral cancer self-examination, in the case of perceiving a sign of oral cancer which the professional would be consulted, and specific knowledge about oral cancer: risk factors , protective factor and initial signs.

The sample consisted of 260 individuals attending campus activities either as professors or students or administrative staff. All individuals were 18 years of age or older and able to answer the questionnaire by themselves. The questionnaires were filled between October and December 2003 within the campus area.

The variables "risk factor", "protective factor", "oral cancer auto-examination" and "initial signs on oral cancer" were categorized, scored and graded to obtain a better picture of the basic knowledge on oral cancer of this population.

The following levels of knowledge were established:

• 1 to 3 points = low knowledge

• 4 to 6 points = regular knowledge

• 7 to 9 points = intermediate knowledge

• 10 to 12 points = good knowledge

• 13 to 15 points = excellent knowledge.

The statistical program used was SAS and the results were tested with Chi-square and Fisher test. The analysis of the influence of all variables on the level of knowledge was performed using the Kruskal-Wallis test for two groups, and Mann-Whitney for three or more groups. The Ethical Committee from the Federal University of Minas Gerais approved the study (ETIC 082/03).

RESULTS

The sample was categorized as such: 14% Professors, 69% students (grads and undergrads), 17% administrative staff, reflecting the campus population distribution itself.

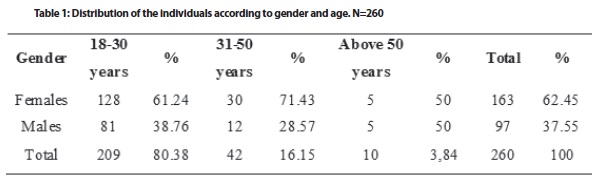

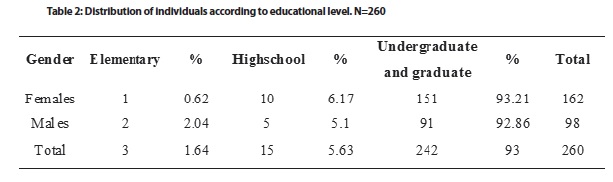

The sample as depicted consisted largely by females (62.45%), young adults (80.38%) and undergraduate and graduate. (93.5%). (Table 1 and 2)

Those individuals with academic experience (students and Professors) belonged to following areas: 38.3% bioscience and health science, 27.6% exact science and engineer, 34.1% social, human science and art and literature.

The distribution of family income showed that 20% of the sample had high income (more than 10 minimum wages) and 26% low income (less than 10 minimum wages).

88.9% mentioned that had some knowledge on oral cancer, and that information was mostly obtained from written media followed by TV and health professionals. Amongst those, only 17.3% of subjects had been informed about oral self-examination.

The variables gender, age, activity at work, schooling level and family income did not seem to influence the knowledge about oral cancer. However, it is interesting to observe that women had more information on oral cancer than men, especially those between 31 and 50 years old. The fact of being a student, professor or University worker did no influence their knowledge about oral cancer. One would expect better knowledge about oral cancer from individuals working with bioscience or health science in comparison to another areas, or between grads and undergrads students, or even between professors (89.3%) and workers who did not finished college (81.3%).

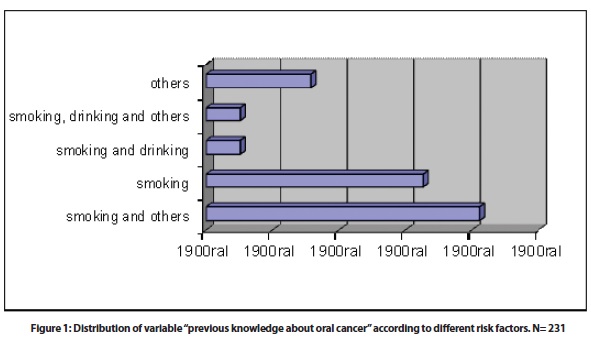

Many considered smoking as the major risk factor for oral cancer. Nevertheless, most of the individuals associated oral cancer with smoking and other habits. The majority of individuals did not consider the association smoking and alcohol or alcohol alone as an important risk factor for oral cancer, as depicted in figure 1.

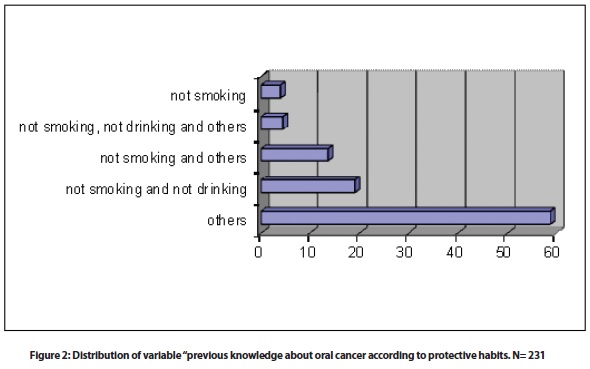

When asked about the factors that might protect against oral cancer, only a small number of individuals pointed not smoking as important. Only 19.1% considered not drinking and not smoking important to protect against oral cancer. More than a half of the sample (58.8%) considered a set of non relevant habits important in oral cancer, as shown in figure 2.

Most of the individuals (85.7%) knew at the most 2 initial signs of oral cancer. In case of any initial detection lesion they would look for a dentist for proper diagnosis (58.9%) and only 22% would go after a medical doctor and 19% would look for both professionals.

It was not possible to find more than 34.6% of individuals with a good "basic knowledge about oral cancer". From the whole sample, only 42% showed a regular knowledge and only 34.6% had an intermediate knowledge on oral cancer.

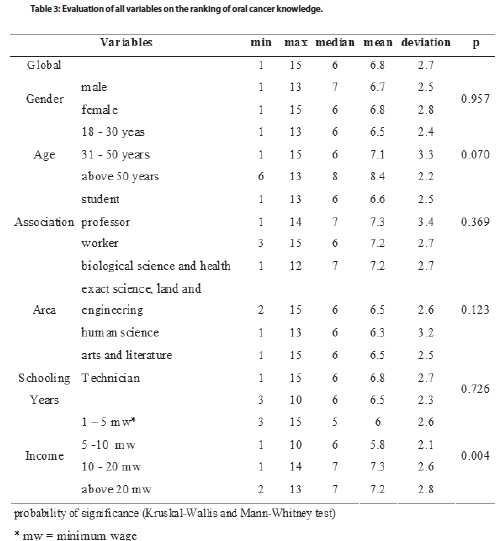

From all variables studied as possible interference on the oral cancer basic knowledge, only the family income showed a statistical importance. Those individuals receiving less than 10 mw (1 minimal wage= 130USD) did show a significant lower knowledge about oral cancer than those with higher family income (p=0.004).

Although not statistically significant, age did present a tendency to be associated to knowledge on oral cancer, since individuals older than 51 years of age showed a better knowledge on oral cancer than the younger ones (p=0.07), as detailed in Table 3.

DISCUSSION

The Results indicate that everyone that's working or studying at the University are similarly exposed to oral cancer knowledge.

The population under investigation has unique characteristics which differentiates it from the rest of society. It is a University Campus and although people from different social economic background belong to it, they are all in some extend exposed to information in similar ways and amount.

The knowledge about oral cancer in this study showed only a borderline risk factor association between smoking and oral cancer. Nevertheless the findings here are similar to other studies 10-12. It should be pointed out that the populations under those studies were more heterogeneous than the one of the present study, where a stronger association between smoking and oral cancer risk was expected. Table 3: Evaluation of all variables on the ranking of oral cancer knowledge.

Concerning the variable alcohol consumption and oral cancer, the results showed a low level of association. In other studies, the range of association between alcohol drinking and oral cancer ranged from of 16% to 45%.10,11,12,15

Although alcohol consumption and smoking are worldwide recognized as major risk factors for oral cancer, the relationship between smoking and many other health conditions is vastly spread by the media. That is not the case of alcohol drinking. The media associates the consumption of alcohol only with risk of traffic accident. That could explain why people in general associate more oral cancer with smoking than with alcohol drinking.

The results here presented suggest that knowledge on oral cancer was higher in individuals over 51 years of age, which goes against other results showing that knowledge on oral cancer was less in older individuals.11,16 This could be explained by the fact that the older individuals in our sample were Professors, naturally holding more and differentiated information about the matter under investigation.

Another parameter that played a strong role on the knowledge of oral cancer was the family income. Individuals with lower income showed less knowledge about oral cancer. This is consistent with other results showing strong relationship between socio economic level and access to information.15,19

It seems to be cultural the fact that individuals seek, at first, a medical doctor when their oral problem is not dental caries or gum disease.12,14,15,17,18 On the contrary, the data here presented indicated that the majority of the individuals would seek indeed a dentist if they noticed a suspicious lesion in their mouth. However, that could indicate a bias since they were aware that the interviewer was a dentist.

A better knowledge about oral cancer was expected in this particular population naturally more exposed to information. Epidemiologically, the level of education has a direct role in patient's oral cancer knowledge 5,20,21,22 . But the results here did not support that. Perhaps the poor knowledge about oral cancer is not only related to schooling years but also with the quality and impact of oral cancer campaign in whole society as part of a solid public health policy on oral cancer prevention. As demonstrated by other authors 23,24 who studied breast cancer in Brazil, another assumption should be considered to understand this problem.

Probably, the population under study in the present investigation is more concerned with the specific information related to its specific area of work. Probably the prevailing oral cancer prevention public campaign in Brazil has not been achieving its goal.

An increase of information on oral cancer does not necessarily raise awareness of the disease amongst individuals. As far as health promotion is concerned, that health messages on cancer in general may be more relevant for young people since they are not yet affected by the disease 24,25. Perhaps this reasoning can be applied to the oral cancer prevention campaigns.

To reverse the situation of poor knowledge about oral cancer one should expect a change in amount and quality of public health prevention programs. The impact of such public health campaign must consider an expansion of awareness and self care. Finally, there is also a need for a systematic campaign on risk of oral cancer and the implementation of a system that can mobilize health professionals in earlier detection of primary oral lesions to allow diagnose of oral cancer in its initial phase.

CONCLUSION

Family income was the only variable to play a role on oral cancer basic knowledge. Those individuals receiving less than 10 mw (1 minimal wage= 130USD) did show a significant lower knowledge on oral cancer than those with higher family income (p=0.004).

The association smoking and alcohol or alcohol alone was not considered an important risk factor for oral cancer. Only 19.1% considered not drinking and not smoking important to protect against oral cancer. More than half of the sample (58.8%) considered a set of non relevant habits important in oral cancer.

REFERENCES

1. Antunes JLF, Biazevic MGH, de Araújo ME, Tomita NE, Chinellato LE, Narvai PC. Trends and spatial distribution of oral cancer mortality in São Paulo, Brazil, 1980-1998. Oral Oncol. 2000; 37(4):345-50. [ Links ]

2. Instituto Nacional de Câncer. Estimativas/2006. Incidência de Câncer no Brasil. Available: http://www.inca.gov.br/estimativas/ 2006. (Assessed 2007 March 11).

3. Onizawa K, Nishihara K, Yamagata K, Yusa H, Yanagawa T, Yoshida H. Factors associated with diagnostic delay to oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2003; 39(8): 781-88.

4. Gajendra S, Cruz GD, Kumar JV. Oral cancer prevention and early detection: Konwledge, practices and opinions of oral care providers in New York State. J Cancer Educ. 2006, 21(3):157-62.

5. Leite ICC, Koifman S. Survival analysis in a sample oral cancer patients at references hospital in Rio de Janeiro- Brazil. Oral Oncol. 1998; 34(5):347-52.

6. Kerdpon D, Sriplung H. Factors related to advanced stage oral squamous cell carcinoma in southern Thailand. Oral Oncol. 2001; 37(3):216-21.

7. Carvalho AL, Pintos J, Schlecht NF, Oliveira BV, Fava AS, Curado MP, et al. Predictive factors for diagnosis of advanced-stage squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002; 128(3):313-31

8. Abdo EN, Garrocho AA, Barbosa AA, Oliveira EL, França-Filho L, Negri SL, et al. Time elapsed between the first symptoms, diagnosis and treatment of oral cancer patients in Belo Horizonte, Brazil. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2007; 12(7): E469-73.

9. Lowry RJ, Craven MA. Smokers and drinkers awareness of oral cancer: a qualitative study using focus groups. Br Dent J. 1999; 187(12):668-70.

10. Horowitz AM, Nourjah P, Gift HC. U.S. adult knowledge of a risk factors a signs of oral cancer: 1990. J Am Dent Assoc. 1995; 126(1):39-45.

11. Gomes AV, Carvalho EM. O conhecimento da população sobre prevenção do câncer no Brasil. Rev Bras Cancerol. 1999; 45(3):29-37.

12. Cruz GD, Le Geros RZ, Ostroff JS, Hay JL, Kenigsberg H, Franklin DM. Oral cancer knowledge, risk factors and characteristics of subjects in a large oral cancer screening program. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002; 133(8):1064-71.

13. Horowitz AM, Canto MT, Child WL. Maryland adult´s perspective on oral cancer prevention and early detection. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002; 133(8):1058-63.

14. Warnakulasuriya KA, Harris CK, Scarrot DM, Watt R, Gelbier S, Peters TJ, et al. An alarming lack of public awareness towards oral cancer. Br Dent J. 1999; 187(6):319-22.

15. Shetty KV, Johnson NW. Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of adult South Asian living London regarding risk factors and signs for oral cancer. Community Dent Health. 1999; 16(4):227-31.

16. Fabian MC, Irish JC, Brown DH, et al. Tobacco, alcohol and oral cancer: the patient´s perspective. J Otoloryngol 1996; 25(2):88-93.

17. Humphris GM, Field EA. The immediate effect on knowledge, attitudes and intentions on primary care attenders of a patient information leaflet: a randomized control trial replicaton an extension. Br Dent J. 2003;194(12):683-88.

18. Hashibe M, Jacob BJ, Thomaz G, et al. Socio economic status, lifestyle factors and oral premalignant lesions. Oral Oncol. 2003; 39(7):664-71.

19. Canto MT, Horowitz AM, Child WL. Views on oral cancer prevention and early detection: Maryland physicians. Oral Oncol. 2002; 38(4):373-77.

20. Abdo EN, Garrocho AA, Aguiar MCF. Avaliação do nível de informação dos pacientes sobre o álcool e o fumo como fatores de risco para o câncer bucal. Rev ABO Nac. 2006; 14(1):44-48.

21. Petit E, O´Shea R, Greene G. Dentist and oral cancer: the experience and attitudes of the practiones. N Y States Dent. 1976; 42(3):161-67.

22. Franco EL, Kowalski LP, Oliveira BV, Curado MP, Pereira RN, Silva ME, et al. Risk factors of oral cancer in Brazil: a case-control study. Int J Cancer. 1989; 43(6):992-1000.

23. Freitas Jr. R, Koifman S , Santos NR, Nunes MO, de Melo GG, Ribeiro AC, et al. Knowledge and practice of breast self-examination in Goiania. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2006; 52(5):337-41.

24. Petit S, Scully C. Oral cancer knowledge and awareness: primary and secondary effects of an information leaflet. Oral Oncol. 2007; 43(4):408-15.

25. Peacey V, Steptoe A, Davidsdottir S, Baban A, Wardle J. Low levels of breast cancer risk awareness in young women: an international survey. Eur J Cancer. 2006; 42(15):2585-89.

Endereço para correspondência:

Endereço para correspondência:

Prof. Evandro Neves Abdo

Faculdade de Odontologia da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais

Avenida Antônio Carlos, 6627 – Pampulha

Belo Horizonte/Brasil CEP: 31270-901

E-mail: evandro.abdo@gmail.com

Recebido para publicação: 26/07/11

Aceito para publicação: 27/10/11