Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

Revista Odonto Ciência (Online)

versão On-line ISSN 1980-6523

Rev. odonto ciênc. (Online) vol.25 no.4 Porto Alegre Out./Dez. 2010

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Harmful oral suction habits in children: association with breastfeeding and family social profile

Hábitos bucais de sucção deletérios em crianças: associação com padrão de aleitamento e perfil social familiar

Suzely Adas Saliba MoimazI; Luiz Fernando LolliII; Cléa Adas Saliba GarbinI; Orlando SalibaI; Nemre Adas SalibaI; Poliane da Silva AzevedoIII

IDepartment of Pediatric and Social Dentistry, UNESP Sao Paulo State University, Aracatuba, SP, Brazil

IIPreventive and Social Dentistry Graduate Program, UNESP Sao Paulo State University, Aracatuba, SP, Brazil

IIIDental School, UNESP Sao Paulo State University, Aracatuba, SP, Brazil

ABSTRACT

PURPOSE: To record the prevalence of nonnutritive sucking habits (thumb and pacifier sucking) in children at 6 and 12 months of age and test its association with family social profile and breastfeeding pattern.

METHOD: The sample consisted of 80 pairs of mother-child living in the Northwest region of the state of São Paulo, Brazil. A semi-structured questionnaire was used to collect data on the presence of nonnutritive sucking habits, family social profile and breastfeeding pattern when the children had 6 and 12 months of age. Data were analyzed by using qui-square tests.

RESULTS: Pacifier sucking was more frequent than thumb sucking. Exclusive breast feeding was not reported for children either in the 6th or 12th month of age, and approximately 70% were already receiving artificial feeding. There was no association between family social profile and sucking habits, but lower rates of breastfeeding was associated with pacifier sucking in the 12-month old children. Thumb sucking was not associated with breastfeeding.

CONCLUSION: The frequency of breastfeeding was lower than that recommended by WHO for children in the age groups assessed. Pacifier sucking was more prevalent than thumb sucking and was associated with a lower rate of breastfeeding in the 12th-month old children. Family social profile does not seem to be related with nonnutritive sucking habits.

Key words: Breast feeding; sucking habits

RESUMO

OBJETIVO: Registrar o padrão de aleitamento materno, o padrão familiar social e os hábitos de sucção deletérios (chupeta e dedo) em crianças com 6 e 12 meses de idade e testar a associação desses fatores.

METODOLOGIA: A amostra foi composta por 80 pares de mãe-criança, residentes da região do noroeste do estado de São Paulo, Brasil. Utilizou-se um questionário semi-estruturado para a coleta de dados de presença ou não de hábito de sucção de chupeta e/ou dedo, tipo de aleitamento e padrão familiar social quando as crianças tinham 6 e 12 meses de idade. Os dados foram analisados estatisticamente por testes qui-quadrado.

RESULTADOS: Nenhuma criança esteve sob aleitamento materno exclusivo ao 6º e ao 12º mês de idade; 69% já estavam recebendo aleitamento artificial. Mais da metade da amostra (n=52) relatou ao menos um hábito de sucção deletério, sendo que a chupeta foi mais prevalente que a sucção digital. Houve associação entre menor taxa de aleitamento ao 12º mês e sucção de chupeta, mas a sucção digital não interferiu no aleitamento materno.

CONCLUSÃO: O padrão de aleitamento materno esteve abaixo do recomendado pela OMS para o período correspondente. A sucção de chupeta foi mais prevalente que a digital e ao 12º mês esteve associada à menor taxa de aleitamento materno.

Palavras-chave: Aleitamento materno; hábitos de sucção

Introduction

Breastfeeding is important to reduce child mortality, providing nutritional, immunological, economic, ecological and psychological benefits to the children and their families (1). Breastfeeding is also related with the good health of the stomatognathic system because of the correct establishment of nasal breathing, prevention of the onset of deleterious habits and stimulus to the normal development of the entire craniofacial complex (2). For these reasons, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends exclusive breastfeeding for children until six months of age and supplementary breastfeeding until two years of age or more (3).

Sucking during breastfeeding promotes the proper development of the oral cavity and its related anatomical structures regarding mobility, strength, posture, and the adequate functional development of breathing, chewing, swallowing and phonetics, as well as reduces the adoption of nonnutritive sucking habits (4-5). In general, the sucking oral habits can be divided into normal and deleterious habits. The normal sucking habits occur during breastfeeding, movements of the lips, chewing, swallowing and speech, and contribute to the development of a normal occlusion and facial growth. Deleterious oral sucking habits include the use of pacifiers, thumb and other objects, which may contribute to impair occlusion and craniofacial development depending on the frequency, intensity and duration of the oral movement, individual predisposition and age, affecting the child health ultimately (6,7).

Among the harmful sucking habits, the pacifier is widely used by young children in many parts of the world in spite of the contrary recommendations by the WHO and the American Academy of Pediatrics (8). Children who use a pacifier suck less their mother's breast, causing a decrease in milk production and affecting the breastfeeding process as the variety of nozzles may confuse the infant (9). As for thumb or finger sucking, there are few reports on the influence of this habit on breastfeeding.

This study aimed at assessing the prevalence of pacifier and thumb/finger sucking habits in children at the ages of 6 and 12 months and testing the possible association between the mother-family social profile and the child breastfeeding pattern.

Methods

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee on Humans, Faculty of Dentistry of Araçatuba, FOA-UNESP, Araçatuba, SP, Brazil (Protocol number 01471/2006). This work is part of a larger research project entitled "Impact of primary care actions on breastfeeding practice and mother-child oral health", carried out researchers from the Department of Social and Pediatric Dentistry, Faculty of Dentistry of Araçatuba – UNESP, Araçatuba, SP, Brazil. Initially, the sample comprised subjects enrolled from the records of the SIS-Pre-Natal Program in the cities of Birigui and Piacatu, in the northwestern region of São Paulo State, Brazil. All pregnant women enrolled in 2006 (n=150) were invited to participate in the longitudinal study, and 119 were selected and signed an informed consent form. The present study sample consisted of 80 pairs of mother-child from the large sample. Data were collected when the children were 6- and 12-month old.

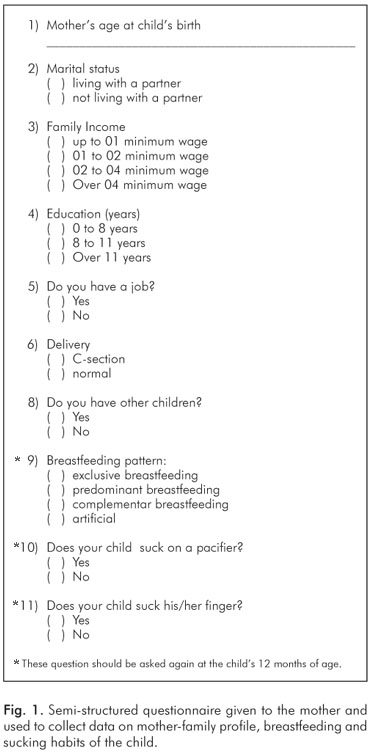

A semi-structured questionnaire (Fig. 1) was developed containing mother-family variables such as age, marital status, education, labor, delivery type, family income and previous children. The variables of interest for the present study were "feeding pattern" and "digital and pacifier sucking habits". This instrument was validated in a pilot study with five mothers attending the clinics for pregnant women at the Community Health Research Center (NEPESCO), at FOA-UNESP.

Data were collected by a single examiner during home visits to the families when the children had 6 and 12 months of age. On the first visit, the mothers were questioned about their maternal and family variables. On both visits they were questioned about the feeding methods given to the child. Breastfeeding was recorded according to World Health Organization (WHO) criteria: exclusive breastfeeding when the child consumes only breast milk, predominant breastfeeding when liquids other than milk are given, supplementary feeding for infants who consume other foods and also breast milk, and finally, artificial feeding when there is total weaning. In addition, mothers were also questioned if their babies had the habit of thumb and pacifier sucking at that time.

Data were analyzed by chi-square tests at the significance level of 5% using the Bioestat 5.0 software (10). Feeding pattern was categorized as breastfeeding (when natural breastfeeding took place, whether exclusive, predominant or supplementary) and artificial/bottle feeding (in the absence of breast milk) for statistical analysis. For mother-family profile, age was categorized into "up to 20 years old" and "over 20 years old". For marital status, the categories were "living with a partner" and "not living with a partner". Family income was categorized into "up to 01 minimum wage", "from 01 to 02 minimum wages" and "above two minimum wages". Maternal education categories were "0-8 years", "8-11 years" and "over 11 years". Statistical analysis was carried out with the Bioestat 5.0 software (10).

Results

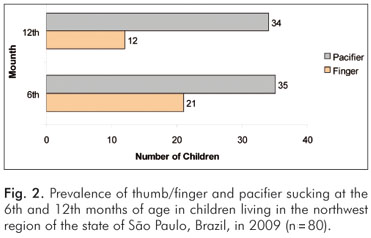

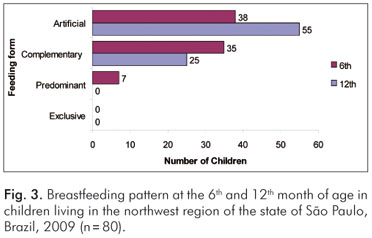

Figure 2 shows the prevalence of thumb/finger and pacifier sucking habits. Figure 3 shows the Pacifier sucking was more frequent than thumb sucking. Exclusive breast feeding was not reported for children either in the 6th or 12th month of age, and approximately 70% were already receiving artificial feeding. feeding patterns of children at 6 and 12 months of age.

The results of the association assessment between mother-family social profile and harmful oral habits are shown in Table 1. Table 2 displays the association between feeding pattern and pacifier and thumb sucking. There was no association between family social profile and sucking habits, but lower rates of breastfeeding was associated with pacifier sucking in the 12-month old children. Thumb sucking was not associated with breastfeeding.

Discussion

This study showed that the frequency of breastfeeding was lower than that recommended by WHO for children at 6 and 12 months of age. Pacifier sucking was more prevalent than thumb sucking and was associated with a lower rate of breastfeeding in the 12th-month old children. Family social profile were not related with nonnutritive sucking habits. Kronborg and Væth (11) also found no association between the use of pacifier and socio-demographic variables. However, Moimaz et al. (12) showed that both digital and pacifier sucking were associated with maternal marital status, and the presence of parents was positively associated with higher prevalence of sucking habits.

Overall, more than half of the children (n=52) had the habit of thumb/finger sucking, pacifier sucking or both. Pacifier sucking was more constant and exceeded finger-sucking for both months of analysis. Our results corroborate those reported by Albuquerque et al. (13), who found that the prevalence of finger sucking was lower than of pacifier use. However, thumb/finger sucking was reported to be more prevalent in other studies suggesting that the habit may depends on the cultural values (14,15). A longitudinal study in the U.S. showed that pacifier sucking was more common among children from birth to 30 months of age. From 30 to 96 months (8 years old) the children had higher prevalence of thumb/finger sucking (16).

Pacifiers are often used worldwide to calm and sooth children (17). Most studies show an association between pacifier use and early weaning, but they did not establish causality. Others raised the hypothesis that the use of pacifiers may be an indicator of a mother's difficulties to breastfeed her child (17,18). Furthermore, the pacifier use has been contraindicated due to its harmful effects on children's oral health, especially because of dental and speech development problems such as malocclusion changes and alterations in breathing, chewing, swallowing and speech functions (19).

A qualitative study on pacifier use examining the mothers' social profile found that the mothers are usually warned about the potential harmful effects caused by the use of pacifiers. However, since pacifiers are affordable and useful to sooth their babies, the mothers often end up offering them to their children (20). Besides the soothing effect, mothers also argue that pacifiers can replace or complement their care to the children when they need something to suction or even help with the breastfeeding schedule (21). A study showed a positive association between mothers who themselves had harmful habits in their childhood and the presence of these same habits in their children (22).

The feeding pattern of children in the present study was found to be different from what is recommended by WHO: no exclusive breastfeeding was reported in children at 6 months of age. Moreover, at the 12 months of age, 69% of the children had already been totally weaned. Saliba et al. (23) found opposite results of exclusive breast feeding: 75% at six months of age and 22% at 12 months for children living in the same northwest region of São Paulo state. In Iran, Koosh et al. (24) found a breastfeeding rate above 90% in the first year of life; however, exclusive breastfeeding was low (44%) in the first month. In the U.S., approximately 73% of mothers initiate breastfeeding in the immediate postpartum period, but only 39% and 20% persisted after the first 6 months and 12 months, respectively (25). According to Lauer et al. (26), the average prevalence of breastfeeding for children up to 6 months of age in 94 developing countries was 39% and the absence of breastfeeding was 5.6%. This shows that, although breastfeeding benefits are known, mainly from exclusive breastfeeding, its prevalence is low prevalence in different parts of the world.

When evaluating the association between sucking habits and feeding patterns, it was observed that children on artificial feeding at the age of 12 months showed a higher habit of pacifier use compared to breastfed children (exclusive + predominant + supplementary). On the other hand, breastfeeding patterns were not statistically associated with thumb sucking. Similar results were described by Moimaz et al. (12): breastfeeding was negatively associated with pacifier use and had no association with thumb sucking. Leite-Cavalcanti et al. (27) showed that about 80% of children with artificial feeding had one or more oral habits, while those who were breastfed showed only 18%. It is worth mentioning that they also found that children breastfed for a period not exceeding six months had a higher frequency of malocclusion (82%) compared with those who were breastfed for a period of not less than 19 months (46%).

Kroeff de Souza et al. (7) found that children who had never been breastfed or who had had mixed feeding before three months of age were about seven times more likely to develop sucking habits than children who were breastfeed for three or six months. When studying the causal effect on early weaning up to three months of age, Benis (17) found that pacifier use may be an early indicator of trouble or even lack of motivation of the mother to breastfeed her child, as causality opposition to weaning. Kromborg and Vaeth (11) associated the pacifier use to a shorter duration of exclusive breastfeeding, and its use should be avoided in the first weeks after birth by mothers who want to breastfeed.

Most studies carried out on the breastfeeding and pacifier use identify two pathways: on the first, pacifiers seem to be a cause or a determinant of weaning in breastfed children; on the second, pacifiers are seen as a consequence or indicator of breastfeeding problems (18). Given this, the question remains: would the pacifier be a weaning determinant or an alternative for situations where weaning occurs due to other causes? These aspects should be further studied. Although it was not the focus of this study, it is worth mentioning that both the low rate of breastfeeding and thumb/finger and pacifier sucking have been historically associated with high rates of children malocclusion in the subsequent years (2,6,27) and, thus, these practices deserve special attention from parents and dental professionals.

Conclusion

Breastfeeding frequency was considered low in the present sample considering the WHO recommendations for the children age. Over half the sample reported some harmful sucking habits. Pacifier sucking was more prevalent than thumb/finger sucking. At 12 months of age, children who were artificially fed made use of pacifiers more frequently than those who were breastfed, which reinforces the importance of breastfeeding to prevent harmful oral habits. However, this study found no association between thumb/finger sucking and breastfeeding.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Coordination of Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) for their support to our research.

References

1. Binns CW, Fraser ML, Lee AH, Scott J. Defining exclusive breastfeeding in Australia. J Paediatr Child Health 2009;45:174-80. [ Links ]

2. Trawitzki LV, Anselmo-Lima WT, Melchior MO, Grechi TH, Valera FC. Breast-feeding and deleterious oral habits in mouth and nose breathers. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 2005;71:747-51. [ Links ]

3. World Health Organization. The optimal duration of exclusive breast feeding: a systematic review. [Accessed on 2009 Nov 12]. Available at http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/WHO_NHD_01.08/en/index. [ Links ]html.

4. Chaves AMB, Colares V, Rosenblatt A, Oliveira AFB. The influence of early weaning on development of non-nutritive sucking habits. Arq Odontol 2002; 38:327-35. [ Links ]

5. Lau C. Development of oral feeding skills in the preterm infant. Arch Pediatr 2007; 14:S35-41. [ Links ]

6. Silva Filho OG, Cavassan AO, Rego MVNN, Silva PRB. Sucking habits and malocclusion: epidemiology in deciduos dentition. Rev Clin Ortodontia Dental Press 2003; 2:57-74. [ Links ]

7. Souza DFRK, Valle MAS, Pacheco MCT. Clinical relationship among suction oral habits, malocclusion, infant feeding and mother's previous knowledge. Rev Dent Press Ortodon Ortopedi Facial 2006;11:81-90. [ Links ]

8. Aznar T, Galán AF, Marin I, Domínguez A. Dental arch diameters and relationships to oral habits. Angle Orthod 2005; 76:441-5. [ Links ]

9. Scott JA, Binns CW, Oddy WH, Graham KI. Predictors of breastfeeding duration: evidence from a cohort study. Pediatrics 2006;117:646-55. [ Links ]

10. Ayres M, Ayres Júnio M, Ayres DL, Santos AA. Bioestat: statistical applications in the areas of bio-medical sciences. Belém: Ong Mamiraua; 2007. [ Links ]

11. Kronborg H, Væth M. How are effective breastfeeding technique and pacifier use related to breastfeeding problems and breastfeeding duration? Birth 2009;36:34-42. [ Links ]

12. Moimaz SA, Zina LG, Saliba NA, Saliba O. Association between breast-feeding practices and sucking habits: a cross-sectional study of children in their first year of life. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent 2008;26:102-6. [ Links ]

13. Albuquerque SSL, Duarte RC, Cavalcanti AL, Beltrão, EM. The influence of feeding methods in the development of nonnutritive sucking habits in childhood. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva 2010;15:371-8. [ Links ]

14. Solis CEM, Rosado JFC, Rosado AJC. Malos hábitos orales en infantes de guarderías del IMSS. Rev Med IMSS 2001; 39: 435-40. [ Links ]

15. López Del Valle LM, Singh GD, Feliciano N, Machuca M del C. Associations between a history of breast feeding, malocclusion and parafunctional habits in Puerto Rican children. P R Health Sci J 2006;25:31-4. [ Links ]

16. Bishara SE, Warren JJ Broffitt B, Levyd SM. Changes in the prevalence of nonnutritive sucking patterns in the first 8 years of life. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2006; 30:31-6. [ Links ]

17. Benis MM. Are pacifiers associated with early weaning from breastfeeding? Adv Neonatal Care 2002; 2:259-66. [ Links ]

18. Araújo CMT, Silva GAP, Coutinho SB. Breastfeeding and pacifier use: repercussions on feeding and on oral motor sensory system development. Rev Paul Pediatr 2007;25:59-65. [ Links ]

19. Kramer MS, Barr RG, Dagenais S, Yang H, Jones P, Ciofani L, Jané F. Pacifier use, early weaning, and cry/fuss behavior: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001; 286:322-6. [ Links ]

20. Marques ES, Cotta RMM, Araújo RMA. Social representations of women who brasfeed about breast feeding and the use of pacifiers. Rev Bras Enferm 2009;62:562-9. [ Links ]

21. Sertório SC, Silva IA. The symbolic and utilitarian facets of pacifiers according to mothers. Rev Saúde Pública 2005; 39:156-62. [ Links ]

22. Serra-Negra JMC, Vilela LC, Rosa AR, Andrade ELSP, Paiva SM, Pordeus IA. Deletery oral habits: do children imitate their mothers when adopt these habits? Rev Odonto Cienc 2006;21: 146-52. [ Links ]

23. Saliba NA, Zina LG, Moimaz SAS, Saliba O. Frequency and associated variables to breastfeeding among infant up to 12 months of age in Araçatuba, State of São Paulo, Brazil. Rev Bras Saúde Matern Infant 2008; 8:481-90. [ Links ]

24. Koosha A, Hashemifesharaki R, Mousavinasab N. Breast-feeding patterns and factors determining exclusive breast-feeding. Singapore Med J 2008;49:1002-6. [ Links ]

25. Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, Martin JA, Sutton PD. Preliminary births for 2004: Health E-stats. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2005. [ Links ]

26. Lauer JA, Betrán AP, Victora CG, De Onís M, Barros AJD. Breastfeeding patterns and exposure to suboptimal breastfeeding among children in developing countries: review and analysis of nationally representative surveys. BMC Medicine 2004; 2:1-29. [ Links ]

27. Leite-Cavalcanti A, Medeiros-Bezerra PK, Moura C. Breast-feeding, bottle-feeding, sucking habits and malocclusion in Brazilian preschool children. Rev Salud Publica 2007; 9:194-204. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Luiz Fernando Lolli

Universidade Estadual Paulista Júlio de Mesquita Filho

Faculdade de Odontologia de Araçatuba

Departamento de Odontologia Social

Rua José Bonifácio, 1193 – Vila Mendonça

Caixa-Postal: 341

Araçatuba, SP – Brasil

16015050

E-mail: profluizodontologia@uol.com.br

Received: December 1, 2009

Accepted: August 26, 2010

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors state that there are no financial and personal conflicts of interest that could have inappropriately influenced their work.