Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

RGO.Revista Gaúcha de Odontologia (Online)

versão On-line ISSN 1981-8637

RGO, Rev. gaúch. odontol. (Online) vol.59 no.1 Porto Alegre Jan./Mar. 2011

ORIGINAL ORIGINAL

Incidence of Entamoeba gingivalis and Trichomonas tenax in samples of dental biofilm and saliva from patients with periodontal disease

Incidência de Entamoeba gingivalis e Trichomonas tenax em amostras de biofilme e saliva de pacientes com doença periodontal

Ricardo Luiz Cavalcanti de Albuquerque JúniorI,*; Cláudia Moura de MeloI; Wagno Alcântara de SantanaI; Juliana Lopes RibeiroII; Flávia Albuquerque SilvaII

IPos-Graduation Program in Health and Environment, University Tiradentes. Av. Murilo Dantas, 300, Farolândia, 49032-490, Aracaju, SE, Brazil

IILaboratory of Infeccious and Parasitary Diseases, Science and Technology Institute. Aracaju, SE, Brazil

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE: This study analyzed the incidence of Entamoeba gingivalis and Trichomonas tenax in samples of dental biofilm and saliva from patients with gingivitis / periodontitis and in healthy subjects.

METHODS: Biofilm and saliva samples were taken from 20 patients with gingivitis, 22 with periodontitis and 9 healthy individuals. They were spread on sterile Petri dishes, diluted with saline and examined with a light microscope. Salivary pH was determined by universal pH indicators trips. The chi-square test was used to determine significance (p<0.05).

RESULTS: Almost one-third (31.37%) (50% from gingivitis and 50% from periodontitis) of the biofilm samples and 35.29% (39% from gingivitis and 61% from periodontitis) of the saliva samples were positive for Entamoeba gingivalis. Trichomonas tenax was found in 22.53% of the biofilm samples (16.66% from gingivitis, 41.67% from periodontitis and 41.67% from healthy patients) and 9.81% of the saliva samples (20% from gingivitis, 40% from periodontitis and 40% from healthy patients).The presence of these microorganisms was related to the type of periodontal disease (p=0.001), but not with age (p=0.178) or risk factors (p=0.194).

CONCLUSION: These findings suggest that Entamoeba gingivalis more common in the early stages of periodontitis, while Trichomonas tenax is considered a protozoan of the gingival sulcus. However, further studies are needed to determine the relationship between these species and periodontitis.

Indexing terms: Gingivitis. Parasitology. Periodontitis.

RESUMO

OBJETIVO: Analisar a incidência de Entamoeba gingivalis e Trichomonas tenax em amostras de biofilme dental e saliva de pacientes com gengivite/periodontite e de indivíduos saudáveis.

MÉTODOS: Amostras de saliva e biofilme foram obtidas de 20 pacientes com gengivite, 22 com periodontite e 9 indivíduos saudáveis. O material foi depositado em placas de Petri e diluído em soro fisiológico para posterior observação. O pH das amostras de saliva foi determinado com fitas indicadoras de pH. Os dados foram tratados por teste qui-quadrado (p<0,05).

RESULTADOS: Foi observada positividade para Entamoeba gingivalis em 31,37% das amostras de biofilme (50,00% com gengivite e 50,00% com periodontite) e 35,29% de saliva (39,00% gengivite e 61,00% periodontite). Foi observado o Trichomonas tenax em 22,53% das amostras de biofilme (16,66% gengivite, 41,67% periodontite, e 41,67% saudáveis) e 9,81% de saliva (20,00% gengivite, 40,00% periodontite, e 40,00% saudáveis). A presença de parasitas esteve relacionada ao tipo de doença periodontal (p=0,001), mas não a idade (p=0,178) e a fatores de risco (p=0,194).

CONCLUSÃO: Estes achados sugerem que a Entamoeba gingivalis aparece mais em estágios iniciais da periodontite, enquanto que o Trichomonas tenax é considerado um protozoário do sulco gengival. Contudo, outros estudos são necessários para determinar a relação entre essas espécies e a periodontite.

Termos de indexação: Gengivite. Parasitologia. Periodontite.

INTRODUCTION

The human oral cavity is home to numerous microorganisms1. Since mouth infection symptoms derive from the interaction between pathogenic microbiota and the host's defense mechanisms, it is extremely important to study the microorganisms that cause periodontal disease in adults. Hence, local irritating factors, particularly the dental bacterial biofilm, seem to have a critical role in the susceptibility to, and onset and progression of, periodontal disease2.

Microorganisms capable of colonizing the oral cavity are rare. Entamoeba gingivalis was the first commensal found in the human oral cavity, and it is found in gingival tissues, particularly in suppurative, inflammatory processes, due to its preference for anaerobic environments3. The high incidence of Entamoeba gingivalis in individuals with periodontal disease suggests that these protozoa might have an important role in the etiology of this condition4-5. However, since it is also found in the oral cavity of healthy individuals, some authors believe that this commensal could be opportunistic, that is, capable of proliferating in a gingival environment modified by periodontal disease3,6.

Trichomonas tenax, another protozoan which has been isolated from samples of dental calculi, is a member of the subgingival dental biofilm microbiota7. The presence of Trichomonas tenax in the human oral cavity is considered an indication of poor oral hygiene, since its incidence is about three or four times greater in patients with periodontal disease than in healthy individuals2,8-9.

The goal this study was to analyze the incidence of Entamoeba gingivalis and Trichomonas tenax in samples of dental calculi/biofilm and saliva from patients with periodontal disease and healthy patients and to determine if there is a relationship between periodontal disease and these protozoa.

METHODS

Patients

The periodontiums of 51 patients were clinically examined, and diagnosis and classification of the periodontium was done according to the Periodontal Screening and Recording (PSR) l, in agreement with the American Academy of Periodontology and American Dental Association criteria. Twenty patients were diagnosed with gingivitis (EG1), 22 with periodontitis (EG2) and 9 presented a healthy periodontium (CG). The patients were also asked about the use of medications and systemic conditions which might predispose them to the development of periodontal disease.

Sample collection

Samples of saliva and dental biofilm/calculi were collected from all patients in the morning, before any oral hygiene. After determining the frontal mandibular area most affected by periodontal disease (by means of PSR), dental biofilm/calculi samples were collected by scraping the area with sterile periodontal curettes. Unstimulated saliva samples were collected as recommended by Navazesh10. All samples were placed in sterile Petri dishes and diluted with saline at room temperature (25 to 28ºC). Immediately after dilution, the samples were examined under a light microscope.

Microbiological analysis of the samples

Sterile pipettes were used to put droplets of the samples on microscope slides, which were then examined under x100, x200 and x400 magnification. Strains of Entamoeba gingivalis were identified by their shape and presence of vacuoles containing inclusion bodies of the nuclear remains of lymphocytes, bacteria and erythrocytes.Trichomonas tenax was identified by its flagella and characteristic locomotion. Giemsa stain was used to facilitate Trichomonas tenax identification.

Determination of salivary pH

Universal indicator strips (pH 0-14, Merck®) were used to determine salivary pH and a possible relationship between pH and presence of the study microorganisms.

Statistical analyses

The data were analyzed by the non parametric chi-square test. The significance level was set at 5% (p<0.05).

Ethical and legal issues

This study followed the ethical principles in the Declaration of Helsinki (2000) and was approved by the local ethics committee, protocol number 131004.

RESULTS

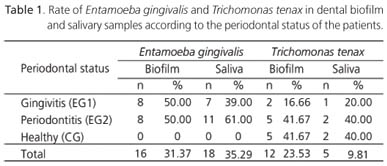

Analysis of the fresh microscope slides revealed that 16 biofilm samples (31.37%) were positive for Entamoeba gingivalis, where 50,00% (8 cases) were from patients with periodontitis and 50,00% were from patients with gingivitis. Entamoeba gingivalis was not found in the control group. Meanwhile, 12 (23.53%) biofilm samples were positive for Trichomonas tenax, where 41.67% (5 cases) were from patients with periodontitis, 16.66% (2 cases) were from patients with gingivitis and 41.67% (5 cases) were from the control group. As for the salivary samples, 18 (35.29%) were positive for Entamoeba gingivalis, where 61,00% (11 cases) were from patients with periodontitis and 39,00% (7 cases) were from patients with gingivitis. Once again, Entamoeba gingivalis was not found in the control group. Trichomonas tenax was identified in only 5 saliva samples (9.81%), where one (20,00%) was from a patient with gingivitis, 2 (40,00%) were from patients with periodontitis and 2 (40,00%) were from the control group (Table 1). There was a significant correlation between presence of microorganisms and type of periodontal disease (chi-square = 22.045, p=0.001).

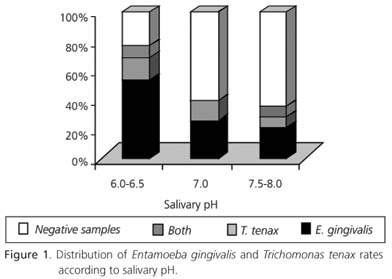

The salivary pH of the participants ranged from 6.0 and 8.0, and the likelihood of both microorganisms being present in the saliva decreased as salivary alkalinity increased (Figure 1).

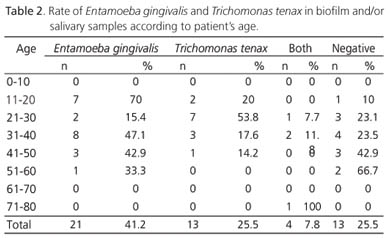

Regarding the relationship between patient's age and presence of microorganisms, Entamoeba gingivalis was more common in individuals aged 31 to 50 years, whereas Trichomonas tenax was more common in patients aged 11 to 30 years (Table 2). However, both commensals were found in a wide range of ages, so no statistically significant correlation was found between age and presence of microorganisms (chi-square = 8.915; p=0.178).

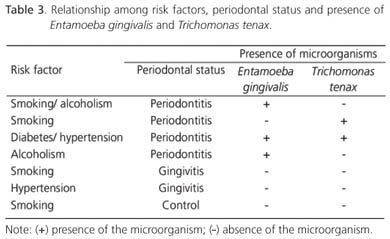

Only 8 (15.6%) of the 51 individuals examined in this study presented risk factors for periodontal disease, such as alcoholism (2 cases), smoking (5 cases), hypertension (2 cases) and diabetes (1 case) (Table 3). There was no correlation between the incidence of protozoa and these risk factors (chi-square = 9.652; p=0.194)

DISCUSSION

Most studies on oral microorganisms refer to bacteria, and there are only a few reports on the role of oral commensals in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease despite the high incidence of certain protozoa, such as Trichomonas tenax and Entamoeba gingivalis, in the dental biofilm11. Epidemiological studies have showed that the infection rate of Entamoeba gingivalis in patients with periodontitis is much higher than that of healthy patients12, so some researchers inferred that this protozoan was related to periodontitis13. In addition, there are some reports indicating that the prevalence of people with Trichomonas tenax world wide ranges from 4.0 to 53%; besides, some studies have reported a high prevalence of this commensal in patients with chronic marginal periodontitis5,11.

Protozoa were found in 74.5% of the patients, and Entamoeba gingivalis was almost twice as common as Trichomonas tenax. Very similar results were found by other studies2,14-15. Additionally, in 10% of the cases (all with periodontitis), both microorganisms were present, corroborating other studies16-18.

Entamoeba gingivalis, found only in the dental biofilm and saliva of patients with periodontal disease, corroborates the hypothesis that this protozoan might be involved in the development of periodontal disease, as has been suggested by other studies3,11,14.

It has been suggested that Entamoeba gingivalis could affect the formation of the dental biofilm and contribute to the development and progression of periodontal disease1. On the other hand, other researchers state that this microorganism may be opportunistic, since it is capable of proliferating in the microenvironment of the mucobuccal fold affected by periodontal disease6. Moreover, some aerobic (Pseudomonas aeruginosa) and facultative anaerobic bacteria (Klebsiella pneumonia) may cause periodontitis in rats when are given immunosuppressive drugs and Entamoeba gingivalis can help the bacteria to cause periodontal disease3.

Therefore, if Entamoeba gingivalis helps the development and progression of periodontal disease and periodontal disease increasingly facilitates the proliferation of these protozoa, this vicious circle could explain the increased incidence of these microorganisms in the dental biofilm of patients with gingivitis and periodontitis4.

Some authors injected Entamoeba gingivalis in the base of the gingival pocket of rats, which induced periodontal abscess in 78.9% (30/38) of sample. Live Entamoeba gingivalis were found in purulent secretions and cultured from the periodontal abscess. These results strongly suggest that infection by Entamoeba gingivalis may destroy the gingival tissues. Furthermore, it has also been proposed that salivary enzymes and free radicals in patients with Entamoeba gingivalis-induced periodontitis may be involved in the lysing of the plasmalemma and membranous organelles, damaging the epithelial cells of the gums19.

A suspension of Entamoeba gingivalis was spread on the gingival margins of rats immunosuppressed with prednisolone, leading to the development of the clinical signs of periodontal disease much faster than that observed in immunocompetent rats4. These data indicate that immunosuppression may play a role in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease induced by this commensal.

The prevalence of Trichomonas tenax in the present study (23.53%) was in agreement with many other studies that reported prevalences ranging from 12 to 32%1,11,20-21.

The role of Trichomonas tenax in periodontal disease is still controversial. Although a relationship between the increased occurrence of this protozoan and progression of periodontal disease has been demonstrated recently5,7, the precise mechanism of tissue damage is still unknown.

It has been demonstrated that Trichomonas tenax presents proteolytic activity mediated by cysteine endopeptidases which hydrolyze different types of collagen molecules (types I, III, IV and V) present in all periodontal tissues22-23. Additionally, this protozoan can also lyse human eritrocytes24. Acid phosphatase has also been found in vesicles structures of Trichomonas tenax in the Golgi apparatus, in primary and secondary lysosomes, in cytoplasmic granules and in the free extremity of the waving membrane25. Therefore, these studies seem to suggest a more active role of Trichomonas tenax in the progression of periodontal disease. However, further studies are necessary for the complete elucidation of this issue.

Not with standing the above mentioned data, the high proportion of healthy individuals with Trichomonas tenax in contrast with the low proportion of patients with gingivitis and Trichomonas tenax found by the present study suggests that gingival inflammation may modify the microenvironment of the gingival pockets and disrupt the colonies of this microorganism. On the other hand, the high proportion of patients with periodontitis (inflammation of the periodontium with progressive bone loss) and Trichomonas tenax instigates other speculations, such as that the progression of periodontal disease could some how promote other significant changes in the dental biofilm making it susceptible to new Trichomonas tenax colonies.

Salivary pH ranged from 6.0 to 8.0, but the peak incidence of commensals in salivary samples occurred between pH 6.0 and 6.5. As the pH increased becoming more alkaline, the incidence of the study microorganisms decreased, suggesting that a more acidic pH provides a better environment for these microorganisms. These findings are corroborated by other studies17,26. However, still other studies have not found a relationship between salivary pH and the presence of these protozoa18.

Regarding gender, both parasites were more common in females, but the difference was not statistically significant. These data are in agreement with those of other studies27-28.

Age is also considered a predisposing factor for protozoan infection in patients with periodontal disease. Several authors reported that the incidence of Entamoeba gingivalis and Trichomonas tenax increases with age9,16,29. However, no statistically significant correlation between age and presence of oral commensals was observed in this study. This apparent contradiction may be related to an absence of age group standardization.

Other factors that increase the risk of periodontal disease are diabetes, infection with anaerobic Gram-negative species and smoking30.

Tobacco is capable of reducing the synthesis of IgG and IgM by plasma cells, as well as the phagocytic activity and chemotactic response of gingival neutrophils, so the host's defense against bacteria in the gingival pocket is substantially impaired21.

There are contradicting reports in the literature regarding diabetes: one study reports a high incidence of these commensals (74%) in adult diabetics2 and another study reports a low incidence28.

CONCLUSION

The present study did not find a relationship between the presence of Entamoeba gingivalis and Trichomonas tenax and smoking, alcoholism and diabetes. In fact, risk factors for periodontal disease were present in only a few participants, so any inference or deliberation on this subject should be cautious.

The results of this research suggest that Entamoeba gingivalis occurs more frequently in the early stages of periodontal disease, whereas Trichomonas tenax sees the oral cavity as its natural habitat given its commonness in individuals with healthy gums. However, further studies are necessary for determining the real nature of the relationship between these species and periodontal disease

Collaborators

RLC ALBUQUERQUE JÚNIOR assessed the teeth and gums. CM MELO performed the microbiological analyses. WA SANTANA wrote and reviewed the article. JL RIBEIRO and FA SILVA performed the study.

REFERENCES

1. Feki A, Molet B. Importance of Trichomonas tenax and Entamoeba gingivalis protozoa in the human oral cavity. Rev Odontostomatol. 1990;19(1):37-45. [ Links ]

2. Nocito Mendoza I, Vasconi Correas MD, Ponce de Leon Horianski P. Entamoeba gingivalis and Trichomonas tenax in diabetic patients. RCOE. 2003;8(1):13-23. [ Links ]

3. Chen JF, Wen WR, Liu GY, Chen WL, Lin LG, Hong HY. Studies on periodontal disease caused by Entamoeba gingivalis and its pathogenetic mechanism. Rev China Med J. 2001;114(12):12-5. [ Links ]

4. Al-Saeed WM. Pathogenic effect of Entamoeba gingivalis on gingival tissues of rats. Al-Rafidain Dent J. 2003;3(1):70-3. [ Links ]

5. Athari A, Soghandi L, Haghighi A, Kazemi B. Prevalence of oral trichomoniasis in patients with periodontitis and gingivitis using pcr and direct smear. Iranian J Publ Health. 2007;36(3):33-7. [ Links ]

6. El-Azzoumi M, El-Brady AMS. Frequency of Entamoeba gingivalis among periodontal and patients under chemotherapy. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 1994;24(3):649-55. [ Links ]

7. Kurnatowska AJ, Dudko A, Kurnatowski P. Invasion of Trichomonas tenax in patients with periodontal diseases. Rev Wiad Parazytol. 2004;50(3):397-403. [ Links ]

8. Pardi G. Trichomonas tenax: protozoario flagelado de la cavidad bucal. Consideraciones generales. Acta Odontol Venez. 2002;40(1):47-55. [ Links ]

9. Pardi G, Perrone M, Ilja RM. Incidencia de Trichomonas tenax en pacientes com periodontitis marginal crónica. Acta Odontol Venez. 2002;40(2):152-9. [ Links ]

10. Navazesh M. Methods for collecting saliva. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;694:72-7. [ Links ]

11. Sarowska J, Wojnicz D, Kaczkowski H, Jankowski S. The occurrence of Entamoeba gingivalis and Trichomonas tenax in patients with periodontal disease. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2004;13(2):291-7. [ Links ]

12. Al-Saeed WM, Mahmood HJ. Prevalence of Entamoeba gingivalis in dental patients in Mosul. Al-Rafidain Dent J. 2001;1(1):65-8. [ Links ]

13. Chen JF, Liu GY, Wen WR. Studies on the continuous culture and pathogenicity of Entamoeba gingivalis. Chin J Parasitol Parasitic Dis. 2000;18(2):84-6. [ Links ]

14. Feki A, Molet B, Haag R, Kremer M. Protozoa of the human oral cavity (epidemiological correlations and pathogenic possibilities). J Biol Buccale. 1981;9(2):155-61. [ Links ]

15. Corrêa DP, Giazzi JF, Martinez I. Proposta de uma nova técnica de detecção de Entamoeba gingivalis e Trichomonas tenax. Rev Ciênc Farm. 1998;19(2):245-9. [ Links ]

16. Vrablic J, Tomova S, Catar G, Randova L, Suttova S. Morphology and diagnosis of Entamoeba gingivalis and Trichomonas tenax and their occurrence in children and adolescents. Bratisl Lek List. 1991;92(5):241-6. [ Links ]

17. Zdero M, Ponce de Leon P, Vasconi MD, Nocito-Mendonza I, Lucca A. Entamoeba gingivalis y Trichomonas tenax: hallazgo en poblaciones humanas con y sin patología bucal. Acta Bioquím Clín Lat-Amer. 1999;30:359-65. [ Links ]

18. Ponce de León P, Zdero M, Vasconi M.D, Nocito-Mendonza I, Lucca A, Perez, B. Relation between buccal protozoa and pH and salivary IgA in patients with dental prothesis. Rev Inst Med Trop S Paulo. 2001;43(4):241-2. [ Links ]

19. Liu GY, Chen JF, Wen WR. The content and roles of enzymes and MDA in saliva of patients with periodontitis induced by Entamoeba gingivalis. J Clin Stomatol. 2000;16(1):10-2. [ Links ]

20. Vrablic J, Tomova S, Catar G. Occurrence of the protozoa, Entamoeba gingivalis and Trichomonas tenax in the mouths of children and adolescents with hyperplastic gingivitis caused by phenytoin. Bratisl Lek Listy. 1992;93(3):136-40. [ Links ]

21. Hayawan IA, Bayoumy MM. The prevalence of Entamoeba gingivalis and Trichomonas tenax in periodontal disease. J Egypt Soc Parasito. 1992;22(1):101-5. [ Links ]

22. Bozner P, Demes P. Degradation of collagen types I, III, IV and V by extracellular proteinases of an oral flagellate Trichomonas tenax. Archs Oral Biol. 1991;36(10):765-70. [ Links ]

23. Segovic S, Buntak-Kobler D, Gallc N, Katunaric M. Trichomonas tenax proteolytic activity. Coll Antropol. 1998;22(Suppl):45-9. [ Links ]

24. Nagao E, Yamamoto A, Igarashi T, Goto N, Sasa R. Two distinct hemolysins in Trichomonas tenax ATCC 30207. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2000;15(6):355-9. [ Links ]

25. Ribaux CL, Magloire H, Joffre A. Donnés compleméntaires à l´étude ultrastructurale de Trichomonas tenax. Localization intracellulaire de la Phosphatase Acide. J Biol Buccale. 1980;8:213-28. [ Links ]

26. Souza EM. Estudo de Entamoeba gingivalis em boca de crianças. Rev Microbiol. 1982;13(2):173-9. [ Links ]

27. Arene FO. Entamoeba gingivalis: prevalence amongst in habitants of the Niger Delta. Tropenm und Parasitol. 1984;35(4):251-2. [ Links ]

28. Linke HA, Gannon JT, Obin JN. Clinical survey of Entamoeba gingivalis by multiple sampling in patients with advanced periodontal disease. Int J Paraditol. 1989;19(7):803-8. [ Links ]

29. Ragghianti MS, Greghi SLA, Lauris JRP, Sant'Ana ACP, Passanezi E. Influence of age, sex, plaque and smoking on periodontal conditions in a population from Bauru. Brazil. J Appl Oral Sci. 2004;12(4):273-9. [ Links ]

30. Pomes CE, Bretz WA, Leon A, Aguirre R, Milian E, Chaves ES: Indicadores de risco para as doenças periodontais em adolescentes guatemaltecos. Braz Dent J. 2000;11(1):49-57. [ Links ]

Received on: 9/7/2010

Approved on: 3/11/2010

* Correspondence to: RLC ALBUQUERQUE JÚNIOR. E-mail: <ricardo.patologia@uol.com.br>.