Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

RGO.Revista Gaúcha de Odontologia (Online)

versão On-line ISSN 1981-8637

RGO, Rev. gaúch. odontol. (Online) vol.63 no.2 Porto Alegre Abr./Jun. 2015

ORIGINAL / ORIGINAL

Mothers' perceptions about pediatric dental sedation as an alternative to dental general anesthesia

Percepção de mães sobre sedação em odontopediatria como uma alternativa à anestesia geral

Alessandra Rodrigues de Almeida LIMAI; Marcelo MEDEIROSII; Luciane Rezende COSTAII

I Secretaria de Estado da Saúde de Goiás, Gerência de Ouvidoria. Rua SC-1, 299, Parque Santa Cruz, 74860-270, Goiânia, GO, Brasil

II Universidade Federal de Goiás, Faculdade de Odontologia. Goiânia, GO, Brasil

ABSTRACT

Objective

Moderate sedation has limits in managing children's behavior. Existing literature lacks insight into parental perceptions about the topic. This study aimed to understand mothers' perceptions concerning sedation after their children undergone dental treatment under sedation.

Methods

Twelve mothers and one godmother of 1.3-8.4 year-old children with definitely negative behavior in the dental chair, who had dental treatment under oral sedation, were in depth interviewed according to a semi-structured guide. Responses were analysed using a thematic content method and deductive approach. Two general themes were addressed: "good facet" and "poor facet" of pediatric dental sedation.

Results

Analysis of interview transcripts indicated that participants perceived pediatric dental sedation according to two main analytical categories: the "good facet" and the "poor facet". The good facet included advantages of the procedure (e.g. safety, effective behavior management), rapport and completion of the treatment that was initially planned. The poor facet related to limitations of moderate sedation (when child kept struggling) and their own anxiety during the procedure.

Conclusion

Despite their own stress, mothers were satisfied with this pharmacological method of behavior management.

Indexing terms: Conscious sedation. Parents. Pediatric dentistry. Perception. Qualitative research.

RESUMO

Objetivo

Sedação moderada tem limites no gerenciamento do comportamento infantil. A literatura existente carece de estudos sobre as percepções dos pais a cerca do tema. Este estudo objetivou compreender a percepção das mães sobre sedação após o tratamento dentário de suas crianças sob sedação.

Métodos

Doze mães e uma madrinha de crianças de 1.3–8.4 anos, com comportamento definitivamente negativo na cadeira odontológica, que tiveram tratamento odontológico sob sedação oral, foram entrevistadas em profundidade segundo um roteiro semi-estruturado. As respostas foram analisadas usando o método de análise de conteúdo temático e abordagem dedutiva. Foram abordados dois temas gerais: "lado bom" e "lado ruim" da sedação odontopediátrica.

Resultados

Análise das entrevistas transcritas indicou que as participantes percebem a sedação odontopediátrica de acordo com duas categorias: "o lado bom" e a "o lado ruim". O lado bom incluiu vantagens do procedimento (por exemplo, segurança, gerenciamento eficaz do comportamento), suporte e conclusão do tratamento odontológico inicialmente planejado. O lado ruim foi relacionado às limitações da sedação moderada (quando a criança continuou lutando) e sua própria ansiedade durante o procedimento.

Conclusão

Apesar de seu próprio estresse, as mães estavam satisfeitas com este método farmacológico de gestão de comportamento.

Termos de indexação: Sedação consciente. Pais. Odontopediatria. Percepção. Pesquisa qualitativa.

INTRODUCTION

Dental fear and anxiety (DFA) as well as dental behavior management problems (DBMP) each affect up to 9% of children and adolescents1. Particularly in pediatric dentistry, initial attempts to manage children's behavior involve basic techniques2-3, such as communicative guidance, tell-show-do, voice control, nonverbal communication, positive reinforcement, distraction, parental presence/absence and administration of nitrous oxide/oxygen. When those fail, advanced behavior guidance can be employed3-5, typically involving protective stabilization (i.e. physical restraint), sedation and general anesthesia. Among the variety of behavioral management techniques available, the most controversial are protective stabilization, sedation and general anesthesia, which should be recommended for the benefit of the child, considering the norms and values of a particular community2.

Moderate (conscious) sedation for outpatient procedures can be controversial in pediatric dentistry because its efficacy, effectiveness and safety depend on several factors. A successful sedation is based on a minimum of the child's ability to tolerate dental treatment and cooperate with the dentist. Negative stimuli associated with dental procedures, such as light, air, water, local anesthesia, noise and trepidation, can still cause discomfort in children under moderate sedation6, resulting in potential failure of the procedure due to crying, struggling, or generally poor behavior. As such, the combined use of protective stabilization and moderate sedation may be an alternative to general anesthesia7. No sedative is available to completely suppress anxiety and/or behavior problems of children in the dental chair. Although oral midazolam has been shown to marginally improve a child's tolerance for dental treatment, further studies are needed to evaluate other sedation agents8. Parents should be informed in advance of the possibility of sedation failure.

Few reports about parents' perceptions about pharmacological behavior management techniques are available. A study reported that 93% of parents of children treated under general anesthesia said that it was an easy experience and all of them were satisfied9. According to another investigation, low-income mothers of children referred for dental treatment under sedation had never heard about many concepts related to that pharmacological procedure until then10. Those mothers, after being informed about the sedation risks and limitations, decided to consent with their child dental sedation because their children were suffering with dental caries and had gone through several attempts of dental treatment (using no sedative) without success10.

The understanding of families' perspectives about pediatric dental sedation is relevant for the development of clinical guidelines, considering that in the absence of satisfactory conditions for general anesthesia, sedation may be indicated to manage the child's behavior for dental treatment. Yet, the aforementioned investigation10 did not seek parents' perceptions about dental sedation after procedures were performed. The current study sought to evaluate mothers' perceptions about sedation after the conclusion of their children's dental treatment under such conditions.

METHODS

Study design

The current study adopted a qualitative approach, which is used to investigate opinions, attitudes, values, and beliefs11. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the Federal University of Goias (Goiania, Goias, Brazil), by Protocol 003/2003, and followed international and national ethics regulations for studies involving human subjects, including the Helsinki Declaration. Participants signed the consent form after had received verbal and written information about the aims and procedures of the study, and were informed that participation was voluntary.

Participants

The target population was the accompanying adult of children treated under dental sedation at the Dental Sedation Center (NESO) of the Federal University of Goias Dental School, Brazil. NESO is an extension project performed on an outpatient basis and focused on providing dental treatment for children of low-income households referred by the community public service because of their negative behavior during a dental consultation.

The study included one adult per child. Participants were required to be the adult responsible for caring for the child during and after dental treatment. The number of subjects included in the study was based on the saturation principle, where the researcher's intention is to keep sampling and analyzing data until nothing new is being generated and no new topics emerge because the respondents' answers are similar12. None individuals refused to participate in the study, and no one had to be interviewed again.

In total, 12 mothers and 1 godmother participated in this qualitative research study. Their ages ranged from 19 to 38 years old. All of them were Brazilian and had formal education. Specifically, half had completed or almost completed secondary school. Results were presented by quoting "mothers", which was the term used to refer to all study participants, including the godmother. In the results section, the perception of godmother was highlighted if it was different from mothers.

Sedation procedures

Eight boys and 5 girls aged 1.3 to 8.4 years old required extensive dental treatment under sedation. Behavior for all children was classified as "score 1" according to the Frankl Behavior Rating Scale13, indicating definite negative behavior, such as blatantly refusing treatment, crying forcefully, showing fearfulness, being combative, and other behavior conveying overt negativism. In total, 55 procedures under moderate sedation were attempted, but planned treatment was only accomplished in 58% of cases, when children exhibited satisfactory behavior (scores of 4 to 6) according to the Houpt scale14. For the purpose of this study, moderate sedation was defined as a drug-induced depression of consciousness to reduce anxiety, thus allowing treatment to be carried out satisfactorily while patients were still able to respond to verbal commands, as well as maintain protective reflexes and a patent airway.

NESO's protocol adheres to American and European guidelines4-5,15. There is a first consultation with the physician to determine a child's health status and with the dentist to determine that a child meets the criteria for a safe dental sedation. As dental treatment under general anesthesia is restricted in Brazilian public service due to deficiency of proper surgical center, many children are indicated for sedation in NESO due to lack of choice of general anesthesia. NESO protocol includes shared decision-making between the multidisciplinary team and child's parents or guardians. On the day of the procedure, a team member administers an oral sedative, and the patient is monitored during sedation until discharge. At the time of discharge, post-operative recommendations are made. A physician (pediatrician or anesthesiologist) is present throughout the entire treatment. For the current study, drug protocol was restricted to oral midazolam (0.75-1.0 mg/kg to a maximum of 20 mg) or oral chloral hydrate (70-100 mg/ kg to a maximum of 2 g) without nitrous oxide/oxygen supplementation.

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were individually conducted with each mother. In a semi-structured interview, there is a guide with open questions established by the research, but interviewees' can bring up new ideas related to the study aim12. The topics in the interview guide included mothers' satisfaction and feelings/perceptions during the dental sedation. The interview guide adequacy was tested in a pilot study with 3 participants, who had their responses included in the final analysis: as small adjusts were made, it was possible to got back to the interviewees to know their additional information, which is one advantage of qualitative studies.

All of the interviews were conducted face-toface by the first author, who is a female pediatric dentist with Master's degree and previous training for conducting interviews. Interviews occurred after completion of the dental procedure under sedation, and were scheduled at the participants' convenience when they returned to the clinic for follow-up consultation. Interviews were conducted in a designated room, including only the interviewer, the mother and, occasionally, the child.

Data analysis

Interviews were recorded using a tape recorder; responses were transcribed verbatim by the interviewer, allowing data interpretation through content analysis16. Transcripts received minor grammatical corrections to improve clarity.

Qualitative content analysis is a research method used for subjective interpretation of text data through the systematic classification process of coding and identifying themes or patterns. In conventional content analysis, coding categories are derived directly from the text data. This type of design is appropriate when research literature on a phenomenon is limited17.

Thematic content analysis was chosen to analyze the responses because it is the most common type of qualitative analysis seen in health journals and aims to report the key element of respondents' accounts. When performing a thematic content analysis, interview transcripts are used to categorize respondents' accounts in ways that can be summarized, allowing researchers to compare and to discuss the meaning of their data12.

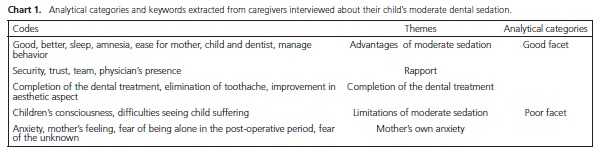

In this study, original codes were assigned to mark themes identified in the transcripts that were relevant to the area of inquiry. Related codes were then grouped together as themes; these were subsequently linked in analytical categories (Chart 1). We established two aprioristic categories: positive and negative aspects of pediatric dental sedation.

To ensure reliability and validity of findings, all study authors individually reviewed the whole data set, performed an analysis of discordant cases to confirm data, and compared data between and within cases in the data set. Other features of a rigorous qualitative analysis include transparency (by providing a clear account of procedures used), an "audit trail" that readerscan follow (including enough context to judge interpretation) and comparison of findings to other studies12.

RESULTS

Analysis of interview transcripts indicated that participants perceived pediatric dental sedation according to two main analytical categories (Chart 1): the "good facet" and the "poor facet".

Sedation's good facet

The "good facet" category included all positive feelings about the procedure, such as safety, rapport, completion of dental treatment, and effective behavior management (Chart 1).

In this study, mothers were informed of the risks and limitations of the oral sedation procedure during the informed consent process:

"Because they gave me the informed consent form to read, I know that there is risk." E1

"No, not really (not worry about child did not sleep), because in fact I knew that she might sleep or not." E3

Mothers viewed protective stabilization as a good strategy to increase the child's security, probably because they built a rapport with staff. Also, mothers found that the presence of a physician and his own presence during the procedure was positive:

"I even noticed the way you held her, because I was there […] I was always paying attention and you did not hurt her. And this did not trouble me because you were helping me."E5

"And here the doctor was always on the side." E10

Despite the limitations of moderate sedation, several mothers expressed their satisfaction:

"This session was better; in the last session it was worse, she did not stop struggling."E3

"I think although he cried, and needed to be held, there were so many advantages comparing to the treatment without sedation."E10

Based on the responses, satisfaction appeared to be strongly associated with completion of dental treatment, which meant relief from pain and/or aesthetic improvement:

"They filled it, didn't they? Every little tooth. They stopped her pain [...] Her teeth got beautiful. Mainly here at the front, her smile was ugly."E3

Despite difficulties, mothers considered sedation to be necessary for their children's well being. Furthermore, they indicated that they would choose sedation again if non-pharmacological behavior management techniques were unsuccessful. Specifically, crying was more intense and physical resistance was stronger without medication. Mothers believed that their children might not require pharmacological behavior management techniques in the future since the children may now be more receptive to brushing their teeth.

Sedation's poor facet

The "poor facet" category included negative aspects mentioned during the interviews, such as fear of the unknown and difficulty having to watch their children's discomfort (Chart 1). In particular, some mothers described significant difficulty and suffering for having to witness their child crying because of their "mother's heart" and "mother's feeling":

"[...] seeing him crying, sometimes looking at me ... I wanted to cry too."E1

"A mother, you know, is always afraid of everything. The moment someone is dealing with her son, they are dealing with her, so I felt insecure, scared, and I'd rather try another method."E5

Although mothers were advised that their child could sleep at home after sedation, most expressed concern and felt insecure being alone without the dentist, physician, and monitoring equipment:

"But, I felt more secure here than alone. When I'm alone, I think I'm nobody."E5

Speaking with the dentist by telephone after the dental sedation session did not minimize that postoperatory anxiety in one case; that mother withdrew her consent after the initial sedation session, and chose to try non-pharmacological behavior management techniques.

With no additional instructions on how to potentially help their children cope, some mothers had a tendency to make comments that were counterproductive to behavior management based on feelings of powerlessness:

"These people in white hurt you, my darling?" E7 (While saying this, the mother breastfed her 3 years old child to help him sleep after completing a dental session).

Interestingly, the aforementioned overprotection occurred with many of the participants, while the only godmother to participate specifically focused on the good side of the dental session and praised the treatment team.

Overall, mothers experienced initial anxiety related to fear of the unknown and fear of anesthesia. Despite the information given during the consent process, mothers related anxiety on the eve before the first sedation session:

"In the first day I was feeling more nervous than the others." E7

DISCUSSION

Despite difficulties having to witness crying and discomfort of their child, mothers showed satisfaction with moderate dental sedation. This satisfaction was primarily related to the completion of dental treatment. According to the literature, roughly 95% of all patients that undergo dental deep sedation or general anesthesia are satisfied with the procedure9,18, but no such quantitative data is available for moderate pediatric dental sedation. One study reported that the moderate sedation dissatisfaction predictors for parents were younger patients, anxiety, pain, and sickness; however, satisfaction predictors were not investigated18. Another study10 investigating mothers' expectations before their children had undergone dental moderate sedation anticipated the findings of the present study, because what mothers expected the most was the completion of the dental treatment, even if the sedation was not effective. This study's population had a dental history of not accomplished treatments, so the mothers' concerns were more related to the dental treatment itself as well.

In the current study, mothers were able to identify good and poor facets of moderate dental sedation. Detailed explanation (informed consent), presence of a physician, and protective stabilization were considered positive aspects of dental sedation - a way to achieve dental treatment conclusion - and teamwork was praised. Conversely, mothers found it difficult to witness the suffering of their child, often wishing to trade places with their child to alleviate the suffering. Interestingly, the only godmother included in the study did not express such feelings. Furthermore, fear of the unknown before the first dental sedation session and after the child was discharged led some mothers to feel helpless.

Informed consent is an essential step in pediatric pharmacological behavior management3-4, but occasionally the legal guardian does not completely understand the procedure19. The NESO protocol for informed consent recognizes that the best way to convey the information is oral explanation by the dentist20 followed by written consent by the parents/patients3-4. Agreement to proceed with a particular behavior management method is influenced by the way it is presented to the parent21. The current study showed that clear explanation of the risks, complications, and limits of moderate sedation did not cause additional or excessive worry. Once mothers learned about possible behavior alterations and complications, they generally became more comfortable asking the dental team questions about the sedation procedure. Moreover, having become familiarized with the monitoring procedures, mothers could observe the team carefully.

Mothers from this study thought that the presence of a physician provided additional comfort and security for their children during moderate dental sedation. According to the Brazilian legislation (Law 5081/1966, article 6th): "It is the responsibility of the dentist (…) VI. to employ analgesia and hypnosis since proven enabled when they constitute effective means for dental treatment"22.So, the presence of a physician is not mandatory during moderate dental sedation as long as the dentist has proper training to perform dental sedation.

If it is necessary to treat and protect the safety of a child, practitioner, and parents, protective stabilization should be considered3, and it should never be forcefully administered or used as punishment4,23. Moderate sedation associated with protective stabilization is an alternative to general anesthesia7. Protective stabilization is necessary during pediatric dental sedation in 50-94% of cases24-25. Unexpectedly, protective stabilization of a fully conscious child did not cause any distress for the caregiver in the present study. Instead, mothers praised the dedication and loving attitude of the team. Such findings demonstrate the necessity to humanize dental practice even when sedation is performed and aversive methods such as protective stabilization have to be used.

Crying and movement are expected during moderate dental sedation, because patients keep the ability to respond to unwanted oral/tactile stimulus15. Although the caregiver was informed that crying and movement could occur, mothers, but not the godmother, had difficulties accepting their child's resistance in the dental chair, often feeling powerless and guilty, which was particularly evident when mothers' eyes watered. According to participants, this feeling was due to their "mother's heart". Although aware of the necessity of the dental treatment, mothers wanted to cry with their child and trade places in hopes of alleviating the discomfort of their child, which is consistent with findings from another study26. The godmother did not share similar feelings. Instead, she just felt physically tired because she had to help with the stabilization.

One major limitation of this study is that qualitative research does not aim to acquire data that can be generalized from the study cohort to a larger population. Rather, the purpose of the research is to capture a range of views and experiences11-12, by investigating how a group will cover the problem studied27. In fact, qualitative methodology studies phenomena within a context from the interpretation of people who experience them, allows the in-depth understanding of health behaviors, has a flexible design, favors the integration between social and health sciences, but requires greater time on data analysis when compared with quantitative research11-12,27-28.

Our results cannot be extrapolated because perceptions as well as social representations depend on the life experience of individuals from the target group. Instead, the concept of transferability can be applied, that is, the present findings have applicability in other similar contexts28. Participants of this study included mothers of children requiring extensive dental treatment, but exhibiting extremely negative behavior towards the procedures, which represent a questionable indication for moderate sedation. Maybe general anesthesia could be better prescribed in those cases, but families could not pay for it. Thus, the vulnerability of the child's family may also contribute to the overall satisfaction observed in this study, which constitutes another limitation of the present results.

Regardless, this study highlights the importance of good communication in dentistry to establish a rapport with the patient and family. Further investigation is needed to determine the quantitative aspects of parents' satisfaction with moderate dental sedation as this procedure has been more frequently used.

CONCLUSION

Mothers were satisfied with the completion of children's dental treatment under moderate sedation, even if sedation was not successful in managing child's behavior; their satisfaction was related to the instructive process of informed consent, presence of a specialized physician, and humanized care during protective stabilization. Mothers also realized some negative aspects in moderate sedation for their children, such as their own guilt for having to watch the persistent struggling of their child in the dental chair and fear of being alone with the child at home after discharge.

Collaborators

ARA LIMA was responsible for preparing the design, data collection, data analysis, preparation of article and writing the article. M Medeiros and LR COSTA were responsible for Project design, data analysis and writing the article.

REFERENCES

1. Klingberg G, Broberg AG. Dental fear/anxiety and dental behavior management problems in children and adolescents: a review of prevalence and concomitant psychological factors. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2007;17(6):391-406. doi: 10.1111/j.1365- 263X.2007.00872.x [ Links ]

2. Roberts JF, Curzon ME, Koch G, Martens LC. Review: behavior management techniques in pediatric dentistry. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2010;11:16-74.

3. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD). Guideline on behavior guidance for the pediatric dental patient. Pediatr Dent. 2011-2012; 33:161-73.

4. Hallonsten AL, Jensen B, Raadal M, Veerkamp J, Hosey MT, Poulsen S. EAPD Guidelines on Sedation in Pediatric Dentistry. In: European Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. 2005. [cited in 2013 Feb 13] Avalable from: <http://www.eapd.gr/dat/5CF03741/file.pdf>.

5. Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme (SDCEP). Conscious sedation in Dentistry: Dental clinical guidance. Dundee: University of Dundee; 2012.

6. Colares V, Richman L. Factors associated with uncooperative behavior by Brazilian preschool children in the dental office. ASDC J Dent Child. 2002;69(1):87-91.

7. Kupietzky A. Strap him down or knock him out: is conscious sedation with restraint an alternative to general anesthesia? Br Dent J. 2004;196(3):133-8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4810932

8. Matharu LL, Ashley PF, Furness S. Sedation of children undergoing dental treatment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;3:CD003877. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003877

9. Savanheimo N, Vehkalahti MM, Pihakari A, Numminen M. Reasons for and parental satisfaction with children's dental care under general anesthesia. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2005;15(6):448- 54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2005.00681.x

10. Lima ARA, Costa LRRS, Medeiros M. Dealing with myths: the need for community education on anesthetic practices in dentistry. Arq Odontol. 2005;41:51-63.

11. Flick U. An introduction to qualitative research. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2009.

12. Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research. London: Sage; 2010.

13. Frankl SN, Shiere FR, Fogels HR. Should the parent remain with the child in the operatory? ASDC J Dent Child. 1962;2:150-63.

14. Houpt MI, Koenigsberg SR, Weiss NJ, Desjardins PJ. Comparison of chloral hydrate with and without promethazine in the sedation of young children. Pediatr Dent. 1985; 7(1):41-6.

15. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD). Guideline for monitoring and management of pediatric patients during and after sedation for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Pediatr Dent. 2011-2012; 33:185-201.

16. Bogdan RC, Biklen SK. Qualitative research for education. Boston: Prentice Hall; 2002.

17. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277-88.

18. Coyle TT, Helfrick JF, Gonzalez ML, Andresen RV, Perrott DH. Office-based ambulatory anesthesia: factors that influence patient satisfaction or dissatisfaction with deep sedation/general anesthesia. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63(2):163-72. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2004.10.003

19. Mohamed MAT, Mason C, Hind V. Informed consent: optimism versus reality. Br Dent J. 2002;193(4):181-4.

20. Armfield JM, Spencer AJ, Stewart JF. Dental fear in Australia: who's afraid of the dentist? Aust Dent J. 2006;51(1):78-85. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2006.tb00405.x

21. Kupietzky A, Ram D. Effects of a positive verbal presentation on parental acceptance of passive medical stabilization for the dental treatment of young children. Pediatr Dent. 2005;27(5):380-4.

22. Brasil. Presidência da República, Casa Civil. Lei n. 5081, de 24 de agosto de 1966. Regula o Exercício da Odontologia [online]. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília (DF); 1966 ago 24 [citado 2014 Out 10]. Disponível em: < http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/ leis/l5081.htm>.

23. Allen KD, Hodges ED, Knudsen SK. Comparing four methods to inform parents about child behavior management: how to inform for consent. Pediatr Dent. 1995;17(3):180-6.

24. Crock C, Olsson C, Phillips R, Chalkiadis G, Sawyer S, Ashley D, et al. General anesthesia or conscious sedation for painful procedures in childhood cancer: the family's perspective. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88(3):253-7.

25. Lima ARA, Costa LRRS, Costa PSS. A randomized, controlled, crossover trial of oral midazolam and hydroxyzine for pediatric dental sedation. Braz Oral Res. 2003;17(3):206-11. doi: 10.1590/S1517-74912003000300002

26. Oliveira VJ, Costa LRRS, Marcelo VC, Lima ARA. Mothers' perceptions of children's refusal to undergo dental treatment: an exploratory qualitative study. Eur J Oral Sci. 2006;114(6):471- 7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2006.00405.x

27. Minayo MCS, Sanches O. Qualitativo-quantitativo: oposição ou complementaridade? Cad Saude Publ. 1993;9(3):239-62. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X1993000300002

28. Shelton CL, Smith AF, Mort M. Opening up the black box: an introduction to qualitative research methods in anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2014;69(3):270-80. doi: 10.1111/anae.12517

Correspondence to:

Correspondence to:

ARA LIMA

e-mail: alessandra.lima@saude.go.gov.br

Received on: 25/2/2014

Final version resubmitted on: 22/6/2014

Approved on: 10/7/2014