Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

RGO.Revista Gaúcha de Odontologia (Online)

versão On-line ISSN 1981-8637

RGO, Rev. gaúch. odontol. (Online) vol.64 no.1 Porto Alegre Jan./Mar. 2016

ORIGINAL / ORIGINAL

Ethical and moral development: aspects relating to professional training in Dentistry

Desenvolvimento ético e moral: aspectos relativos à formação profissional em Odontologia

Rayssa Pereira NACASATOI; Rafael Aiello BOMFIMI; Alessandro Diogo DE-CARLII

I Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul, Faculdade de Odontologia.

ABSTRACT

Objective

To assess the progression of a public university's dental students through stages of moral development during the course.

Methods

A cross-sectional study with 115 students (from the 1st to the 7th semester), to whom the "Opiniões sobre problemas sociais" test, adapted and translated to the Portuguese language, was applied.

Results

The collected answers were charted according to the test manual's guidelines and data were analyzed by the GraphPad Prism software 6.0 and STATA v.13. Principal morality score values, expressed as a P value (%), were 40.26%; 39.32%; 36.45% and 36.27% for the 1st, 3rd, 5th and 7th semesters, respectively, with no statistically significant difference between the groups (ANOVA, p = 0.52).

Conclusion

Students' degrees of morality did not vary significantly among the semesters compared, indicating the need for a reorientation of teachinglearning practices that takes the potential of transformative learning into account.

Indexing terms: Ethics. Curriculum. Higher education. Morals. Schools.

RESUMO

Objetivo

Avaliar a evolução nos estágios de desenvolvimento moral dos acadêmicos de Odontologia de uma Instituição Pública de Ensino Superior, ao longo da graduação.

Métodos

Estudo transversal com 115 acadêmicos (1º ao 7º semestre), em que foi aplicado o instrumento "Opiniões sobre problemas sociais", adaptado e traduzido para língua portuguesa.

Resultados

As respostas coletadas foram tabuladas de acordo com as orientações do manual do instrumento e os dados analisados pelo software GraphPad Prism 6.0 e no programa STATA v.13. Os valores do Principal morality score, expressos pelo valor de P (%), foram 40,26%; 39,32%; 36,45% e 36,27% para o 1º, 3º, 5º e 7º semestres, respectivamente, sem diferença estatística significante entre os mesmos (ANOVA, p=0,52).

Conclusão

O grau de moralidade dos estudantes não variou significativamente comparados os semestres em que os mesmos se encontravam, apontando a necessidade de reorientação das práticas de ensino-aprendizagem, considerando o potencial da educação transformadora.

Termos de indexação: Ética. Currículo. Educação superior. Princípios morais. Instituições acadêmicas.

INTRODUCTION

University training of health professionals, especially those in the field of dentistry, has been the object of much criticism due to the increasingly technical nature that has persisted for a long time. However, it has been observed that the purely scientific element has been unable to keep up with the modern demands of comprehensive, humanized patient care. Thus, a learning paradigm focusing on introspection and an academic curriculum that, besides theoretical knowledge, provides students with the ability to interact with psychological, social and philosophical issues related to dental practice, have been proposed1.

The establishment of the 1996 National Education Guidelines and Framework Law2 reflected the emergence of new trends, highlighting the importance of training technically capable and socially sensitive professionals. Despite controversy regarding the best methods for ensuring that dental surgeons graduate with this profile, studies exist that reinforce the need to invest efforts towards this goal and for training professionals who are citizens capable of making this a reality3-6.

One of the priorities in this period of adaptation of the educational context is the ethical dimension of professional training as, in order to train professionals to develop these characteristics, it is necessary, above all, to develop students' ethical and humanistic aspects with the aim of cultivating within them internal, critical reflection, beyond the imposed standards of and mere compliance with professional ethics4.

Thus, a strong curriculum in the fields of ethics and bioethics is required, one that presents students with the types of conflict that may be experienced within their professional routines, as discussing these issues during the course allows students to demonstrate integrity within professional practice, especially when confronted with situations that go beyond technical and scientific reason5-6.

Piaget's model illustrates a process of construction of morality that is organized hierarchically, in universal stages. Inspired by and extending this pioneering archetype of the study of moral development, as well as its educational applications, emerged the most prominent theoretical foundation of moral development, known as Kohlbergian theory. Bearing in mind its critical stance in relation to the classical standard of education, the method in question focuses on stimulating moral progress, encouraging the development of reasoning to sensitize the individual to the essence of the differences between people and their principles. This method of understanding moral development comprises a series of cognitive reorganizations that progress from one to another, going through six stages grouped into three levels7.

The pre-conventional level (stages 1 and 2) characterizes the individual attached to the social paradigms of right and wrong, linking the consequences of his/her actions to potential physical/material punishments or rewards. On the conventional level (stages 3 and 4), the individual shows an attitude of acceptance of and loyalty to the proposed order, in order to identify with the group and the people involved. On the post-conventional level (stages 5 and 6) it is mainly the subject that delineates moral values and the principles that have legitimacy and purpose, taking precedence, if necessary, over the sovereignty of the groups or people that maintain these principles7-8.

It is necessary to understand the development of this process in order to aid academic training in the fields of ethics and morality, stimulating effective educational interventions that avoid strict technicism and support a comprehensive education for the students, thereby contributing to the consolidation of a profile of the graduate as a citizen, in harmony with current National Curricular Guidelines9.

Thus, the objective of this study is to assess whether there are differences in the moral development of dental students attending public universities.

METHODS

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee, under opinion no. 320.360 (CAAE: 17016913.0.0000.0021).

A cross-sectional study was performed, in which all subjects were undergraduate students of the Faculty of Dentistry at Mato Grosso do Sul Federal University (UFMS) in 2013. The total number of participants was 150 (sample universe). Of these, 16 did not wish to participate and 19 were excluded for having transferred from other universities where they had already taken several classes; thus, the final number of student subjects in the study was 115 (n=115).

The Defining Issues Test 1 (DIT 1)10 was used in the present study, consisting of an objective test of moral judgment, translated and adapted for use in the Portuguese language under the title "Opiniões Sobre Problemas Sociais" (that is, Opinions On Social Problems), widely used in research in Brazil11.

The test consists of six moral dilemmas (John and the drug, Student occupation, The fugitive prisoner, The doctor's dilemma, The workshop owner, The newsletter) and, for each one of them, the subject must assess twelve possible answers, based on a five-level Likert scale, which ranges from "very important" to "not important"10.

To determine an individual's moral stage, it is not sufficient to assess the answers to one single story; it is necessary to observe and consider the whole set of dilemmas proposed in the test in order to establish consistencies in the subject's decisions8.

The assessed individual must also hierarchically select, among each of the dilemma's twelve options, the four that he/she considers the most important to its solution. Weightings of 4, 3, 2 and 1 are assigned, respectively, to the first, second, third and fourth most important options, in accordance with the test manual's guidelines10.

By means of this process, a P score (Principal morality score) is obtained, which may range from 0% to 95%, as established by the creators of the test. A postconventional level percentage (stages 5A, 5B and 6 of the DIT) that represents moral maturity is obtained, derived from the relative importance given by the participants to considerations guided by post-conventional principles in decision-making10.

Although the method provides quantitative results, qualitative analysis is possible due to the categorization of subjects into stages of moral development, attributing to the subjects of each group a maturity profile and development of reasoning that underpins their choice of ethical conduct12.

Data were collected in the classroom at UFMS. Average questionnaire application time was 30 minutes. At the point of application, verbal guidelines were given by the test administrator, with written guidelines on the cover sheet of the test, warning of the importance of paying close attention when answering the questions.

Prior to charting the questionnaires, assessments were conducted to detect incoherence or inconsistencies in the answers (an evaluation built into the test itself). This feature aims to minimize one of the DIT's weak points. As it is a self-reporting test, it is susceptible to the possibility of subjects answering randomly, without taking the appropriate care.

Following the manual's guidelines, questionnaires that had two or more stories with more than nine of the twelve options classified equally, with regard to importance, were discarded first. Next, those that showed inconsistencies, in two or more stories, among the options listed as the four most important and their classification of importance on the Likert scale, were discarded. Finally, questionnaires with M values greater than 8 were discarded, the M value representing answers with admirable rhetoric but lacking real sense. In other words, this score does not represent a stage of thought, but a tendency on the part of the subject to endorse moral positions out of presumption rather than because of their meaning10.

The data were charted in accordance with the test manual's instructions. The ANOVA test was performed using the GraphPad Prism 6.0® software, in order to compare average P scores between students in each semester and to measure the statistical significance of age differences among them. In addition, Cronbach's alpha test was performed with the STATA v.13® program in order to obtain the test's degree of reliability.

RESULTS

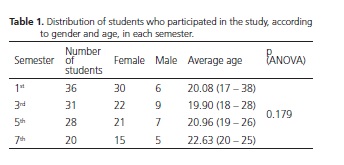

The students investigated in this research study are distributed by academic semester according to gender and age, as shown in Table 1.

Students' ages, among the groups studied, did not show any statistically significant difference, with p=0.179 according to the ANOVA test, as shown above.

The total number of discarded samples was 15 (13.04%), with a loss of 5-15% expected10, the total number of valid samples being 100. These samples were discarded in accordance with an analysis of response inconsistency, following the test manual's guidelines10.

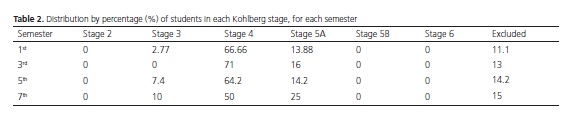

Assessment of the answers allowed for classification of the groups according to Kohlberg's moral stages. It was found that the vast majority of students were at the conventional level (stage 4) as shown in Table 2 below. After the data were charted, Cronbach's alpha test was applied, with a result of α =0.411.

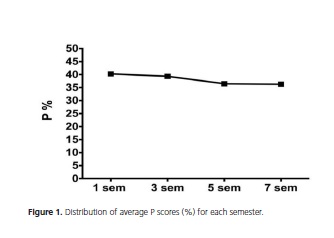

As for the P score (Principal morality score) measured in percentage terms, it was observed that the average value gradually decreased from the first to the last semester (Figure 1), although this reduction was not statistically significant (ANOVA, p=0.521). The P scores were 40.26%; 39.32%; 36.45% and 36.27%, for the 1st, 3rd, 5th and 7th semesters, respectively.

DISCUSSION

The assessment of issues pertaining to the moral development of students is of major importance to the process of transition that higher education is currently experiencing, considering the intricacies of curriculum design and the need to change them so that the National Curricular Guidelines9 can be addressed. So, although ethics and morality are generally presented as distinct concepts, they converge in the accumulation of the soft skills and competencies that permeate a student's development, within both the technical field and humanized health practices.

Although the reduction in P score was not statistically significant, its constancy can be seen and thus it is possible to suggest that the university, contrary to what has been proposed, has contributed very little to moral development and the maturation of soft skills in students, who are shown not to have covered the relevant aspects of the national curriculum during their training.

The slight variation in age among participants was considered constant as it was not statistically significant, and may be considered a factor that influences the stagnation of the morality index. However, it should be noted that, according to cognitive-evolutionary theory, age is considered an important element of reference, but is not a decisive factor in assessing individuals' quality of judgment or moral competence5,7-8.

On the other hand, variables related to this process indicate that academic experience, decision-making situations, clinical practice and connection with patients' reality usually favor the development of moral judgment5. However, this reality was not observed in this research.

The fact that the subjects of this study did not progress in their levels of moral development in a significant way, from the beginning to the end of the course, corroborates studies performed in several undergraduate courses such as: Pharmacy13, Law and Physical Education14 (a study comparing students in the respective courses), Teacher Training6, Psychology15, Dentistry16, Physical Therapy17 and Medicine5,18, demonstrating the widespread curricular issues in universities (with some exceptions) that continue to privilege technical and scientific aspects over encouraging other skills and abilities based on the humanities and social sciences.

Within the scope of Dentistry, the main factors that compromise students' perspectives of ethical and moral decisions in the academic environment are: concerns about minimum productivity demands of clinical procedures, rigorous evaluation methods with no feedback, lack of time in which to accomplish all assignments and a tense and competitive environment. This is worrying and challenging in terms of professional training, since Dentistry, as a health science, is related to life, human suffering and conflicting issues in society. Therefore, more important than denouncing unethical conduct is to create environments that discourage them, implementing a spirit of healthy teamwork and learning19.

Stage 4 of the study predominantly indicates a public driven by adherence to fixed rules and respect for authority, with little inclination towards critical reflection and changing reality7. These results clearly show a traditional training method rooted in deontological bases and partially explain the profile of an uncritical, unreflective undergraduate who is, to a certain extent, oblivious to reality, so common in Brazilian universities. These undergraduates are thus detached from their duty to serve society and to be professionals that can transform local reality and, consequently, have an impact on its demands4.

When one establishes that being ethical means to follow what is correct in order to maintain the status quo and to adopt professional codes in order to avoid being penalized, one establishes that ethics come from a source outside the individual, thus perpetuating outdated learning paradigms that currently do not allow for the advancement of problem-based and emancipatory education, which would encourage subjects to debate and confront ethical dilemmas4.

Thus, universities should encourage the development of ethical competence in future professionals, emphasizing autonomy of choices and decisions related to human beings and to caring for life and health in a critical, reflective and transversal way, overlaying already existing standards that are often stereotyped20. This is not being done at UFMS's Faculty of Dentistry, as the moral development (expressed as the P score) of 1st semester students was no different from that of 7th semester students.

In spite of this, we agree that the process of professional learning includes more than that which is set out in the formal curriculum. It also comprises the maxims of the hidden curriculum and, especially, influences from all social experiences within the teaching-learning process, in which the student is a protagonist and not an individual to be shaped by an institution. These hidden lessons are implicitly transmitted by educators during classroom routine, clinical activities and via their teaching methods, attitudes and choices5.

Students, during their experiences at university and via the hidden curriculum, build a series of subjective concepts, references and profession-related issues that will influence decision-making as well as their professional ethical conduct and social and interpersonal skills. These skills include the ability to deal with integrity, objectivity, public interest and social responsibility21. Soft skills approaches have been included, according to the needs of the population, in dentistry curricula in several countries, being considered important skills for the new dental surgeon profile, by institutions around the world22.

These factors need to be examined if we aspire to understand in what way the ethical training of students occurs, as they are intimately linked to moral education and the development of critical and reflective thinking in the context of higher education, which permeates the process of professional socialization23. In this way, it may be possible to make progress in the field of educational practices towards modifying the tendency towards the obsolete training that still persists in certain universities.

Moral development, included in an appreciation of each individual's particular characteristics and behavior, must be introduced into the ethical aspect of professional training. This provides autonomous thought that contributes to professional performance consistent with the development of a democratic and pluralistic society, focused on building more just and humanized social ties, taking the fairness and integrity of actions within healthcare into account23.

In this perspective, teaching's ethical component must be developed holistically, introduced into the various situations experienced during academic activities, with educators having the main responsibility for creating strategies and giving this reality an opportunity to thrive. Moreover, the academic curriculum itself should ensure the development of these skills right from the start of the course4-5,24.

It is important to note that teaching ethics and morality, in itself, does not generate appropriate conduct. To this end, these issues should not be approached in isolation, as mere curricular subjects, but in a constructive way throughout the course in all classes or learning modules, leading to introspection, self-reflection and self-awareness, which may stimulate commitment to the profession.

Therefore, it is important to cultivate ethics whose values are intrinsic, not just pre-established standards that must be met, so that teaching can foment the construction of new horizons and higher education fulfill its role as an agent that transforms society4.

This study's limitations included the reliability of the test (Cronbach's α) and the subjective and formative question of the subjects' ethical and moral component, which arises from the primary socialization that occurs in childhood and, therefore, also depends on issues relating to family and social groups.

Although Cronbach's α produced a value below that which is considered ideal, it does fall within the questionnaire's standards11. A relevant factor that undermines the test's internal reliability is related to the fact that assessment is restricted to the manual's constant guidelines. In this way, the order of selection of the stories' most important options may interfere, seeing that the same options, ranked differently, result in different scores and, therefore, a different classification of moral stage.

It is clear that promoting ethical and moral development is not just within the domain of the academic environment. On the contrary, this development is influenced by individuals' life stories, which are themselves subjective and diverse, resulting in different world views and, consequently, attitudes that are sometimes controversial. In this regard, one must take into account the formative components of family and social values (from religious, cultural and political points of view) which, along with higher education, contribute to this purpose.

However, university education can neither validate warped examples of conduct that society experiences, nor simply abstain from the discussion in a naïve attempt to ignore them, in order to remain neutral. It is essential to promote self-reflection, assess the challenges involved and propose adjustments where needed4,7.

Therefore, academic environments, even having just a partial role within this process, must transversely address the issue of approaching ethical and moral aspects in the curricular structure. In this way, students will be provided with learning opportunities and, possibly, opportunities for remodeling/revising attitudes towards situations experienced in society.

CONCLUSION

With this investigation, it was possible to observe how academic training, proposed by UFMS's Faculty of Dentistry, influences the construction of' the ethical and moral component of future professionals.

In conclusion, there was no progress in the levels of moral development among the study's subjects during the course. This fact indicates the need for a reshaping of teaching-learning practices with the aim of developing students' soft skills and competencies, which may have an impact on the profile of the undergraduate, taking into account the potential of transformative education.

Collaborators

RP NACASATO was responsible for the research project, data collection and writing the article. RA BOMFIM participated in the statistical analysis and writing the article. AD DE-CARLI supervised the research and took part in designing the study and writing the article.

REFERENCES

1. Whipp JL, Ferguson DJ, Wells LM, Iacopino AM. Rethinking knowledge and pedagogy in dental education. J Dent Educ. 2000;64(12):860-6. [ Links ]

2. Brasil. Lei n. 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996. Estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional. Diário Oficial da União. Brasília (DF); 1996 dez 24.

3. Freitas SFT, Kovaleski DF, Boing AF. Desenvolvimento moral em formandos de um curso de odontologia: uma avaliação construtivista. Cien Saude Colet. 2005;10(2):453-62. doi: 10.1590/S1413-81232005000200023

4. Finkler M, Caetano JC, Ramos FRS. Ética e valores na formação profissional em saúde: um estudo de caso. Cienc Saude Colet. 2013;18(10):3033-42. doi: 10.1590/S1413- 81232013001000028

5. Hren D, Marusic M, Marusic A. Regression of moral reasoning during medical education: combined design study to evaluate the effect of clinical study years. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e17406. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017406

6. Lepre RM, Shimizu AM, Bataglia PUR, Grácio MCC, Carvalho SMR, Oliveira JB. A formação ética do educador: competência e juízo moral de graduandos de pedagogia. Rev Educ Cultura Contemporânea. 2014;11(23):113-37.

7. Kohlberg L, Hersh RH. Moral development: a review of the theory. Theory Pract. 1977;16(2): 53-9.

8. Thoma SJ. Measuring moral thinking from a neo-kohlbergian perpective. Theory Res Educ. 2014;12(3):347-65. doi: 10.1177/1477878514545208

9. Brasil. Conselho Nacional de Educação. Câmara de Educação Superior. Resolução CNE/CES n. 3 de 19 de fevereiro de 2002. Institui diretrizes curriculares nacionais do curso de graduação em odontologia. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília (DF); 2002 mar 4; Seção 1.

10. Rest J. Manual for the Defining Issues Test. Center for the study of ethical development: University of Minnesota; 1986.

11. Bataglia PUR, Morais A, Lepre RM. A teoria de Kohlberg sobre o desenvolvimento do raciocínio moral e os instrumentos de avaliação de juízo e competência moral em uso no Brasil. Estud Psicol. 2010;15(1):25-32. doi: 10.1590/S1413- 294X2010000100004

12. Thoma SJ, Dong Y. The defining issues test of moral judgment development. Behavioral Develop Bull. 2014;19(3):55-61.

13. Prescott J, Becket G, Wilson SE. Moral development of first-year pharmacy students in the United Kingdom. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(2):1-5. doi: 10.5688/ajpe78236

14. Morais FA, Camino CPS. Desenvolvimento moral da justiça em estudantes dos cursos de direito e educação física da UFPB. Rev Tema. 2012;13(18-19):1-13.

15. Mattos GG, Shimizu AM, Bervique JA. A sensibilidade ética e o julgamento moral de estudantes de psicologia. Arq Bras de Psicol. 2008;60(3):113-28.

16. Freitas SF, Kovaleski DF, Boing AF, Boing AF, Oliveira WF. Stages of moral development among brazilian dental students. J Dent Educ. 2006;70(3):296-306.

17. Swisher LL. Moral reasoningamong physical therapists: result of the defining issues test. Physiother Res Int. 2010 Jun;15(2):69- 79. doi: 10.1002/pri.482.

18. Murrell VS. The failure of medical education to develop moral reasoning in medical students. Int J Med Educ. 2014;5:219-25. doi: 10.5116/ijme.547c.e2d1.

19. Divaris K, Barlow PJ, Chendea SA, Cheong WS, Dounis A, Dragan IF, et al. The academic environment: the students' perspective. Eur J Dent Educ. 2008;12(Suppl 1):120-30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600- 0579.2007.00494.x

20. Finkler M, Caetano JC, Ramos FRS. A dimensão ética da formação profissional em saúde: estudo de caso com cursos de graduação em odontologia. Cienc Saude Coletiva. 2011;16(11):4481-92. doi: 10.1590/S1413-81232011001200021

21. Abu Kasim NH, Abu Kassim NL, Razak AA, Abdullah H, Bindal P, Che' Abdul Aziz ZA, et al. Pairing as an instructional strategy to promete soft skills amongst clinical dental students. Eur J Dent Educ. 2014;18(1):51-7. doi: 10.1111/eje.12058

22. Cowpe J, Plasschaert A, Harzer W, Vinkka-Puhakka H, Walmsley AD. Profile and competences for the graduating european dentist – update 2009. Eur J Dent Educ. 2010;14(4):193-202. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2009.00609.x

23. Finkler M, Caetano JC, Ramos FRS. O cuidado ético-pedagógico no processo de socialização profissional: por uma formação ética. Interface Comunic Saude Educ. 2012;16(43):981-93.

24. Gerber VKQ, Zagonel IPS. A ética no ensino superior na área da saúde: revisão integrativa. Rev Bioét. 2013;21(1):168-78.

Correspondence to:

Correspondence to:

RP NACASATO

Cidade Universitária, Caixa Postal 549, 79070-900

Campo Grande, MS, Brasil

e-mail: rayssanacasato@yahoo.com.br

Received on: 16/8/2015

Final version resubmitted on: 26/9/2015

Approved on: 11/11/2016