Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

RGO.Revista Gaúcha de Odontologia (Online)

versão On-line ISSN 1981-8637

RGO, Rev. gaúch. odontol. (Online) vol.64 no.2 Porto Alegre Abr./Jun. 2016

ORIGINAL / ORIGINAL

Pregnant women's oral health: knowledge, practices and their relationship with periodontal disease

Conhecimentos e práticas de saúde bucal de gestantes e sua relação com doença periodontal

Luciana Luz Araújo de SOUSA I; Adriana CAGNANI I; Andréia Moreira de Souza BARROS I; Luciane ZANIN I; Flávia Martão FLÓRIO I

I Faculdade São Leopoldo Mandic, Curso de Odontologia, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Saúde Coletiva

ABSTRACT

Objective

To evaluate pregnant women's knowledge and perception of oral practices as well as their relationship with periodontal disease.

Methods

The project was developed in 27 units of the Family Health Strategy in the city of Picos, State of Piauí, Brazil, whose service prioritized providing the first dental appointment for pregnant women. A questionnaire was applied to 302 pregnant women, and a calibrated examiner (Kappa=0.96) performed the intraoral exam (CPI).

Results

the disease was present in 90.7% of them, although 96.4% had been to the dentist once, the majority have not seen a dentist during pregnancy, either because they feared the treatment would harm the baby, or lack of perceiving the need for doing so. Among those that had seen a dentist, did so because of pain or due to routine dental appointments. (19.9%). The belief that pregnancy could cause oral problems was mentioned by 39.7%, however, the majority (98.3%) stated they had received no guidance in this period, a fact which was shown to be associated with periodontal disease (p=0.0003).

Conclusion

It was concluded that there had been disease prevalence in the group, becoming persistent throughout pregnancy and also that the women presented many oral health care doubts during their gestational period.

Indexing terms: Oral health. Periodontal disease. Pregnancy.

RESUMO

Objetivo

Avaliar o conhecimento, as práticas e a percepção em saúde bucal de gestantes e a sua relação com a doença periodontal.

Métodos

Foi aplicado um questionário à 302 gestantes nas 27 unidades da Estratégia Saúde da Família de Picos, Piauí, cujo serviço priorizava apenas a realização da 1ª consulta odontológica na gestante. Examinadora calibrada (Kappa=0,96) realizou o exame intra-oral (IPC).

Resultados

A doença estava presente em 90,7% das gestantes, apesar de 96,4% delas já terem ido ao dentista alguma vez, a maioria não o fez na gestação, seja por medo de que o tratamento fizesse mal ao bebê, seja por ausência de percepção de necessidade. Dentre as que procuraram, o fizeram por dor ou busca por consultas de rotina. A crença de que a gravidez pode causar problemas bucais foi citada por 39,7%. A maioria das gestantes (98,3%) declarou não ter recebido orientações sobre como evitar problemas bucais e essa variável mostrou-se associada à presença da doença periodontal (p=0,003).

Conclusão

A doença periodontal é muito prevalente no grupo, persistindo durante a gestação e existem muitas dúvidas sobre os cuidados em saúde bucal durante o período gestacional.

Termos de indexação: Saúde bucal. Doenças periodontais. Gravidez.

INTRODUCTION

Pregnancy causes hormonal alterations which can lead to an increased risk of developing oral diseases1. These changes, such as increased levels of estrogen and progesterone and eating habits added to oral hygiene neglect can implicate in increased risk of diseases such as caries and periodontal disease2-3. In this period, maternal periodontitis has been associated with pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia, preterm birth and low birth weight4-5.

Dental treatment regarding pregnant women has still been surrounded by myths, beliefs and negative attributes causing them not to seek for care during this period. The main reasons were reported as follows: the uncertainty regarding treatment during pregnancy, risks concerning fetus formation and the low o perception of treatment needs. On top of these they also reported: fear of the dentist, the possibility of feeling pain and discomfort, the dental high speed drilling noise as well as the belief that pain is a pregnancy associated fact. All these are contributory issues which impair the search for dental treatment1,6. Added to this, some dentists' fear in assisting pregnant women cause these dental professionals to often postpone treatment for the post-natal period, which can lead to oral health deterioration and therefore injury both pregnant woman's and baby's health7.

Good interaction among the different professionals during prenatal care is of utmost importance in order to decide which the best intervention periods are and what procedures can be safely performed at each pregnancy period, including drug use8-9.

In the year 2000, Oral Health Teams (OHT) were incorporated into the Family Health Strategy (FHS) with the aim of providing better care, expanding health promotion, prevention and recovery of oral health. The Ministry of Health recommends pregnant women and children as priority groups and ensures prenatal care through qualified and humanized assistance10.

In order to make this possible, it is important to evaluate pregnant women's knowledge, habits and oral health, which will enable the setting of priorities and actions which can contribute to advise them as well as the professionals involved.

METHODS

This quantitative cross-sectional study was approved by the Research Ethical Committee of São Leopoldo Mandic Dentistry Faculty (2011/0.The study sample consisted of pregnant women assisted in the health units of the Family Health Strategy (FHS) in the municipality of Picos, State of Piaui, Brazil, located 310 km far from the State capital Teresina, which is the third largest city in the state. The Family Health Strategy, composed of 30 Family Health Teams, distributed in 27 units and 30 oral health teams, divided in 18 units covers all the city population. The research considered the 1039 pregnant women registered in April 2011 by the FHS teams.

The research included pregnant women aged between 18 and 35 years old, under prenatal care since the beginning of pregnancy and who agreed to participate and signed the free consent form. Excluding criteria consisted of: limitations to the examination, systemic alterations, not having at least 20 functional teeth and absence in the examination day.

Prior to data collection, a meeting with the nurse in charge and community health workers (CHW) was performed with the 30 teams distributed in 27 units in the city, in order to advise and state the research objectives and details.

In each of the units, the number of registered pregnant women who had attended prenatal care appointments was obtained, allowing for day-planning when the research would be carried out in each unit.

The sample was defined considering pregnant women's population enrolled in FHS, the 50% who participated, since this value provides the greatest degree of variance, 95% confidence level, 5% accuracy resulting in a minimum sample size of 280 pregnant women. The value of this rate was increased of 10% of no response and a sample size of 302 pregnant women was obtained. Based on information obtained in the meetings, the Family Health Units (FHU) were sorted in descending order of the number of pregnant women under follow-up.

The FHU were visited, in this descendent order, so that pregnant women could decide whether or not to participate in the study. The visits included 18 units for sample, 327 women were addressed. The criteria of inclusion and exclusion showed a sample of 302 pregnant women aged 18-35 years (24.6 ± 5.1 years).

An assessment questionnaire was used consisting of 33 questions which showed socioeconomic status, access to services, volunteers' awareness and oral health habits. The pregnant women answered the questions at the clinic before the oral examination and doubts were clarified by the researcher.

The periodontal examiner's training and calibration was performed with the participation of 20 volunteers who were evaluated twice, on different days, obtaining the intra-examiner Kappa value of 0.96.

After answering the questionnaire the patient was referred to the oral clinical examination, which was performed in the dental office at the Health Unit of each woman.

The periodontal evaluation was performed using the Community Periodontal Index (CPI) which shows the presence or absence of bleeding on probing, gingival calculus and deep periodontal pockets

If the index tooth was not present in the sextant, all the remaining teeth were examined and the highest score found was adopted for that sextant. According to the CPI hierarchical principle for the code 3 teeth should show bleeding and calculus, on the other hand for those classified as code 2, it is assumed the presence of bleeding11. The prevalence of pregnant women showing periodontal health was considered when the 6 index teeth presented CPI = 0. For the analysis, the CPI was dichotomized into CPI = 0 (periodontal health) and CPI≥1 (periodontal disease). To evaluate the need for treatment, the highest scores in the sextants were observed, and from there, the adequate treatment was pointed out.

After the tests, in each health unit, an educational lecture to the participants was carried out by the researcher, aiming to provide them with information about maternity-infantile oral health care. Pregnant women who had periodontal disease were referred for dental treatment with the oral health team at the health unit they belonged to.

Data were analyzed by means of frequency distribution tables, Chi-square or Fisher exact test where at least one of the frequencies was less than 5. For the purpose of the analysis the presence of periodontal disease in situations where there was at least one sextant with bleeding gums or periodontal pocket was considered. All analyzes were performed using SAS statistical software.

RESULTS

Periodontal health condition

It was found that only 11.6% (n = 35) of the women had CPI consistent with periodontal health and 45.7% (n = 138) of them had bleeding on probing. The other pregnant women showed the presence of dental calculus (29.8%; n = 90) and pouch with 4 to 5 mm (12.9%; n = 39).Oral hygiene orientation (CPI: 0 and 1) presented the highest demand as treatment needs are concerned and 57.3% of the pregnant women in the study should be treated.

Socio-demographic profile of pregnant women

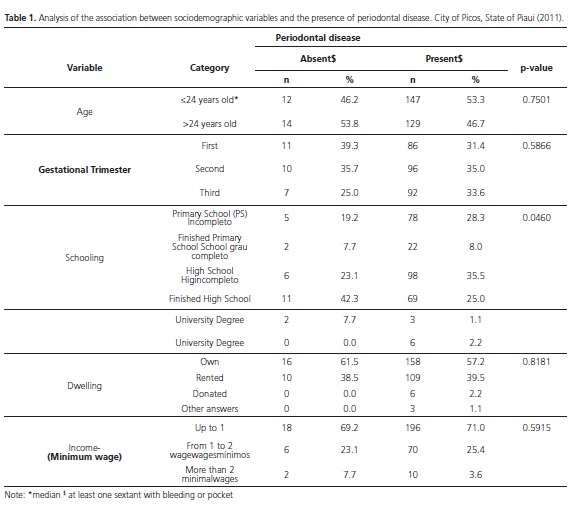

Table 1 shows the association analysis between sociodemographic variables and the presence of periodontal disease. It can be observed that among the variables tested, only schooling was associated with the presence of periodontal disease (p=0.0460).

Service access and oral health self-perception

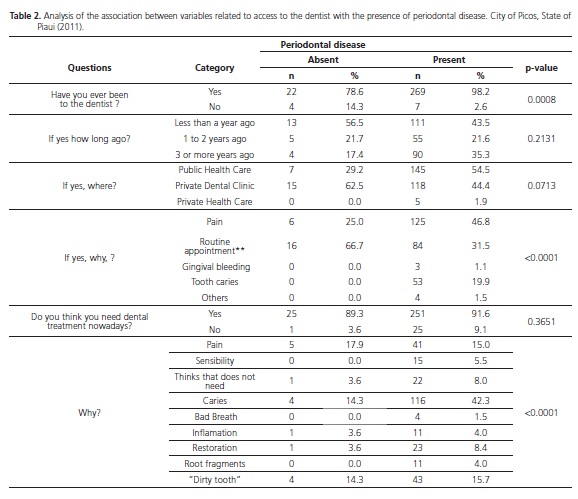

Table 2 shows the association between the variables related to seeking for dental treatment. The presence of periodontal disease was associated with the following variables: have been to the dentist at least once in life (p= 0.008) and reason for seeking treatment (p<0.0001). The main reasons reported were the presence of pain and search for ordinary dental treatment routines and restoration. During the appointment, the majority of pregnant women reported having not received guidance on oral health care.

As for their perception on the need for dental treatment, most stated they thought they needed some kind of treatment, variable which is associated with the presence of periodontal disease (p<0.0001).

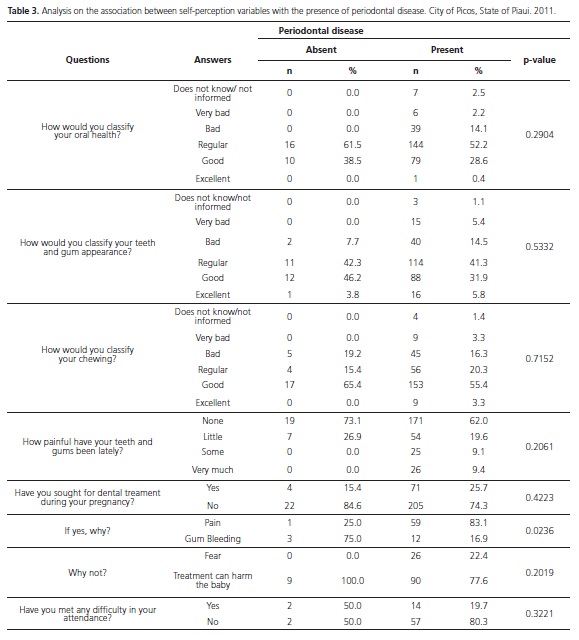

Table 3 presents the results of oral health selfperception and it can be observed that the presence of periodontal disease was not associated with the perception of oral health neither with issues such as teeth and gums condition or chewing.

Seeking for dental treatment due to pain or difficulties in having a dental appointment during pregnancy was not associated with the presence of disease. The fact that 74.2% of pregnant women did not seek care represents their low dental appointment attendance added to their fear that the dental treatment would harm the baby or the thought that they might not need any treatment. However among the women who sought for dental treatment it was not reported difficult access to it.

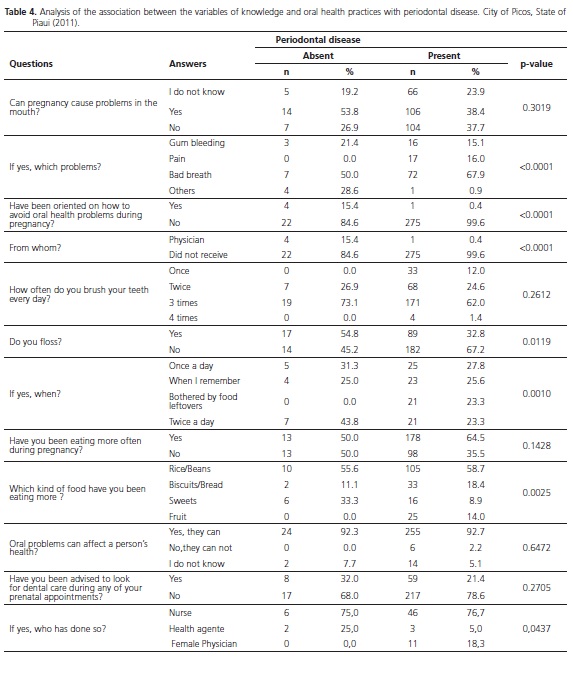

Oral health diseases of and perceptions of the pregnancy on oral health influence

Table 4 shows variables related to oral health knowledge and practices and it emphasizes that 39.7% of pregnant women reported to believe that pregnancy can cause oral health problems, including the bad breath (most cited). Periodontal disease was associated with the problems that would present relationship with the pregnancy (p<0.0001). Most patients (98.3%) stated that they had not received guidance on how to avoid dental problems and this variable was associated with the presence of periodontal disease (p<0.0001). Regarding self-care, most of them reported: brushing the teeth three times a day but not flossing. The absence of interproximal cleaning was associated with periodontal disease (p=0.0119). It was also reported an increase in the number of meals and the preference for high carbohydrate food.

The great majority of women (92.4%) believes that dental problems can affect a person's health, but they were not instructed to seek the dentist during the prenatal period.

DISCUSSION

Pregnant women care in the Family Health Strategy (FHS) in the municipality of Picos, State of Piaui (PI) follows the guidelines of the Program for Humanization of Labor and Delivery - PHLD, and the first registered prenatal pregnant women consultation should be held until the fourth month of pregnancy. At the time of the study (early 2012) dental care followed the guidelines of the Pact for Health10, since PHLD had not yet been deployed in the city. The service only prioritized the first dental appointment, and there was no effective follow-up for pregnant women dental treatment.

Dental care during pregnancy benefits both the mother's and the baby's quality of life6,9. However, pregnant women dental care does not yet merit the importance it deserves. Many factors such as their insecurity and dental treatment fear added to and the lack of health team interaction impair the fulfillment of women's health care during this period1,8.

Pregnancy brings women many physiological and psychological changes, demanding body adaptation during this new state. The oral health care during pregnancy is of utmost importance, although the majority of the population does not have knowledge of the oral changes inherent to this of períod13.

Periodontal disease proved to be prevalent in the population, in 88.4% of the women surveyed. This condition was also observed in other studies3,7 which highlight the fact that this a common oral change at this time. Interestingly, 75.5% of pregnant women presented mild disease, a situation that could have been controlled or even prevented by appropriate preventive measures applied during prenatal dental care.

Different schooling levels, socioeconomic profile, learning opportunities, can impact living and health conditions of the society .In the present study, schooling influenced the presence of periodontal disease affecting 71.8% of pregnant women who had not finished High School In the group who did not present the disease, 50% of them had at least finished High School.

The role of the dentist during dental prenatal care is essential in order to establish proper healthy habits and prevent oral disease, Among the assessed pregnant women, although most reported having consulted the dentist once in their lives, most of them (91.8%) did not seek the dentist during this pregnancy, which must be analyzed from different perspectives. In the Family Health Strategy (FHS), health professionals play an important role in the development of prenatal service care , providing specific guidance and advice for pregnancy and childbirth for the woman and her companion. However, multiprofessionality does not guarantee interdisciplinarity or project integration in the community14-17. Moura et al.18 found that in several municipalities of the State of Piaui the doctor and the dentist are not devoted enough in planning meetings, which may impair teamwork.

There are several psychological reasons that influence pregnant women's commitment to dental treatment added to admittance difficulties and care low perception5. The difficulty in using dental treatment is cited in other studies as the main reason for not seeking dental care during the gestational period9. This is not the same reality reported by pregnant women enrolled in the HFS at the city of Picos, State of Piaui, since among the few who sought care during pregnancy, very few reported attendance obstacles. Along with this, the low balance between seeking for public and private service, points to issues that may hamper the admittance of pregnant women to dental care in the FHS, such as the difficulty in scheduling appointments and service refusal to the pregnant patient by the surgeon dentist17.

Similar to literature, pain was the main reason reported by those pregnant women attending the service due to periodontal disease, although the majority reported not receiving dental guidelines on how to avoid oral health problems. The predominantly curative care and the lack of information as well as preventive measures hurt the Integrity principle in prenatal dental follow-up17. During pregnancy some predisposing conditions to periodontal disease are observed, including oral hygiene neglect and dietary changes. Therefore, educational hygiene practices and oral diseases prevention measures are essential. It was noted that among the pregnant women studied most of them reported either not knowing or not believing that pregnancy is likely to cause oral problems which suggests their lack of information about the common changes peculiar to this period thus confirming the need for oral health program with pregnant women19-20.

The lack of educational programs was identified during the analysis of pregnant women oral hygiene habits once most of them reported brushing their teeth three times or more, but did floss as a habit corroborating the Ramos et al.2. Regarding brushing, data should be carefully analyzed , since the dentist was present at the time the pregnant women answered the questionnaire, likely to have influenced the standard answer, widely reported in the media, regarding the frequency of tooth brushing.

Socio-economic conditions and the bodily experiences such as, weight gain and vomiting can interfere in pregnant women's nurturing. Among pregnant women in this study, the majority reported eating more frequently in pregnancy, especially the carbohydrate group of foods, which along with poor oral hygiene can affect periodontal health5.

Some oral pregnancy conditions may have negative outcomes for the child: periodontitis is associated with premature birth and low birth weight2 and preeclampsia. In the sample, the great majority of pregnant women reported knowing that oral diseases can affect the health and yet, few were instructed to seek dental treatment during prenatal, confirming previous reports that the assessment of oral health in pregnancy does not receive due attention.

Given the situation it could be seen that most of the assessed pregnant women had periodontal disease. Although they are aware that oral diseases can bring risks to their health, most of them have not received guidance to seek the dentist during pregnancy. This is consistent with the literature19 and highlights the fact that pregnant women have many doubts as well as dental needs, and should be more carefully taken care of by the dentists.

Obstetricians are professionals who have early contact with pregnant women, so it is important to emphasize the interaction between these professionals and dentists with guidelines for oral health and its effect on the baby, aiming at interdisciplinary targets. In many teams, the nurse,often unprepared concerning oral health, is the professional in charge of prenatal. Issues of core importance for pregnant women's health as a whole are as follows: enhancing the knowledge of all members of the family health team, bringing interdisciplinarity awareness, strengthening the bonds and overcoming barriers to dental care during pregnancy follow-up .

Dentists' behavior concerning pregnant women's care may result from fear of any harm to the mother or fetus and insecurities about procedures24. Following the performance of dentists in the Family Health Strategy in 19 municipalities in the State of Piaui, Moura et al.16 found that vocational training is still far from desired when it comes to the actual approach to the Unified Social System (USS) (a public service), as well as impairment regarding the continuing education of the professionals already involved in family health.

Health education in the actions taken by the USS becomes extremely important since it provides a link between all system management levels as well as a crucial tool to provide health policy and promotion. Through knowledge acquired in the process, families can confront the actions that have been performed over the years with new knowledge through health teams debates; thus as new concepts become assimilated and used in daily practice they will gradually be able to modify the actions and thoughts in order to promote beneficial and gradual changes in the surrounding environment6.

The prenatal period is the most suitable time for preventive action due to the fact that pregnant women are more willing and responsive to discussions and directly involved with the guidelines to be provided by the health professional about pregnancy and childbirth with a view also to the mother's role in the family.

It is observed that taking care of pregnant women's oral health, as well as pregnancy monitoring in all stages should be part of the routine of Oral Health Teams. Thus, the need to insert the dentist in Prenatal staff becomes mandatory, thus enabling oral health knowledge to flow throughout the entire team and answer questions about pregnant women's dental care. From the multi-professional integration, a comprehensive care of pregnant women through the development of educational and preventive actions throughout the pregnancy will be possible and will promote women's and baby's health.

CONCLUSION

A high prevalence of periodontal disease was observed in addition to many pregnant women's questions regarding oral health care during pregnancy, with no information increase concerning prenatal care.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful for the Support of São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) for the finantial aid granted.

Collaborators

All authors contributed substantially to the design and planning of the project, obtaining or analysis and interpretation of data, preparation or critical review of content and participation in the approval of the final version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

1. Alves RT, Oliveira AS, Leite ICG, Ribeiro LC, Ribeiro RA. Perfil epidemiológico e atitudinal de saúde bucal de gestantes usuárias do serviço público de Juiz de Fora, MG. Pesq Bras Odontoped Clin Integr. 2010;10(3):413-21. [ Links ]

2. Ramos TM, Almeida Júnior AA, Ramos TM, Novais SMA, Alves SM, Grinfeld S, et al. Condições de saúde bucal de gestantes e hábitos de higiene oral de gestantes de baixo nível sócioeconômico no município de Aracaju/SE. Pesq Bras Odontoped Clín Integr. 2006;6:229-35.

3. Monteiro RM, Scherma AP, Aquino DR, Oliveira AV, Mariotto AH. Avaliação dos hábitos de higiene bucal de gestantes por trimestre de gestação. Braz J Periodontol. 2012;22(4):90-9.

4. Assunção PL, Novaes HMD, Alencar GP, Melo ASO, Almeida MF. Fatores associados ao nascimento pré-termo em Campina Grande, Paraíba, Brasil: um estudo de caso-controle. Cad Saúde Pública. 2012;28(6):1078-90. doi: 10.1590/S0102- 311X2012000600007

5. Trevisan CL, Pinto AAM. Fatores que interferem no acesso e na adesão das gestantes ao tratamento odontológico. Arch Health Invest. 2013;2(2):29-35.

6. Codato LAB, Nakama L, Cordoni Júnior L, Higasi MS. Atenção odontológica à gestante: papel dos profissionais de saúde. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2011;16(4): 2297-301. doi: 10.1590/S1413-81232011000400029

7. Nascimento EP, Andrade FS, Costa AMDD, Terra FS. Gestantes frente ao tratamento odontológico. Rev Bras Odontol. 2012;69(1):125-30.

8. Costa IC, Saliba O, Moreira, AS. Atenção odontológica à gestante na concepção médico-dentista-paciente: representações sociais dessa interação. RPG - São Paulo. 2002;9(3):232-43.

9. Passini Júnior R, Nomura ML, Politano GT. Doença periodontal e complicações obstétricas: há relação de risco? Rev Bras Ginecol Obstret. 2007;29(7):372-7. doi:

10.1590/S0100- 72032007000700008 10. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Ações Programáticas Estratégicas. Prénatal e puerpério: atenção qualificada e humanizada: manual técnico. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2006 [citado 2013 Nov 10]. Disponível em: <http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/ manual_pre_natal_puerperio_3ed.pdf>.

11. Baelum V, Papapanou PN. CPITN and the epidemiology of periodontal disease Commentary. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1996;24(6):367-8.

12. Wandera MN, Engebretsen IM, Rwenyonyi CM, Tumwine J, Astrom AN, PROMISE-EBF Study Group. Peridontal status, tooth loss and self-reported periodontal problems effects on oral impacts on daily performances, OIDP, in pregnant women in Uganda: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Out. 2009;7:89. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-89

13. Bastiani C, Cota ALS, Provenzano, MGA, Fracasso MLC, Honório HM, Rios D. Conhecimento das gestantes sobre alterações bucais na gravidez e tratamento odontológico durante a gravidez. Odontol Clín-Cient. 2010;9(2):155-60.

14. Peres KG, Peres MA, Boing AF, Bertoldi AD, Bastos JL, Barros AJD. Redução das desigualdades na utilização de serviços odontológicos no Brasil entre 1998 e 2008. Rev Saúde Pública. 2012;46(2):250-9. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102012000200007.

15. Feldens EG, Feldens CA, Kramer PF, Claas BM, Marcon CC. A percepção dos médicos obstetras a respeito da saúde bucal da gestante. Pesq Bras Odontoped Clin Integr. 2005;5(1):41-6.

16. Moura CO, Aleixo RQ, Almeida FA, Silva HML, Moreira KFA. Prevalência de cárie em adolescentes gestantes relacionada ao conhecimento sobre saúde bucal em Porto Velho-RO. Saber Cient Odontol. 2010;1(1):1-20.

17. Santos Neto ET, Oliveira AE, Zandonade E, Leal MC. Acesso à assistência odontológica no acompanhamento pré-natal. Ciênc & Saúde Coletiva. 2012;17(11):3057-68. doi: 10.1590/S1413- 81232012001100022

18. Moura MS, Ferro FEFD, Cunha NL, Nétto OBS, Lima MDM, Moura LFAD. Saúde bucal na Estratégia de Saúde da Família em um colegiado gestor regional do estado do Piauí. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2013;18(2):471-80. doi: 10.1590/S1413- 81232013000200018

19. Moimaz SAS, Carmo MP, Zina LG, Saliba NA. Associação entre condição periodontal de gestantes e variáveis maternas e de assistência à saúde. Pesq Bras Odontoped Clin Integr. 2010;10(2):271-8.

20. Maia AS, Silva PCS, Almeida MEC, Costa AMM. Percepção de gestantes do Amazonas em relação à saúde bucal. ConScientiae Saúde. 2007;6(2):377-83.

21. Baião MR, Deslandes SF. Gravidez e comportamento alimentar em gestantes de uma comunidade urbana de baixa renda no município do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2008;24(11):2633-42. doi: 10.1590/S0102- 311X2008001100018.

22. Offenbacher S, Boggess KA, Murtha AP, Jared HL, Lieff S, McKaig RG, et al. Progressive periodontal disease and risk of very preterm delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(1):29-36.

23. Canakci V, Canakci CF, Canakci H, Canakci E, Cicek Y, Ingec M, et al. Periodontal disease as a risk factor for preeclampsia: a case control study. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;44(6):568-73.

24. Michalowicz BS, DiAngelis AJ, Novak MJ, Buchanan W, Papapanou PN, Mitchell DA, et al. Examining the safety of dental treatment in pregnant women. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139(6):685-95. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0250.

Correspondence to:

Correspondence to:

FM FLORIO

Rua José Rocha Junqueira, 13, Swift

13045- 755

Campinas, SP, Brasil

e-mail: flaviaflorio@yahoo.com

Received on: 9/9/2015

Final version resubmitted on: 22/12/2015

Approved on: 1/3/2016