Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

RGO.Revista Gaúcha de Odontologia (Online)

versão On-line ISSN 1981-8637

RGO, Rev. gaúch. odontol. (Online) vol.64 no.3 Porto Alegre Jul./Set. 2016

REVISÃO / REVIEW

Longevity of restorations in direct composite resin: literature review

Longevidade de restaurações diretas em resina composta: revisão de literatura

Marilia Mattar de Amôedo Campos VELOI; Livia Vieira Braga Ferraz COELHOII; Roberta Tarkany BASTINGII; Flávia Lucisano Botelho do AMARALII; Fabiana Mantovani Gomes FRANÇAII

I Universidade de São Paulo, Faculdade de Odontologia

II Faculdade São Leopoldo Mandic, Curso de Odontologia, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Odontologia. Campinas, SP, Brasil

ABSTRACT

Composite resin restorations have increased considerably in popularity and predictability, enabling the realization of a minimally invasive dental treatment. However, to obtain the success of composite resin restorations, knowledge of adhesives and the use of the technique are required, otherwise failure may appear quickly. The objective of the present work was to conduct a literature review on the clinical performance of different types of composite resins and adhesive systems with regard to longevity. For this evaluation, some characteristics of the restorations were immediately verified after they were completed and after a determined time. Characteristics such as postoperative sensitivity, color, marginal integrity, secondary caries, texture, marginal adaptation, retention, displacement, marginal discoloration and anatomical shape had their performances compared. The influence of different adhesive systems on the longevity of the restorations was also observed as a function of its fundamental importance in the union between the tooth and the restorative material. It was concluded that most restorations performed clinically acceptable when hybrid, nanoparticle or microhybrid composite resins and conventional adhesive systems were used.

Indexing terms: Clinical evolution. Composite resins. Dental restoration permanent.

RESUMO

As restaurações de resinas compostas têm aumentado consideravelmente em popularidade e previsibilidade, possibilitando a realização de um tratamento odontológico minimamente invasivo. No entanto, para se obter o sucesso das restaurações de resina composta é necessário ter conhecimento dos materiais adesivos e da técnica de utilização, caso contrário os insucessos podem aparecer rapidamente. Assim, o objetivo deste trabalho foi realizar uma revisão de literatura sobre o desempenho clínico de diferentes tipos de resinas compostas e de sistemas adesivos no que se refere à longevidade. Para essa avaliação foram verificadas algumas características das restaurações logo após elas serem finalizadas e depois de um determinado tempo. Características como sensibilidade pós-operatória, cor, integridade marginal, cárie secundária, textura, adaptação marginal, retenção, deslocamento, descoloração marginal, forma anatômica, tiveram seus desempenhos comparados. A influência dos vários sistemas adesivos na longevidade das restaurações foi também observada em função da sua fundamental importância na união entre o dente e o material restaurador. Concluiu-se que a maioria das restaurações se apresentou clinicamente aceitável, quando se usou resinas compostas híbridas, nanoparticuladas ou microhíbridas e sistema adesivo convencional.

Termos de indexação: Evolução clínica. Resinas compostas. Restauração dentária permanente.

INTRODUCTION

Composite resin restorations have increased considerably in popularity and predictability, becoming routine in dental practice1. Some reasons for this development was the possibility of a minimally invasive dental treatment, improvement in the development of resins and adhesive restorative techniques and an increase in the number of patients who seek aesthetic restoration to replace the amalgam2 and in that context, composite resin has been widely used for this type of procedure, reaching a high-level of restorations obtained because of their physical and aesthetic properties. However, to achieve success with composite resin restorations, knowledge of the restorative and adhesive materials and the use of appropriate technique are required, otherwise failure may occur quickly3.

Among the diverse classifications of resins, the most widely used is the one that refers to the size of the particles, which are divided into macroparticles, hybrids, micro-hybrids, microparticles, nanoparticles, and nanohybrids4. The macroparticle and microparticle resins were only indicated for anterior teeth. However, with the development of hybrid resins with improved wear resistance1, there has been increased interest in using this type of resin in posterior teeth5.

In this context, nanotechnology has allowed the development of resins with excellent mechanical and aesthetic properties related to good polishing and less shrinkage6, and may be employed both in anterior teeth as well as posterior teeth7. Thus, the microhybrid, nanohybrid and nano particle composite resins are considered universal in use and are also indicated for the restoration of posterior teeth.

In addition to the knowledge on the characteristics of the restorative resin material to be used, the adhesion of composite resins to hard tissues is of fundamental importance for the longevity of restorations8. Adhesion occurs mainly by the formation of a hybrid layer between the adhesive systems and enamel and/or dentin9. The adhesive systems present themselves differently and also act with different adhesive strategies which can be acid conditioned with adhesives with two or three application steps or by the use of self- etching systems that incorporate a one or two step application10.

Although the insertion techniques and performance of composite resins are increasingly widespread among professionals, some authors question what is the best resin for their restorations, ie, which has the best clinical performance and longevity. Some of the features taken into consideration for the present evaluation are post-operative sensitivity, recurrent decay, shade stability, marginal integrity, anatomic form, marginal discoloration, surface texture, retention, detachment and marginal adaptation of restorations11.

The aim of the present study was to determine whether differences exist in the literature with regard to longevity and maintenance of the characteristics between the different types of composites, also taking into account the adhesive systems employed.

LITERATURE REVIEW AND DISCUSSION

Classification of composites

Developments in restorative procedures provided by the advent of adhesive systems have changed the landscape in dental practice. More conservative procedures made possible by the possibility of bonding the restorative material to the dental substrate and the current search for aesthetic procedures also in posterior teeth makes composite resin the material of choice in many clinical situations12. However, the use of this material occurred only because of its improvement, which led to improvements in their mechanical properties, making it more resistant to masticatory forces5.

Among the diverse classifications of composite resins, the most used is relative to the size of theis particles, being divided into macroparticles, hybrids, microhybrids, microparticles, nanoparticles and nanohybrids4.

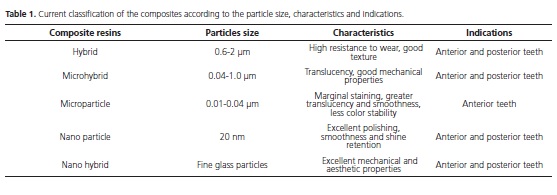

The first composite resins were named macroparticle resins because they had large charge particles around 8 to 50 microns, usually quartz and were activated chemically. Due to the size of the particles, some drawbacks were presented such as enhanced wear resulting in easy detachment of the particles, resulting in high surface roughness and staining. For not having appropriate mechanical properties, this group of resins was intended only for anterior teeth5,13, however, due to the evolution of materials, they are no longer used. In order to decrease the surface roughness, microparticle resins were developed, having particles ranging from 0.01 μm to 0.04 μm, presenting smaller and greater shade stability and marginal staining, or very smooth and translucent and are indicated for anterior teeth and reproduce the enamel14 well possessing properties such as resistance to wear and inferior flexion when compared with other resins (Table 1).

Hybrid resins have two types of charged particles (silica and glass particles), with sizes ranging from 0.6 to 2 μm, which enabled an improvement in the physical properties of the material with high wear resistance and good texture. The association of the microparticle resins (suitable for anterior teeth) to the hybrid resin has spurred the microhybrid resins, providing a more aesthetic and resistant material than the previous ones (Table 1). Microhybrids can be considered a subdivision of hybrid and have translucency, allowing proper polishing for reproducing enamel in the anterior teeth as well as having a higher ratio between the load and matrix, which allowed an improvement in mechanical properties, making them able to restore posterior teeth15. They also have different viscosities due to the varying amount of load, and as examples, there are the flow and condensable resins16 (Table 1).

Nanotechnology allowed the production of resins with excellent polishing and mechanical properties and lower shrinkage17 that have particles of 5 to 20 nm in size, providing good polishing, surface smoothness and gloss retention and high resistance to abrasion. The inorganic loading with silica and zirconia leads to a similar performance to microhybrid resins in relation to the mechanical properties on posterior teeth, similar to the microparticle resins regarding aesthetics in the anterior teeth18. In addition to the nanoparticle resins, there are also resins composed of nanohybrids that incorporate nanoparticles in the microhybrid resins and are considered universal since they have properties suitable for both the anterior teeth as well as the posterior teeth, due to the mechanical and aesthetic properties they present19 (Table 1). In general, composite resins with microhybrid, nanohybrid and nanoparticles are mainly used20.

Longevity of restorations in composite resin

Based on the characteristics and properties provided by the composite resins, it is possible to choose the ideal material for each type of situation. However, for a restoration to be considered satisfactory, it is necessary in addition to understanding the material properties to become familiar with the techniques of cavity preparation, respecting the protocols of the materials used and then obtain the clinical success of the restorations12.

Regarding the longevity of composite resin restorations, there is still no clear understanding of the clinical factors that can influence the performance of the restorations. Additionally, some patient-related factors are those that most influence in the long run, such as diet, oral hygiene, parafunctional habits and occlusion. Some clinical trials were performed to evaluate the longevity of composite resin restorations and showed great limitations due to the reduction in the number of patients in each call for reevaluation21. In these studies, Class I, II, III and V restorations were carried out with composite resin of several trademarks, mostly microhybrid. The restorations were deemed valid or with practical and aesthetic clinical success since they were not repaired or replaced during the study period22. The results showed variations of repairs or replacements of one to five years according to each case, mostly between two and three years.

Success and clinical failure of the restorations must be evaluated according to the modified Ryge criteria23, which are defined by the parameters of evaluation of marginal adaptation, anatomic form, surface roughness, proximal and occlusal contacts, postoperative sensitivity, and the presence of secondary caries in resin restorations. In addition to the Ryge criteria, it was used photographs and plaster replicas24 and it was used as evaluation criteria, the modified rules of the US Public Health Service (USPHS)25.

The modified USPHS system has been widely used in clinical trials and their evaluation criteria show very reliable results. In 2014, it was conducted26 a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the performance over a period of a year of two direct composite resins in posterior teeth using the modified USPHS system. The results of this evaluation showed that most of the failures were associated with the marginal fit and integrity of the material.

Another study27 evaluated the longevity of conventional composed resins during a period of 27 years in posterior restorations (Class II), and the evaluation criteria were also performed by the modified USPHS system. In a total of 30 participants, postoperative sensitivity was observed in 5 patients. The overall success rate of the restorations was 56.5%, with an annual failure rate of 1.6%. The study showed that the main reason for the failure of the restorations was the development of secondary caries, followed by occlusal wear and fracture of the material. However, the study concluded that conventional composite resins had an acceptable success rate during the 27-year evaluation period.

Due to the variety of resin composites on the market, many comparisons were made between them. A recent systematic review of the literature, which included clinical trials with evaluation of at least two years of longevity showed that secondary caries was common in most studies and that the resin restorations for Class III cavities succeeded 95% and Class IV 90%, being the dental fracture of Class IV restorations the main reason of failure. Regarding the comparison of the types of resin, the hybrid composite resin demonstrated a better performance in that systematic review when compared to the other composites12.

In evaluating the longevity of restorations with resin, it was essential to consider the characteristics that affect the clinical outcomes, especially the properties of the restorative material, since in those studies, the recommendations of the manufacturer were followed most of the time28, It was found that the use or not of a flowable adhesive between the system and the resin did not affect the survival rate of the restorations29. The reasons for failure were defects in the margin of adaptation, secondary caries, fracture and surface finish degradation. In 2006, it was reported a 9% rate of compactable composite fractures within three years of their study30, while another study valuated four compactable composites for a year, reporting fracture in the marginal ridge in 1% of the restorations made of the same resin (Filtek Supreme)31. It was found an increased risk of fracture in large Class II restorations since 25% of the restorations with Solitaire resin showed fractures in the marginal ridges24. Fractures on the crests were justified by inadequate healing in the deeper areas of the restorations29.

Also in this topic, the clinical performance of the Universal adhesive system used in the conventional mode and self-adhesive mode was tested in non-cervical carious lesion restorations32 compared to the three step conventional adhesive system (Scotchbond), considered the gold standard adhesive system in the literature. The composite resin restorations were evaluated in the periods of 6,12 and 24 months in relation to the marginal adaptation, marginal discoloration, presence of secondary caries and sensitivity to cold by the modified USPHS criteria. Over time, lower clinical performance of all materials tested in the marginal adaptation and discoloration was noted. However, the Universal system when using conventional or self-etching adhesives presented better results and better clinical performance than the Sotchbond32.

Another factor that should be considered in evaluating the longevity of composite resin restorations is the presence of secondary caries and marginal leakage caused by bacteria passing through the interface tooth/restoration. The amount of enamel in the cervical wall interferes with the sealing because if there is less enamel, the adhesion process is most affected. This is confirmed in the study, which only observed a restoration with secondary caries in a tooth, in which the end was in the dentin after two years29. However, the two restorations that failed in the study by Poon24 were presented by secondary caries in the proximal region, being an area of difficult cleaning. The study of Lawson32, when the restorations close to the cervical region were performed with the Universal system before insertion of the composite resin, a lower rate of marginal discoloration and bacterial infiltration were observed.

In relation to the retention rate and displacement of restorations, studies were done comparing different types of adhesive systems. It was compared the fourth and fifth generation of adhesives and found satisfactory performance in Class I and II cavities28. For self-etched adhesives, it was found that when using four layers instead of two, the successful retention of Class V restorations greatly increased9. In another study33, three self-etching and one monolithic conventional (control) adhesives were evaluated, it was found that only the One-Step Plus (conventional) gave a good marginal fit, and the iBond (selfetching) had a poor performance. The performance of selfetching adhesive systems could have been worse due to the presence of high concentrations of ethanol and water in their composition, which compromises the polymerization of monomers into the demineralized dental substrate9.

In the studies by Demirci34, restorations made with microparticle resins with a single bottle of water-based and alcohol adhesive (Single Bond) and a conventional adhesive with a single acetone based bottle (Prime and Bond NT) showed that color-related problems were found in 3.6% of the restorations in all groups, demonstrating similar results for different types of resins. Another study9 evaluated for three years, four compactable composite resins in Class I and II posterior teeth and compared to a hybrid resin. The hybrid resin (TPH Spectrum) showed 50% discoloration of the restorations, which was not verified with those made with Surefill and Filtek P60. It was observed35 in the restorations with single step adhesive (Adper Prompt L-Pop) and nanoparticle resin (Filtek Supreme), a significant marginal discoloration in the sixth month evaluation that did increase in the fifteen month evaluation. A relevant change in the color due to the composition of each resin also depends on each manufacturer. The microparticle resins alter the color more than the hybrids due to the large amount of organic matrix as well as the macroparticle resins by the weak bond between the organic matrix and the inorganic load by the silane, and hybrid resins have better clinical performance1,35.

A very important factor for the longevity of the restoration is also the finish and final polish. A study was able to detect distinct areas of surface roughness and slight discoloration, and small surface defects appeared to have been caused by dental instruments for finishing and polishing of restorations, but the results were assessed as satisfactory24. In terms of surface texture and marginal discoloration, two compactable resins exhibited similar behavior. This finding has been attributed to the fact that both resins have a similar load size2, However, the compactible hybrid resins, because they have more amounts of inorganic charge, present inferior polishing and finishing2.

With regards to the insertion technique, it is suggested that the resins are placed in oblique incremental layers, because it reduces the effect of polymerization shrinkage stress in the adhesive interface, thereby reducing the chances of sensitivity caused by intercuspal voltage24. Wilson et al.21 obtained 100% absence of sensitivity using a composite resin associated with a self-etching adhesive, used incrementally.

Comparing various types of composite resins, it was found that a compactable resin has satisfactory clinical performance, similar to microhybrid and nanoparticle resins when placed in Class I cavities following the rules of the respective manufacturer4,9 however, the nanoparticle and microhybrid resins had slightly better results4.

However, nanoparticle resins, due to their large percentage of inorganic load, have low polymerization shrinkage and because of the size of the particles, have excellent polishing. This new generation of composite resin can certainly be used in both anterior and posterior teeth due to the superior mechanical and aesthetic properties they possess7. In general, today composite resins with microhybrid, nanohybrid and nano particles are mainly used.

CONCLUSION

The present literature review shows that the clinical performance of composite resins used as permanent restorative material is satisfactory and can be indicated safely, given the clinical trials recorded in the period between 1 and 5 years. However, the clinical steps of applying adhesive systems, insertion of the restorative material and curing should be performed with caution, respecting the manufacturer's recommendations. In addition, much more information is necessary to minimize the effects of each oral environment from each patient on a resin restoration.

Collaborators

MMAC VELO and LVBF COLEHO wrote the paper. RT BASTING and FLB AMARAL wrote and critically revised the paper before its submission. FMG FRANÇA supervised the experimental, performed the study design and critically revised the paper.

REFERENCES

1. Heintze SD, Rousson, V. Clinical effectiveness of direct class II restorations: a meta-analysis. J Adhes Dent. 2012;14(5):407-431. doi: 10.3290/j.jad.a28390 [ Links ]

2. Fagundes TC, Barata TJ, Bresciani E, Cefaly DF, Jorge MF, Navarro MF. Clinical evaluation of two packable posterior composites: 2-year follow-up. Clin Oral Investig. 2006;10(3):197-203. doi: 10.1007/s00784-006-0059-y

3. Miyashita E, Mello AT. Odontologia estética: planejamento e técnica. São Paulo: Artes Médicas; 2006.

4. Sadeghi M, Lynch CD, Shahamat N. Eighteen-month clinical evaluation of microhybrid, packable and nanofilled resin composites in Class I restorations. J Oral Rehabil. 2010;37(7):532- 7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2010.02073.x

5. Nagem Filho H, Nagem HD, Fares NH. Materiais dentários: resinas compostas. São José dos Pinhais: Plena; 2011.

6. Pereira RA, Araujo PA, Castaneda-Espinosa JC, Mondelli RFL. Comparative analysis of the shrinkage stress of composite resins. J Appl Oral Sci. 2008;16(1):20-34. doi: 10.1590/S1678- 77572008000100007

7. Koottathape N, Takahashi H, Iwasaki N, Kanehira M, Finger WJ. Two- and three-body wear of composite resins. Dent Mater. 2012;28(12):1261-70. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2012.09.008

8. De Munck J, van Landuyt K, Peumans M, Poitevin A, Lambrechts P, Braem M, et al. A critical review of the durability of adhesion to tooth tissue: methods and results. J Dent Res. 2005;84(2):118-132. doi: 10.1177/154405910508400204

9. Loguercio AD, Reis A. Application of a dental adhesive using the self-etch and etch-and-rinse approaches: an 18-month clinical evaluation. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139(1):53-61. doi: 10.14219/ jada.archive.2008.0021

10. Perdigão J, Dutra-Corrêa M, Anauate-Netto C, Castilhos N, Carmo AR, Lewgoy HR, et al. Two-year clinical evaluation of self-etching adhesives in posterior restorations. J Adhes Dent. 2009;11(2):149- 59.

11. Burke FJ, Crisp RJ, Balkenhol M, Bell TJ, Lamb JJ, McDermott K, et al. Two-year evaluation of restorations of a packable composite placed in UK general dental practices. Br Dent J. 2005;199(5):293- 6. Doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4812654

12. Heintze SD, Rousson V. Clinical effectiveness of direct class II restorations: a meta-analysis. J Adhes Dent. 2012;14(5):407-31. doi: 10.3290/j.jad.a28390

13. Anusavice KJ, Phillips D. Materiais dentários. 11ª ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan; 2005.

14. Mahmoud SH, El-Embaby AE, AbdAllah AM, Hamama HH. Twoyear clinical evaluation of ormocer, nanohybrid and nanofill composite restorative systems in posterior teeth. J Adhes Dent. 2008;10(4):315-22.

15. Souza FB, Guimarães RP, Silva CH. A clinical evaluation of packable and microhybrid resin composite restorations: one-year report. Quintessence Int. 2005;36(1):41-48.

16. Torres CR, Borges AB, Goncalves SE, Pucci CR, de Araujo MA, Barcellos DC. Clinical evaluation of two packable resinbased composite restorations: a three-year report. Gen Dent. 2010;58(4):338-343.

17. Terry DA. Direct applications of a nanocomposite resin system: Part 1--The evolution of contemporary composite materials. Pract Proced Aesthet Dent. 2004;16(6):417-22.

18. Efes BG, DorterC, Gomes Y. Clinical evaluation of an ormocer, a nanofill composite and a hybrid composite at 2 years. Am J Dent. 2006;19(4):236-240.

19. Celik C, Arhun N, Yamanel K. Clinical evaluation of resin-based composites in posterior restorations: 12-month results. Eur J Dent. 2010;4(1):57-65.

20. Ferracane JL. Resin composite--state of the art. Dent Mater. 2011 Jan;27(1):29-38. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2010.10.020.Wilson

21. Wilson NH, Gordan VV, Brunton PA, Wilson MA, Crisp RJ, Mjör IA. Two-centre evaluation of a resin composite/ self-etching restorative system: three-year findings. J Adhes Dent. 2006 Feb;8(1):47-51. doi:10.3290/j.jad.a10899

22. Manhart J, Chen HY, Neuerer P, Thiele L, Jaensch B, Hickel R. Clinical performanc e of the posterior composite QuiXfil after 3, 6, and 18 months in Class 1 and 2 cavities. Quintessence Int. 2008; 39(9):757-65.

23. Burke FJ, Crisp RJ, Balkenhol M, Bell TJ, Lamb JJ, McDermott K, et al. Two-year evaluation of restorations of a packable composite placed in UK general dental practices. Br Dent J. 2005;199(5):293- 6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4812654

24. Poon EC, Smales RJ, Yip KH. Clinical evaluation of packable and conventional hybrid posterior resin-based composites: results at 3.5 years. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005; 136(11):1533-40. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2005.0083

25. Fagundes TC, Barata TJ, Bresciani E, Cefaly DF, Jorge MF, Navarro MF. Clinical evaluation of two packable posterior composites: 2-year follow-up. Clin Oral Investig. 2006;10(3):197-203. doi: 10.1007/s00784-006-0059-y

26. Beck F, Dumitrescu N, König F, Graf A, Bauer P, Sperr W, et al. Oneyear evaluation of two hybrid composites placed in a randomizedcontrolled clinical trial. Dent Mater. 2014; 30(8):824-838. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2014.05.006

27. Pallesen U, van Dijken JW. A randomized controlled 27 years follow up of three resin composites in Class II restorations. J Dent. 2015 Dec;43(12):1547-58. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2015.09.003

28. Gallo JR, Burgess JO, Ripps AH, Walker RS, Winkler MM, Mercante DE, et al. Two-year clinical evaluation of a posterior resin composite using a fourth- and fifth-generation bonding agent. Oper Dent. 2005;30(3):290-6.

29. Sarrett DC, Brooks CN, Rose JT. Clinical performance evaluation of a packable posterior composite in bulk-cured restorations. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006; 137(1):71-80. doi: 10.14219/jada. archive.2006.0024

30. Ernst CP, Brandenbush M, Meyer G, Canbek K, Gottschalk F, Willershausen B. Two-year clinical performance of a nanofiller vs a fine-particle hybrid resin composite. Clin Oral Investig. 2006;10(2):119-25. doi: 10.1007/s00784-006-0041-8

31. Dresch W, Volpato S, Gomes JC, Ribeiro NR, Reis A, Loguercio AD. Clinical evaluation of a nanofilled composite in posterior teeth: 12-month results. Oper Dent. 2006;31(4):409-417. doi: 10.2341/05-103

32. Lawson NC, Robles A, Fu CC, Lin CP, Sawlani K, Burgess JO. Two-year clinical trial of a universal adhesive in total-etch and self-etch mode in non-carious cervical lesions. J Dent. 2015 Oct;43(10):1229-34. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2015.07.009

33. Perdigão J, Dutra-Corrêa M, Anauate-Netto C, Castilhos N, Carmo AR, Lewgoy HR, et al. Two-year clinical evaluation of self-etching adhesives in posterior restorations. J Adhes Dent. 2009;11(2):149- 59. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2015.07.009

34. Demirci M, Yildiz E, Uysal O. Comparative clinical evaluation of different treatment approaches using a microfilled resin composite and a compomer in Class III cavities: two-year results. Oper Dent. 2008;33(1):7-14. doi: 10.2341/07-34

35. Manchorova NA, Vladimirov SB, Donencheva ZK, Drashkovich IS,Manolov SK, Todorova VI. Clinical evaluation of restorations with self-etch adhesive and nanofilled composite in class I and class II cavities. Folia Med (Plovdiv) 2008;50(1):46-52.

Correspondence to:

Correspondence to:

MMAC VELOAl

Dr. Octávio Pinheiro Brisolla, 9-75, Vila Nova, Cidade Universitaria

17012-901, Bauru, SP, Brasil

e-mail: mariliavelo@yahoo.com.br

Received on: 1/2/2016

Final version resubmitted on: 15/3/2016

Approved on: 27/3/2016