Services on Demand

Article

Related links

Share

RSBO (Online)

On-line version ISSN 1984-5685

RSBO (Online) vol.9 n.1 Joinville Jan./Mar. 2012

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE

Evaluation of the psychological factors and symptoms of pain in patients with temporomandibular disorder

Wilkens Aurélio Buarque e Silva I ; Frederico Andrade e Silva I ; Milene de Oliveira I ; Silvia Maria Anselmo I

I Department of Prosthesis and Periodontics, School of Dentistry of Piracicaba, State University of Campinas – Piracicaba – SP – Brazil.

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The influence of psychological factors on temporomandibular disorders (TMD), such as depression, anxiety and stress has been very discussed in literature. However, there is no consensus about their influence on the clinical manifestation of TMD. Objective: To evaluate the evolution of minor psychiatric disorders and pain symptoms in patients with temporomandibular disorders (TMD) treated with occlusal splints and rehabilitated with dental prosthesis. Material and methods: Sixty volunteers, both genders, aging from 20 to 65 years, diagnosed with TMD, were randomly selected within the university's patient databank. The volunteers were divided into two groups: G1 - 30 males and G2 - 30 females. The volunteers underwent a standard clinical evaluation for TMD diagnosis. Psychological evaluations were performed through Goldberg's General Health Questionnaire (GHQ), before and after 24 months of treatment. TMD treatment comprised occlusal splints and rehabilitated with dental prosthesis. The results were evaluated by Mantel-Haezel, Wilcoxon and Mann-Whitney statistical tests. Results: According to the criteria established by GHQ, the interpretation of the symptom scores should be applied based on gender, because the scores have different values for male and female, consequently no comparisons were made between the groups. There were significant statistical difference in G2 when the variables psychic stress (p = 0.002) and psychosomatic disorders (p = 0.007) were observed.In G1, the variables for psychosomatic disorders (p = 0.002) and general health (p = 0.021) were statistically significant. Significant differences were found in both groups for all the evaluated symptoms (p < 0.005). Conclusion: The used therapy positively interfered in the remission of symptoms and in the incidence of minor psychic disorders of TMD patients.

Keywords: temporomandibular joint dysfunction syndrome; occlusal splints; oral rehabilitation.

Introduction

Temporomandibular disorder (TMD) is a pathology whose signs and symptoms are associated with pain and functional/structural disturbs of the stomatognathic system, especially those related to the temporomandibular joints (TMJ) and masticatory muscles 17,20,30.

Currently, the multifactorial etiology of TMD is a literature consensus 1. However, several controversies have existed regarding to the role played by the psychological components in TMD 14, mainly when it is affirmed that the emotional disturbs may cause muscle hyperactivity induced by the central nervous system, leading to parafunction, resulting in occlusal abnormalities 2.

Several studies have been conducted on the emotional features of TMD patients, mainly those considered as refractory, as well as on occlusal splint therapy, and prosthetic rehabilitation 24,30,26. The emotional factor underestimation has been hypothesized, which would justify TMD multidisciplinary diagnosis and treatment 19,22.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the evolution of both TMD signs and symptoms and non-psychotic psychiatric disturbs in TMD patients, treated with occlusal splints and posteriorly rehabilitated with dental prosthesis.

Material and methods

This study project was approved by the Ethical Committee in Research of the School of Dentistry of Piracicaba, University of Campinas, under protocol number #157/2004. All participants signed a free and clarified consent form to agree in participating of the study.

Sixty volunteers, both genders aging from 20 to 65 years, diagnosed with TMD and needing prosthetic rehabilitation were selected. The patients were registered in the Center of Study and Treatment of the Functional Alterations of the Stomatognathic System, School of Dentistry of Piracicaba, State University of Campinas. The participants were randomly divided into two groups: G1 – n = 30 males; G2 – n = 30 females. Both groups were initially treated with occlusal splints and then prosthetically rehabilitated. TMD diagnosis was performed through anamnesis and clinical and radiographic (panoramic radiograph) examination of TMJs, according to the university center protocol 7,12,13,20,28,31. These have also been used for searching articular and muscular signs and symptomatology associated with neurophysiologic conditions, which are related to systemic and/or postural alterations 12,13. In this study, the following symptoms were considered: articular symptoms – presence of clicking, popping or grating sounds, catching or locking of the joint during the mandible's movements, limitations in opening or closing the mouth, condilar displacement during mastication, numbness, tinnitus, and articular pain while chewing; muscular symptoms: face tiredness by waking, tiredness during mastication, pain in temporal muscle area and insertion, pain in masseter muscle area, pain in frontal muscle area, pain and unspecific symptoms in the nape, neck and back, visual clouding, dizziness, numbness, itching or discharge sensation in the ears. Pain symptomatology assessment was executed through visual analogue scale 30, in which the volunteers indicated their impression regarding to the pain occurrence and intensity.

All volunteers were oriented to fill in Goldberg's General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) 21, according to their current status. Goldberg's General Health Questionnaire is a self-administered questionnaire with 60 items on non-psychotic psychiatric symptoms. The phases of the questionnaire application, volunteer training for the questionnaire filling, and results' calculation by the examiners were supervised by a psychologist.

GHQ is divided into six factors: psychic stress (PS), death wish (DW), distrust of the person's own performance (DP), sleep disorders (SD), psychosomatic disorders (PD), and general health (GH). The response scores were based on Likert's system 4-point scale 7: absolutely not (1), not more than usual (2), a little more than usual (3), much more than usual (4). Questionnaires with more than 10% of unanswered questions were discarded; questionnaires with less than 10% of unanswered questions were accepted, but the blank questions were subtracted from the score calculation.

Because several factors showed a different number of questions, it was not possible to compare the raw that is, the sum of the response's scores of each factor divided by the number of questions 29.

According to GHQ criteria, the symptom scores interpretation should be applied based on gender, because the scores have different values for male and female 3, since this study's population was non-psychotic. Symptom scores equal or greater than 3 indicates the presence of disturbs; cases close to this number should be considered as borderlines 3.

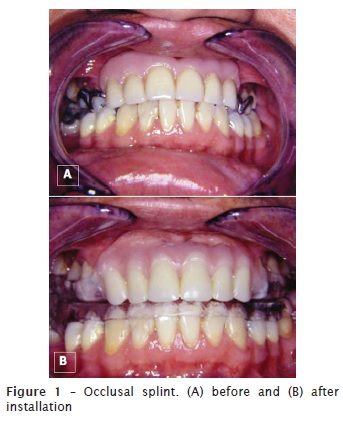

In both groups, after the filling in of both the clinical records and GHQ, the volunteers were referred to the Course of Specialization in Dental Prosthesis, School of Dentistry of Piracicaba, State University of Campinas. Treatment was executed in two phases: the first phase comprised the use of occlusal splints 11,12,19,27,30 for a period of 120 days with following-up appointments at every 2 weeks, aiming to the functional equalization of the muscles and the remission of the pain symptomatology (figure 1); the second phase comprised the rehabilitation of the prosthetic tooth spaces, according to each case indication. At this second stage, two volunteers of each gender were discarded because they were not interested in continuing to participate in the study. After 24 months, the volunteers of both groups were reassessed.

Data were evaluated by Mantel-Haenzel and non parametric Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney tests, with level of significance set at 5%.

Results

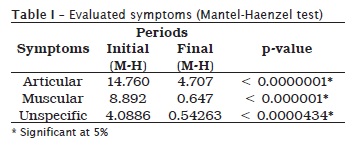

For all articular (p < 0.0001 – table I), muscular (p < 0.0001 – table I), and unspecific symptoms associated with neurophysiologic conditions (p < 0.001 – table I), the obtained results revealed that when all symptoms were evaluated together, G1 and G2 showed statistically significant differences before and after treatment.

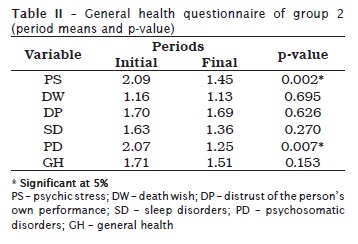

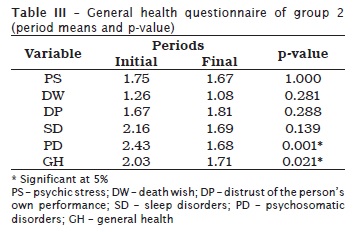

GHQ results exhibited that for G2 there was a significant difference before and after treatment for the variables psychic stress (p = 0.002 – table II) and psychosomatic disturbs (p = 0.007 – table II). For G1, the differences were statistically significant for the variables psychosomatic disturbs and general health (p = 0.021 – table III).

Discussion

Several researchers have demonstrated special interest in studying the incidence of temporomandibular disorder signs and symptoms, as well as the role of the psychological factors in these disorders. Previous studies have suggested a multifactorial etiology, which provided important information not only on the masticatory system integrity, but also on the treatment necessity.

Occlusal splint therapy promoted clinical response change, similarly to the studies of et al. 28 and Ekberg et al. 3. The neurophysiologic adequacy obtained with the occlusal splint followed by the prosthetic rehabilitation was effective for the remission of TMD patients' signs and symptoms. The initial therapy with occlusal splints has been longer considered an effective therapeutic modality for TMD signs and symptoms remission 24. Although the prevalence of the initial signs and symptoms by age-group was not considered as a variable in this study, we found a prevalence of 33.33%, with the most prevalent age-group from 31-40 years for both groups.

The psychological factors may act in the perpetuation of the initial TMD signs and symptoms 19,22; however, literature has presented controversies regarding the real role of these events 14. For this purpose, several psychological tests can be used to standardize the researches, allowing the results' comparison and the obtainment of a TMD psychological profile 30,26,16,4. On one hand, there were no ways of identifying groups or subgroups more predisposed to this pathology. On the other hand, there is a literature tendency towards the formation of TMD psycho-behavioral features, because the patients could show high levels of anxiety, depression and stress 8. Marbach 15 suggested that personality features do not exist to differentiate TMD from non-TMD patients.

The results of this study exhibited a statistical significant difference for the variables psychic stress and psychosomatic disturbs in the female group and psychosomatic disturbs and general health in the male group. Jaspers et al. 8, by applying GHQ in TMD patients, found higher rates for the variable stress; however, this did not interfere with the patients daily routine. Since a tendency towards stress increase occurred, certainly the non significance in modifying the patient's routine should be credited to the small number of patients in these authors' study. Manfredini et al. 14 affirmed that the psychological factors have not been well defined as either predisponent or perpetuating factors. Therefore, TMD should be treated both under the physical and psychological aspect to assure treatment success. Pereira et al. 21 reported that the psychological and gender variables are important factors indicative of the risk related to TMD incidence in teenagers. Despite of these considerations, we believed that this study's treatment was effective in the remission of the symptomatology and in the reduction of the values registered for the aforementioned variables. However, further studies are necessary to evaluate the effective role of the psychological factors on TMD.

In addition to GHQ, other questionnaires have been used to evaluate TMD psychological factors. Reich et al. 22 suggested the use of DSM-II for chronic disorders as TMD because this is the official system used by the American Society of Psychiatrics. Gale e Dixon 6 employed seven questionnaires for depression and anxiety and found a correlation among depression, anxiety and TMD, suggesting the inclusion of psychological questions to evaluate the incidence of the psychological aspects on TMD. This correlation was also verified by Pereira et al. 21 using RDC axis I and II for TMD evaluation in teenagers. Meldolesi et al. 17, using the Minnesotta Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) and Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HARS), verified that TMD patients presented higher scores of psychological problems related to hysteria, hypochondria, and depression than patients without these variables; and also higher scores of anxiety than psychiatric patients. Bonjardim et al. 1 using the Hospital Anxiety and depression Scale (HADS) highlighted the statistical correlation between TMD and anxiety, but not related to depression. The results of this present study corroborate those finding in literature, with little differences regarding to the methodology and sample size 8. In our study, we opted to use GHQ because it is of simple application, high specificity and sensibility with low rate of false negative, in addition to be capable of evaluating several variables within one single questionnaire 26.

Due to TDM multifactorial etiology, Okino et al 18 verified that after the evaluation of the psychological treatment need, better results were obtained when the dentist together with the psychologist treated the patient 9. Because this present study was conducted in a way that its phases (questionnaire application, volunteers' training for filling in the questions, and results' assessment by the researches) were supervised by a psychologist, the outcomes not only enabled the differential diagnosis but also allowed the patient's referral to the specialist. This indicates that the dentist needs knowledge and training for using either GHQ or other questionnaire in addition to the knowledge of the specific clinical TDM protocol to perform the differential diagnosis and multidisciplinary treatment, as shown by Kiney et al. 9. These authors reported that the etiology is a perpetuating factor of TMD and that the dentist must be aware of the patient's psychological conditions to avoid failures, such as refractory treatment cases. Wright & Schiffmam 29 alerted to the use of a biopsychosocial model (physical, psychological and environmental evaluation) in the determination of each etiologic factor of TMD, therefore establishing it primary cause and how much each factor contributed to it, instituting the best therapy which can include mandibular exercises (physiotherapy), relaxation, acupuncture, and stress management.

The emotional factor is important for TMD development 1,22 and there is the need of its evaluation to institute the best therapy based on a coherent and accurate diagnosis, and on solid scientific basis. Even after the treatment, episodes of reagudization may occur, which does not exactly mean that the initial diagnosis and treatment has not been valid; the patients are interacting with the environment and their own emotions, leading to pain episodes again 8. Manfredini et al. 14 supported the existence of a close association between pain and psychosocial involvement in TMD patients and suggested that psychological suffering can be independent of the pain location; therefore, further studies would be necessary to correlate miofascial pain and TMJ pain.

Although the psychological aspects 2,19,30 may be part of the bruxism, orofacial pains, occlusal anatomy destruction and dental trauma etiology which together or separately are variables present in TMD, it is not exactly known how much these variables can cause the problem that after installation has its own path, regardless of the treatment and the healing of the psychological aspects. We clearly consider that further studies are necessary to relate the several psychological aspects to several TMD stages.

Conclusion

• The used therapy positively interfered in the incidence of articular, muscular and unspecified symptom manifestations in TMD patients;

• G2 exhibited statistically significant differences for the variables psychic stress and psychosomatic disturbs; G1 showed expressive differences for the variables psychic stress and general health.

• Root canal's apical third presented the greatest amount of filling material remnant, regardless of the used operative technique.

References

1. Bonjardim LR, Lopes-Filho RJ, Amado G, Albuquerque Jr. RLC, Gonçalves SRJ. Association between symptoms of temporomandibular disorders and gender, morphological occlusion and psychological factors in a group of university students. Indian J Dent Res. 2009;20(2):190-4. [ Links ]

2. De Boever JA, Carlsson GE, Klineberg IJ. Need for occlusal therapy and prosthodontic treatment in the management of temporomandibular disorders. Part I. Occlusal interferences and occlusal adjustment. J Oral Rehabil. 2000;27(5):367-79.

3. Ekberg E, Vallon D, Nilmer M. The efficacy of appliance therapy in patients with temporomandibular disorders of mainly myogenous origin. A randomized, controlled, short-term trial. J Orofac Pain. 2003;17(2):133-9.

4. Ekkelund SI, Husby G, Mellgren SI. Quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis – a case control study in patients living in northern Norway. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1995;13(4):471-5.

5. Feyer AM, Herbison P, Williamson AM, Silva I, Mandryk J, Hendrie L et al. The role of physical and psychological factors in occupational low back pain: a prospective cohort study. Occup Environ Med. 2000;57(2):116-20.

6. Gale EM, Dixon DC. A simplified psychologic questionnaire as a treatment planning aid for patients with temporomandibular joint disorders. J Prosthet Dent. 1989;61(2):235-8.

7. Goldberg DP. The detection of psychiatric illness by questionnaire: a technique for the identification and assessment of non-psychotic psychiatric illness. London: Oxford University Press; 1972.

8. Jaspers JPC, Heuvel F, Stegenga B, De Bont LGM. Strategies for coping with pain and psychological distress associated with temporomandibular-joint osteoarthrosis and internal derangement. Clin J Pain.1993;9(2):94-103.

9. Kinney RK, Gatchel RJ, Ellis E, Holt C. Major psychological disorders in chronic TMD patients: implications for successful management. J Am Dent Assoc. 1992;123(10):49-54.

10. Klasser GD, Greene CS. Oral appliances in the management of temporomandibular disorders. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107:212-23.

11. Landulpho AB, Silva WAB, Silva FA, Vitti M. Electromyographic evaluations f masseter and anterior temporalis muscles in patients with temporomandibular disorders following interocclusal appliance treatment. J Oral Rehabil. 2004;31(1):95-8.

12. Landulpho AB, Silva WAB, Silva FA, Vitti M. The effect of occlusal splints on the treatment of temporomandibular disorders: computerized electromyographic study. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 2002;42(3):187-91.

13. Manfredini D, Landi N, Bandettini Di Poggio A, Dellosso L, Bosco M. A critical review on the importance of psychological factors in temporomandibular disorders. Minerva Stomatol. 2003;52(6):321-30.

14. Manfredini D, Marini M, Pavan C, Pavan L, Guarda-Nardini L. Psychosocial profiles of painful TMD patients. J Oral Reabil. 2009;36:193-8.

15. Marbach JJ. The temporomandibular pain dysfunction syndrome personality: fact or fiction? J Oral Rehabil. 1992;19(3):545-60.

16. McNeill C. management of temporomandibular disorders: concepts and controversies. J Prosthet Dent. 1997;77(5):510-22.

17. Meldolesi GN, Picardi A, Accivile E, Di Francia RT, Biondi M. Personality and psychopathology in patients with temporomandibular joint pain-dysfunction syndrome – a controlled investigation. Psychother Psychosom. 2000;69(6):322-8.

18. Okino MCNH, Gallo MA, Finkelstein L, Cury FN, Jacob LS. Psicologia e Odontologia – atendimento a pacientes portadores de disfunção da articulação temporomandibular (ATM). Rev Inst Ciênc Saúde. 1990;6(2):27-9.

19. Paixão F, Silva WAB, Silva FA, Ramos GG, Cruz MVJ. Evaluation of the reproducibility of two techniques used to determine and record centric relation in Angle's class I patients. J Appl Oral Sci. 2007;15(4):275-9.

20. Pasquali L. Questionário de saúde geral de Goldberg (QSG): adaptação brasileira. São Paulo: Casa do Psicológo; 1996.

21. Pereira LJ, Pereira-Cenci T, Pereira SM, Del Bel Cury AA, Ambrosano GMB, Pereira AC et al. Psychological factors and the incidence of temporomandibular disorders in early adolescence. Braz Oral Res. 2009;23(2):155-60.

22. Reich J, Rosenblatt RM, Tupin J. DSM-III: a new nomenclature of classifying patients with chronic pain. Pain. 1983;16(4):1-6.

23. Rugh JD, Woods BJ, Dahlstrom L. Temporomandibular disorders: assessment of psychological factors. Adv Dent Res. 1993;7(2):127-36.

24. Silva FA, Silva WAB. Reposicionamento mandibular. Contribuição técnica através de férulas oclusais duplas com puas. Rev Assoc Paul Cir Dent. 1990;44(5):283-6.

25. Suvinen TI. Temporomandibular disorders part II. A comparison of psychologic profiles in Australian and Finnish patients. J Orofac Pain. 1997;11(2):147-57.

26. Tarnopolsky A, Hand DJ, Mclean EK, Roberts H, Wiggins RD. Validity and uses of a Screening Questionnaire (GHQ) in the community. Br J Psychiat. 1979;134:508-15.

27. Vedana L, Landulpho AB, Silva WAB, Silva FA. Electromyographic evaluation during masticatory function, in patients with temporomandibular disorders following interocclusal appliance treatment. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 2010,50(1):33-8.

28. Wahlund K, List T, Larsson B. Treatment of temporomandibular disorders among adolescents: a comparison between occlusal appliance, relaxation training, and brief information. Acta Odontol Scand. 2003;61(4):203-11.

29. Wright EF, Schiffmam EL. Treatment alternatives for patience with masticatory myofascial pain. J Am Dent Assoc. 1995;126(7):1030-9.

30. Zanatta G, Buarque e Silva WA, Andrade e Silva F, Ramos GG, Casselli H. Assessment of painful symptomatology in patients with temporomandibular disorders by means of a combined experimental scale. Braz J Oral Sci. 2006;5(19):1244-8.

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Wilkens Aurélio Buarque e Silva

Faculdade de Odontologia de Piracicaba, Departamento de Prótese e Periodontia

Avenida Limeira, n.º 901 – Vila Areião

CEP 13414-018 – Piracicaba – SP – Brasil

E-mail: wilkens@fop.unicamp.br

Received for publication: March 29, 2011

Accepted for publication: August 9, 2011