Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

RSBO (Online)

versão On-line ISSN 1984-5685

RSBO (Online) vol.9 no.2 Joinville Abr./Jun. 2012

Original Research Article

Tobacco cessation: what role can dental professionals play?

Abhishek Mehta I; Gurkiran Kaur II

I Associate Professor and Head, Dept. of Public Health Dentistry, Dr.H.S.Judge Institute of Dental Sciences and Hospital, Panjab University – Chandigarh (U.T.).

II School of Dentistry, University of Itajai Valley – Itajai – SC – Brazil.

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Tobacco dependence is classified as a disease by the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10), but, medical and dental professionals have neither seriously taken this fact nor made any serious attempt to tackle this disease. Apart from supporting wider tobacco control measures, oral health professionals can help patients to stop using tobacco. This may be the single most important service dentists can provide for their patients overall health. Objective:This review is prepared with the object to help both clinicians and oral health professionals to scale up their involvement in tobacco control activities, including advocacy and smoking cessation programs. Literature review:Studies have shown that 70% smokers indicate that they want to quit, but a meagre 2% succeed. The dental practice setting provides a unique opportunity to assist tobacco users in achieving tobacco abstinence. Still, More than 40% of dentists do not routinely ask about tobacco use and 60% do not routinely advise tobacco users to quit, while 61.5% of dentists believe their patients do not expect tobacco cessation services. Conclusion: Interventions by dentist has been found to be effective in helping people to quit tobacco consumption. A step-wise approach and patience must be adopted while dealing with such patients.

Keywords: tobacco cessation; dental professional; nicotine replacement therapy; oral medicine; smoking cessation.

Introduction

Currently, there are an estimated 1.3 billion smokers in the world. The total global prevalence in smoking is 29% (47.5% of men and 10.3% of women over 15 years of age smoke). Of the 1.3 billion smokers, more than 900 million live in developing countries out of which 120 million are there in India 1. Tobacco is the second major cause of death in the world. It is currently responsible for the death of one in ten adults worldwide. Every 6.5 seconds one tobacco user dies from a tobacco-related disease somewhere in the world. Cigarettes kill half of all lifetime users and half of those die in middle age (35-69 years), losing an average of 20 to 25 years of life . With current smoking patterns, approximately 500 million people alive today will eventually be killed by tobacco use. By 2030, tobacco is expected to be the single biggest cause of death worldwide, accounting for about 10 million deaths per year 4.

As research on the effects of tobacco on health continues and the number of affected people increases, the list of conditions caused by tobacco has expanded. There is nowadays evidence that almost every organ in the body is affected by tobacco consumption and now it also includes cataracts, pneumonia, acute myeloid leukemia, abdominal aortic aneurysm, stomach cancer, pancreatic cancer, cervical cancer, kidney cancer, and periodontitis. These diseases add on to the already known such as lung, oesophagus, larynx, mouth and throat cancer, chronic pulmonary and cardiovascular diseases, as well as negative effects on the reproductive system and sudden infant death syndrome. All these diseases are preventable by removing one single risk factor i.e. tobacco use. Therefore it is imperative that health care professionals including dentists must help their patient who are addicted to this habit and want to quit. This review is prepared with the objective to help clinicians and oral health professional to understand in a step-wise approach, how they can help their individual patients as well as general populations to quit habit of tobacco consumption.

Literature review

Tobacco cessation and dentists role

The dental team has a major role to play in smoking prevention. Evidence suggests that smoking cessation interventions are effective 2,7. A brief intervention will often result in significant health gain and, in the long term, reduces smoking-related health-care costs to countries. Unfortunately, advice on quitting tobacco is still neither a routine part of clinical practice for many oral health professionals nor are many National Dental Associations (NDAs) involved in tobacco control.

To implement a tobacco cessation program, clinicians should systematically identify all tobacco users at every visit. A system needs to be implemented in the clinic which ensures that tobacco use status is obtained and recorded at each patient visit. This may be carried out by the clinician or an assistant who may be trained accordingly. The forms of tobacco use such as cigarettes/beedis/gutkha, frequency and duration of use can be mentioned 9.

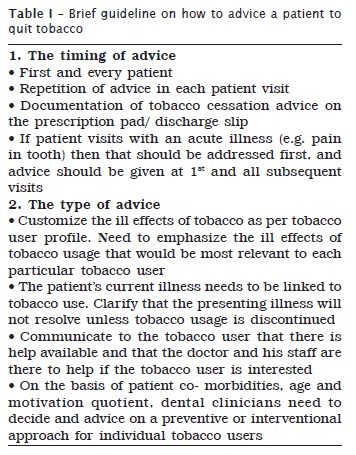

Current evidence suggests that even brief advice leads to an absolute increase in the cessation rate of about 2.5%. This indicates that for every 40 patients who receive brief advice, one will quit smoking permanently. Given the high prevalence tobacco consumption and that 70% see a clinician or a dentist at least once a year, interventions with patients who are tobacco users, can have an enormous impact 7. As a dentist, one has the unique opportunity to link the patients presenting illness to his/her tobacco use, and then prescribe tobacco cessation therapy. Table I 15 depicts a brief guideline on how to advice a patient to quit tobacco.

Next step will be to assess patients readiness to quit tobacco; it is recommended that every tobacco users readiness to make a quick attempt should be checked at each visit no matter what the presenting complaint is. Readiness may be ascertained in two ways:

1. Self assessment by patient

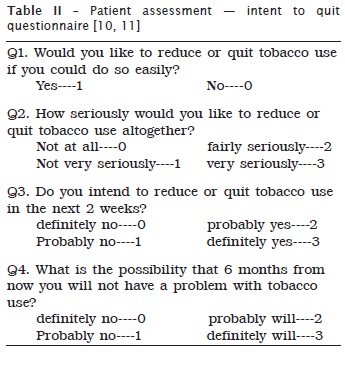

These questionnaires can be left in the waiting room or administered by nursing or secretarial staff (table II). While all patients may not be able to fill this questionnaire accurately but when it is used along with the dentist own judgment, it will definitely enhance the assessment of patients readiness to quit tobacco use.

2. Assessment by the clinician/dentist

This can be carried out by the clinician on a simple assessment of the patients body language, eye contact etc. this can be done on a simple three-point scale initially- not ready / unsure/ ready to quit 14. For those tobacco users who are not ready to quit, an attempt should be made to motivate them by giving them clear, strong, personalized advice. Building motivation is an important element in moving tobacco users from one stage to the next. Like treatment, strategies to build motivation need to be individualized. Motivation can be built by using a combination of one or more of the following techniques:

Linking the present illness to tobacco use, when possible; Illustrating the other ill-effects of tobacco use and the positives of quitting;

Creating awareness on the availability of medicines to aid in tobacco cessation;

Using successful ex-tobacco users to motivate new patients;

Emphasizing and /or demonstrating that tobacco use is an addiction and not a personal choice or life style.

However, if a tobacco user is not feeling fully motivated to quit and instead chooses to reduce the number of cigarettes/bidis/gutkha packets then the clinician should utilize this period to reinforce motivation and eventually drive complete tobacco cessation. This can be done by analyzing the reasons not to quit and addressing them appropriately. As a last resort a clinician may use a strategy called paradoxical intentional to motivate the tobacco user. Under this strategy, the clinician should ask the tobacco user to choose between continuing to take numerous medications for the primary illness or quitting tobacco use. This strategy has been found to be effective in day to day practice.

If there are tobacco users who insist that this is a matter of personal choice and they can give up whenever they decide to, a clinician can demonstrate to them that tobacco use is an addiction. Request the user to give up tobacco use for just one day and if they find it difficult, they can come back to the clinician for help. In addition to clinicians individual efforts with tobacco users, they can be also motivated by displaying educational posters in the clinic and distributing educational material in the form of newsletters, booklets, audio-visual aids and leaflets.

For tobacco users who express willingness to try and quit, help set a quit date approximately two weeks away. A day personally significant to the tobacco user makes it more relevant e.g. birthday, anniversary etc. The tobacco user should be encouraged to announce his/her decision to family members, friends and colleagues so as to mobilize their support as well as induce accountability. It is strongly recommended that the tobacco user give up completely in one go on the quit date.

Pharmaco-therapeutic interventions

Dental clinicians need to offer the option of pharmacotherapy to all patients initiating a quit attempt. FDA approved medicines includes: Varenicline, Bupropion and Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT). These medications have been found to be safe and effective for the tobacco dependent, except in the presence of contraindications or with specific populations for whom there is insufficient evidence of effectiveness (e.g. pregnant woman and adolescents). These first line medications have an established empirical record of effectiveness, and clinicians should consider these agents first in choosing a medication.

1. Bupropion 3

Bupropion was approved for smoking cessation by the US FDA in 1997. Its possible mechanisms of action include blockade of neural re-uptake of dopamine and norepinephrine, and blockade of nicotinic acetylcholinergic receptors. It is contraindicated in patients with a seizure disorder, a current or prior diagnosis of bulimia or anorexia nervosa, use of monoamine oxide (MAO) inhibitor within the previous 14 days, or in patients taking another medication that contains Bupropion. Recommended dosage for Bupropion is150 mg twice daily.

2. Varenicline 10

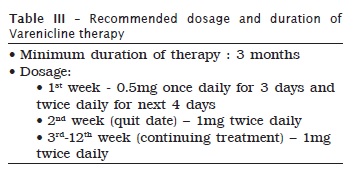

It is clinically proven to be most effective smoking cessation treatment and patients should be encouraged to use it. Varenicline is a non-nicotine medication that was approved for smoking cessation by US FDA in 2006. It is partial agonist at a4ß2 receptors designed to provide relief from craving and withdrawal (negative reinforcement), as well as diminish reward from smoking (positive reinforcement). Varenicline has produced significantly higher quit rates than Bupropion and NRT in multiple randomised controlled trials. It is well tolerated, with nausea being the most commonly seen adverse event. To avoid nausea, it should be taken with a glass of water after food. Caution is advised during its use in patients with a history of neuropsychosis disorder, though a recent cohort study in UK reported it to be safe and efficacious in such patients. Recommended dosage and duration of varenicline are shown in table III.

3. Nicotine replacement therapies (NRTs) 3

Nicotine replacement therapy medications deliver nicotine with the intent to replace, at least partially, the nicotine obtained from cigarettes or other forms of tobacco and to reduce the severity of nicotine withdrawal. NRT dosage is calibrated on the basis level of tobacco dependence. The level of tobacco dependency can be checked by asking patient to fill a simple six question closed- ended questionnaire 5. Forms of NRT currently available:

a) Nicotine gum (2 mg or 4 mg/OTC)

The gum should be chewed slightly until a peppery/mint flavor is tasted then parked in the vestibule with the cycle repeated in approximately 30 minutes. If the gum is chewed too rapidly, the patient may feel ill due to the rapid release of nicotine into the system. In addition acidic beverages may interfere with the absorption of nicotine. Patients with dentures or temporomandibular joint problems have reported difficulties chewing the gum and may benefit from the NRT lozenge.

b) Nicotine Transdermal Patch (7 mg, 14mg, 21 mg / OTC)

The transdermal patch is applied directly to the skin allowing nicotine to be absorbed through the skin. Up to 50% of patients experience mild skin irritation, which often clears up in a few days. Insomnia has also been reported in connection with the transdermal patch.

c) Nicotine inhaler (prescription only)

Nicotine from the nicotine inhaler is not actually inhaled. The patient takes a puff from the inhaler, holds the aerosols in the mouth and pharynx area, and then exhales. Mouth and throat irritation, coughing, and rhinitis are common though these reactions are often temporary.

d) Nicotine nasal spray (prescription only)

Nicotine nasal spray poses local irritations with 94% of users reporting moderate to severe nasal irritation initially and 81% reporting irritation after three weeks of use. In addition about 15-20% of patients report using the nicotine nasal spray longer than recommended because it is potentially addictive.

e) Nicotine lozenge (2 mg or 4 mg/OTC)

The nicotine lozenge is a new and effective nicotine replacement delivery system that seems to have addressed many of the drawbacks reported with other NRTs. When placed in the vestibule, the lozenge is able to deliver the whole dose of nicotine. Researchers found the lozenge delivered 25% to 27%7% more nicotine than the same dose of nicotine gum due to the retention of nicotine in the gum base. With the increase of available nicotine, participants found they experienced less cravings. Similar to nicotine gum, acidic beverages may interfere with the absorption of nicotine, therefore, patients should be advised to avoid coffee, juices, and soft drinks 15 minutes before they use the lozenge.

Supportive therapy, follow-up and relapse prevention

Dentist must consider supportive therapy for use on a case – by – case basis after first line medications (either alone or in combination)have been used without success or are contraindicated and he/she should consider referrals to specialist like chest physician or psychiatrist in your area for advice and intense counselling.

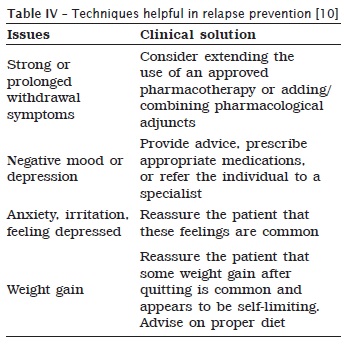

Tobacco users, who have recently quit, face a high risk of relapse. Although most relapse occurs early in quitting process, some relapse occurs months or even years after the quit date. The best strategy for producing high long term abstinence rates appears to be the use of the most effective cessation medication during the quit attempt and providing practical advice and motivation in each visit. The first prescription is advised for at least 15 days, making it a point to emphasize the total duration therapy, follow up with the patient should be. First month: weekly contact, 2nd and 3rd months: monthly and for rest of first year: quarterly. At each visit, dentist has to check for the typical issues that arise in tobacco cessation therapy and address them before they result in relapse. Examples of a few issues and how to address them are as follows (table IV).

In case the patient relapses, the clinician must identify cause of relapse (clinician and social), be accepting and empathetic towards the patient and refer the patient to suitable specialist for co-morbidity evaluation and treatment, if need is felt.

Once you are sure patient has quit tobacco habit successfully, congratulate and encourage the patient on his/her efforts, discuss coping strategies for withdrawal symptoms, urges and triggers, review use of tobacco cessation medication, if relevant and develop a specific extended follow-up plan that includes several visits or numerous phone contacts. As a part of extended follow up, clinicians need to monitor the patient for a minimum of three months. Ideally, follow-up for a year should be done 13.

Tobacco cessation at community level 6,12

Dentist can work with government and non-government organizations working for tobacco cessation in your area, he/she could:

Contribute to the formulation of national plans of action for tobacco control;

Work with other health professional organizations to develop a common position on tobacco control and consider establishing a coalition;

Use the news media and work with politicians to make them feel that it is in their interest to accept invitations to meetings and other events that focus on tobacco control issues;

Campaign for smoke-free/tobacco-free health care facilities to make nonsmoking the norm;

Influence the content of health professional education and motivate students by setting up a tobacco control body;

Carry out surveys and prepare regular reports on tobacco related issues highlighting tobacco control priorities; and

Lobby for public and private reimbursement for cessation counseling.

Conclusion

The current literature suggests that dental interventions conducted in the dental office and school community setting is more effective than usual care for promoting tobacco use cessation. The public health benefits of tobacco cessation interventions within the dental setting are potentially significant and there is an advantage of cessation interventions using dental professionals 2. Tobacco usage is going to emerge as a single most known cause of mortality and morbidity in the world, therefore, it is imperative that various health agencies and professionals must work together to help their patients and public quit this habit at the earliest.

References

1. Beaglehole RH, Benzian HM. Tobacco or oral health: an advocacy guide for oral health professionals. FDI World Dental Federation, Ferney Voltaire, France / World Dental Press, Lowestoft, UK; 2005. [ Links ]

2. Carr A, Ebbert J. Interventions for tobacco cessation in the dental setting. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; 2006. Issue 1. Art. No.: CD005084. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005084.pub2.

3. Davis JM. Tobacco cessation for the dental team: a practical guide part II: evidence-based interventions. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2005 Nov;(6)4:178-86.

4. Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ. Treating tobacco use and dependence. Clinical practice guideline. Rockville: USDHHS; 2000.

5. Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1119-27.

6. Mathews Sebastian. National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences: tobacco users a smart guide WHO India; 2007.

7. Parrott S, Godfrey C, Raw M. Guidance for commissioners on the cost-effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions. Thorax. 1998;53,Suppl 5(2):S1-S38.

8. Prabhat Jha. A nationally representative case – control study of smoking and death in India. N Engl J Med. 2008 Mar;358(11):1137-47.

9. Practice of tobacco cessation therapy – a stepwise algorithm for Indian clinicians. Tobacco Cessation Clinicians Council of India; 2010.

10. Richmond RL. Multivariate models for predicting abstention following interventions to stop smoking by general practitioners. Addiction. 1993;88:1127-35.

11. Sobell LC. Fostering self-charge among problem drinkers: a proactive community intervention. Addictive Behaviors. 1996;21(6):817-33.

12. Smoking cessation services in primary care, pharmacies, local authorities and workplaces, particularly for manual working groups, pregnant women and hard to reach communities. Nice Public Health Guidance 10. 2008 Feb.

13. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. U.S. Public Health Service Clinical Practice executive summary. 2008 PHS Guidelines Update Panel, Liaisons, and Staff. Respir Care. 2008 Sep;53(9):1217-22.

14. Wen CP. Barriers to smoking cessation: are they really insurmountable? World Med Journal. 2009;55(1).

15. West R, McNeill A, Raw M. Smoking cessation guidelines for health professionals: an update. Thorax. 2000;55:987-99.

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Dr. Abhishek Mehta

Associate Professor and Head Dept. of Public Health Dentistry, Dr. H. S.

Judge Institute of Dental Sciences and Hospital, Panjab University

Chandigarh (UT)-14

E-mail:mehta_abhishek2003@yahoo.co.in

Received for publication: June 14, 2011.

Accepted for publication: November 17, 2011.