Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

RSBO (Online)

versão On-line ISSN 1984-5685

RSBO (Online) vol.9 no.4 Joinville Out./Dez. 2012

Original Research Article

Survey on jaw fractures occurring due to domestic violence against women

Thiago Serafim Cesa I ; Regiane Benez Bixofis I ; Jean Carlos Della Giustina I ; José Luis Dissenha I ; Maria Isabela Guebur I ; Glória A. L. Huber I ; Laurindo Moacir Sassi I

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Violence against women has become a public health problem, and the dentist is the main responsible for the treatment of their victims, since numerous cases with a high incidence of impaired maxillomandibular complex occurred. Objective: The aim of this study was to analyze the prevalence and evolution of jaw fractures in woman due to domestic violence. Material and methods: The medical files from the Hospital and Maternity of São José dos Pinhais/PR (HMSJP) was searched for female patients diagnosed with jaw fractures caused by trauma, considering the aggressor and the prevalence in the period from January 2001 to May 2003. Results: There were 23 women with jaw fractures, aged from 15 to 43 years. Nasal fractures were the most prevalent, followed by the zygomatic complex and mandible fractures. The husbands were the main responsible for the attacks. The fractures treated by reduction had satisfactory bone consolidation. Conclusion: Patients with jaw fractures had favorable bone consolidation after being submitted to surgical treatment. Nasal fractures were the most prevalent type and the husband was most responsible for the attacks.

Keywords: domestic violence; aggression; jaw fractures.

Introduction

Violence against women, children, adolescents, elderly, disabled and mentally people is considered a global phenomenon that goes beyond the barriers of ethnicity, culture, politics and economics and it is currently a challenge for public health in relation to the management of the human resources and organization of the services 1,17,30.

There are several approaches to determine their causes, treat their victims, inflict punishment for those responsible and, above all, prevent its recurrence 2.

The woman can be subjected to various types of intrafamiliar violence, such as psychological, physical, sexual, and negligence. This proves the failed hypothesis that the affective connections, raised in family environment, would protect its weakest members 23.

The dentist is a professional who has the most contact with the victims of personal injury, since many cases experiencing a high incidence of impairment of the maxillomandibular complex. This involves technical training for the proper treatment of facial bone and tooth fractures, and skin and mucosa lacerations, as well as the educational training to help in the combat against the domestic violence 12.

The dentist should be well oriented in relation to the ethical-legal aspects, because in cases of domestic violence this professional must have a proper conduct regarding to the identification, appropriate record and the compulsory notification of the case, to preserve the dignity, health and life of the human being 16.

The identification of the woman victim of domestic aggression is accomplished through a detailed clinical examination of the oral cavity, head and neck, which will reveal the signs of the beatings 21. The professional conduct when confronted with such a patient occurs in three steps in addition to the treatment executed: compulsory notification, confidentiality and documentary record of the lesions examined 29.

The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of the maxillomandibular fractures in women victims of domestic violence.

Material and methods

Firstly, the study project was submitted and approved by the Ethical Committee in Research of the Erasto Gaertner Hospital, Curitiba (PR, Brazil), under protocol n. 416.

A retrospective study was conducted through the assessment of the medical records of the female patients enrolled at the Hospital and Maternity of São José dos Pinhais/PR, Brazil (HMSJP). All patients evaluated were admitted during the emergency room of the hospital complaining about domestic violence and received the treatment of the aggression sequelae of the facial fractures, considering the aggressor and prevalence, from January, 2001 to May, 2003.

Results

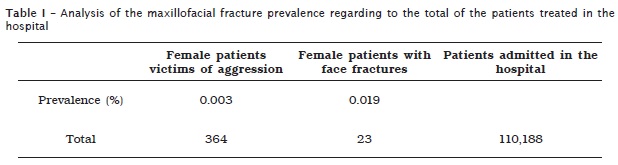

Table I shows that during the period of 29 months (from January, 2001 to May, 2003). Of the 110,188 patients admitted in the hospital, 364 were women victims of aggression; alcohol and drugs were the main factors related to the aggressions. Of this total, 23 patients exhibited maxillomandibular fracture and they were treated by the Service of Traumatology and Bucomaxillofacial Surgery. The age of these women ranged from 15 to 43 years-old.

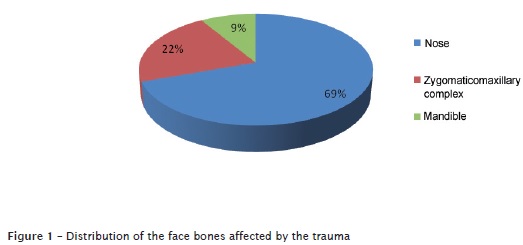

Figure 1 shows the data regarding to the most affected sites: nasal bone (69%), zygomaticomaxillary complex (22%) and mandible (9%). The nasal bone is therefore the most prevalent one among the face bones in the women victims of domestic aggression.

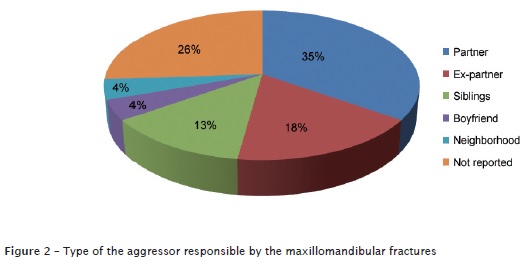

The information regarding to the aggressors are shown figure 2: the husband seems to be the most responsible for the aggressions (35%). It is highlighted that 26% of the women victims of aggression did not denounce the aggressor. Following, the ex-partners appeared in 18% of the cases, followed by the siblings (13%) and, with small percentage, the boyfriends and the neighborhood (4% each).

In 100% of the cases, the treatment was conducted through the surgical reduction of the sequelae of the aggression and the face fractures. Bone consolidation was achieved satisfactorily in all patients.

Discussion

According to some authors, such as Fonseca et al. 13, Rodriguez and Guerra 22 and Sansone et al. 24, the abuse and/or threating also causes psychological injuries, because they destroy the self-esteem of the women, leading to an increased risk of developing problems such as depression, phobias, posttraumatic stress disorder, suicidality and increased consumption of alcohol, tobacco and other drugs. This fact is confirmed by shame and fear of revealing the origin of the injury, when the woman seeks medical help.

The violence against the woman, according to Day et al. 11, is the most widespread abuse of the human rights in the world and the least recognized one, because it occurs inside the person's home, which resulted in immense individual, family and social damages. The United Nations General Assembly, in 1993, officially defined this violence modality as: "Any act of gender-based violence that results or may result in, physical, sexual, psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, either occurring in public or in private life".

Some indicators are described by Souza et al. 30 as associated with domestic violence: low socioeconomic status, low quality of social support, black race / ethnicity, youth and woman, resulting in the so-called gender violence. Alvarado-Zaldivar et al. 1 and Schraiber et al. 27 still reported that the violent reactions are facilitated by alcohol and drug abuse, history of prior violence, lack of communication and jealousy crisis. In this study, patients had low socioeconomic status, and alcohol and drugs were the main factors related to aggressions.

Casique and Furegato 9 and also Garbin et al. 15 defined it as the power relationship in which one absolutely dominates because of the annulment of others. In this context, some men fuel the belief of ownership over women, regardless of the relationship between them. Thus, the aggressors are usually current partners or former partners, or ex-boyfriends, brothers, sons and neighbors, which corroborates the findings of this study, in which eight aggressions were performed by the partners, four by ex-partners, three by siblings, and one by the boyfriend and one by the neighbor.

In case of aggression, one or more parts of the body may be injured. Schraiber et al. 28 cited that the most affected body areas are the face, neck and arms. Garbin et al. 15 showed that the preference for the face represents a humiliation that the aggressor imposes on the woman by achieving her face because the lesion becomes visible, and by depreciating her beauty, the aggressor reinforces the power in relation to the person victimized. On the other hand, the attacks on hands and arms would mean an attempt of defense by the victim. The authors also reported that the most common facial fractures occurred in the periorbital and frontal region, and teeth. The data found by this present study demonstrated the prevalence of the fractures on the most prominent regions of the face: 16 nose fractures, five zygomaticomaxillary complex fractures and two mandible fractures.

The dentist, according to Tornavoi et al. 31, may be professionally involved with the violence against women, because he/she is the professional who identifies the aggressions or treats them, since they come from some sort of physical aggression. In a research conducted by Fracon et al. 14, 68.43% of the dentists knew how to differentiate an accidental lesion from one caused by violence. Most clinicians realizing these aggressions opt to talk to these women to convince them to make a complaint against the aggressor, which makes the dentist a key part in the treatment of the victims of violence 12,15. Hsieh et al. 19 cite the AVDR standard treatment protocol, which includes: Ask, Validate, Document and Refer. This is a facilitating sequence in the appointment of these patients.

On the other hand, the bucomaxillofacial surgeons, according to Silva et al. 29, should provide a specialized treatment to solve the maxillomandibular fractures, tooth fractures, lesions in soft tissues and other situations which jeopardize the phonetics, mastication, and/or aesthetics. Sassi et al. 25 reported the satisfactory bone consolidation in mandible fractures treated by open reduction. In another study, Sassi et al. 26 evaluated 50 cases of the zygomaticomaxillary fracture, treated by open reduction, in which the aesthetic and function were reestablished satisfactorily, as well as the bone repair. Hashemi et al. 18 reported the treatment of face fractures due to domestic. The open reduction was chosen for the fractures of the mandible and of the zygomatic bone; in the nose fractures, the techniques used were the close reduction. In this present study, the surgical reduction was employed to treat the sequelae and the face fractures due to the domestic violence aggressions against the victims, resulting in a satisfactory bone consolidation.

The Brazilian Law n. 10.778/2003 7 establishes the compulsory notification in the cases of the violence against the women who would be treated in the public and private health services. In the dental office, according to the Decree n. 5.099/2004 5, which regulates the Law n. 10.778/2003 7, the notification should be performed by the dentist, confidentially, by using the ICD-10 (T74 and others) in a specific form produced by the Brazilian Information System for Notifiable Diseases 8 to be referred to either the reference service or the competent health authority. From an ethical point of view, the notification means the fulfillment of the fundamental obligation of the dentist, regarding to the zeal for the health and dignity of the patient, according to which establishes the item V of the article 5th of the Brazilian Dentistry Code of Ethics 3. It is the obligation of the dentist, according to the item II of the article 66 of the Brazilian Criminal Code, of notifying the cases in which are observed lesions of the physical nature and which can be criminally classified as serious or very serious 4, likely to the minor injuries, according to the article 41 of the Maria da Penha Law. Concerning to children and adolescents, the article 245 of the Brazilian Statute of Children and Adolescents obliges the dentist to inform situations of child abuse. If the dentist does not notify, he/she will be penalized through a fine raging from three to 20 reference wages, which can be doubled if there is recurrence 6.

According to Garbin et al. 16, in cases of the aggression involving the neck and head, the forensic police also acts performing examinations and reports that should be preferentially executed by a dent ist to prevent errors in the dental descriptions, The rich details together with the integrity of the information collected and of the examinations carried out during the appointments collaborate to the Justice can ensure the execution of the laws of protection against violence.

Deslandes et al. 12 explained that the reception in emergency rooms is fundamental to prevent the relapse of domestic violence. The emergency services must provide a specific surgical and clinical quality treatment through orthopedists, dentists, ophthalmologists, surgeons and clinicians, but may not be limited to those procedures. This was confirmed by Fonseca et al. 13 and Nelms et al. 20, who stated that health professionals should be encouraged and capacitated to notify and / or mobilize other professionals and services for monitoring these women, and to discuss what leads to the underreporting of such cases. The training of the students during the graduation would lead to the right conduct in such situations.

Conclusion

Considering the data found in this study, it can be concluded that:

• The treatment of the injury sequelae and facial fractures occurred through surgical reduction with satisfactory bone healing;

• The nose fractures were the most prevalent;

• The partner was the most responsible for the aggressions.

References

1. Alvarado-Zaldivar G, Salvador-Moysén J, Estrada-Mart ínez S, Terrones-Gonzál iz A. Prevalência de violencia doméstica en la ciudad de Durango. Salud Pública Méx. 1998;40(6):481-6. [ Links ]

2. Audi CAF, Segall-Corrêa AM, Santiago SM, Andrade MGG, Pérez-Escamilla R. Violência doméstica na gravidez: prevalência e fatores associados. Rev Saúde Pública. 2008;42(5):877-85.

3. Brasil. Conselho Federal de Odontologia. Resolução n.º 42, de 20 de maio de 2003. Aprova o Código de Ética Odontológica. Rio de Janeiro; 2003.

4. Brasil. Decreto-Lei n.º 3.688, de 3 de outubro de 1941. Lei das Contravenções Penais. Rio de Janeiro; 1941.

5. Brasil. Decreto n.º 5.099, de 3 de junho de 2004. Regulamenta a Lei n.º 10.778, de 24 de novembro de 2003, e institui os serviços de referência sentinela. Brasília; 2004.

6. Brasil. Estatuto da Criança e do Adolescente. Brasília; 1990 [cited 2006 Nov 6]. Available from: URL:http://www.amperj.org.br/store/legislacao/ codigos/eca_L8069.pdf.

7. Brasil. Lei n.º 10.778, de 24 de novembro de 2003. Estabelece a notificação compulsória, no território nacional, do caso de violência contra a mulher que for atendida em serviços de saúde públicos ou privados. Brasília; 2003.

8. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Instrução Normativa n.º 2, de 22 de novembro de 2005. Regulamenta as atividades da vigilância epidemiológica com relação à coleta, ao fluxo e à periodicidade de envio de dados da notificação compulsória de doenças por meio do Sistema de Informação de Agravos de Notificação (Sinan). Brasília; 2005.

9. Casique CL, Furegato ARF. Violência contra a mulher: reflexões teóricas. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem. 2006;14(6):950-6.

10. Castro R, Peek-Asa C, Ruiz A. Violence against women in Mexico: a study of abuse before and during pregnancy. Am J Public Health. 2003 Jul;93(7):1110-6.

11. Day VP, Telles LEB, Zoratto PH, Azambuja MRF, Machado DA, Silveira MB et al. Violência doméstica e suas diferentes manifestações. Rev Psiquiatr Rio Gd Sul. 2003;25(1):9-21.

12. Deslandes SF, Gomes R, Silva CMFP. Caracterização dos casos de violência doméstica contra a mulher atendidos em dois hospitais públicos do Rio de Janeiro. Cad Saúde Pública. 2000;16(1):129-37.

13. Fonseca RMGS, Leal AERB, Skubs T, Guedes RN, Egry EY. Violencia doméstica contra la mujer en la visión del agente comunitario de salud. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem. 2009;17(6):974-80.

14. Fracon ET, Silva RHA, Bregagnolo JC. Avaliação da conduta do cirurgião-dentista ante a violência doméstica contra crianças e adolescentes no município de Cravinhos (SP). RSBO. 2011 Jun;8(2):153-9.

15. Garbin CAS, Garbin AJI, Dossi AP, Dossi MO. Violência doméstica: análise das lesões em mulheres. Cad Saúde Pública. 2006;22(12):2567-73.

16. Garbin CAS, Rovida TAS, Garbin AJI, Saliba O, Dossi AP. A importância da descrição de lesões odontológicas nos laudos médico-legais. Rev Pós- Grad. 2008;15(1):59-64.

17. Guedes MEF, Moreira ACG. Gênero, saúde e adolescência: uma reflexão a partir do trabalho com a violência doméstica e sexual. Mudanças – Psicologia da Saúde. 2009;17(2):79-91.

18. Hashemi HM, Beshkar M. The prevalence of maxillofacial fractures due to domestic violence – a retrospective study in a hospital in Tehran, Iran. Dental Traumatology. 2011;27(5):385-8.

19. Hsieh NK, Herzig K, Gansky SA, Danley D, Gerbert B. Changing dentists' knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors regarding domestic violence through an interactive multimedia tutorial. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137(5):596-603.

20. Nelms AP, Gutmann ME, Solomon ES, Dewald JP, Campbell PR. What victims of domestic violence need from the dental profession. J Dent Educ. 2009;73(4):490-8.

21. Ochs HA, Neuenschwander MC, Dodson TB. Are head, neck, and facial injuries markers for domestic violence? J Am Dent Assoc. 1996;127(6):757-61.

22. Rodriguez JCR, Guerra MCP. Mujeres de Guadalajara y violencia doméstica: resultados de un estudio pi loto. Cad Saúde Públ ica. 1996;12(3):405-9.

23. Roque EMST, Ferriani MGC. Desvendando a violência doméstica contra crianças e adolescentes sob a ótica dos operadores do direito na comarca de Jardinópolis – SP. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem. 2002;10(3):334-44.

24. Sansone RA, Reddington A, Sky K, Wiederman MW. Borderline personality symptomatology and history of domestic violence among women in an internal medicine setting. Violence Vict. 2007;22(1):120-6.

25. Sassi LM, Dissenha JL, Guebur MI, Bezeruska C, Hepp V, Radaelli RL et al. Fraturas da mandíbula: revisão de 82 casos. Rev Bras Cir Cabeça Pescoço. 2010;39(3):190-2.

26. Sassi LM, Dissenha JL, Guebur MI, Bezeruska C, Hepp V, Radaelli RL et al. Fraturas de zigomático: revisão de 50 casos. Rev Bras Cir Cabeça Pescoço. 2009;38(4):246-7.

27. Schraiber LB, d'Oliveira AFPL, Couto MT. Violência e saúde: estudos científicos recentes. Rev Saúde Pública. 2006;40:112-20.

28. Schraiber LB, d'Oliveira AFPL, França-Junior I, Pinho AA. Violência contra a mulher: estudo em uma unidade de atenção primária à saúde. Rev Saúde Pública. 2002;36(4):470-7.

29. Silva RF, Prado MM, Garcia RR, Daruge Júnior E, Daruge E. Atuação profissional do cirurgiãodentista diante da Lei Maria da Penha. RSBO. 2010 Mar;7(1):110-6.

30. Souza ER, Ribeiro AP, Penna LHG, Ferreira AL, Santos NC, Tavares CMM. O tema da violência intrafamiliar na concepção dos formadores dos profissionais de saúde. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva. 2009;14(5):1709-19.

31. Tornavoi DC, Galo R, Silva RHA. Knowledge of dentistry's professionals on domestic violence. RSBO. 2011;8(1):54-9.

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Laurindo Moacir Sassi

Rua Dr. Ovande do Amaral, n. 201 – Jardim das Américas

CEP 81520-060 – Curitiba – PR – Brasil

E-mail: sassilm@onda.com.br