Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Links relacionados

Compartilhar

RSBO (Online)

versão On-line ISSN 1984-5685

RSBO (Online) vol.13 no.2 Joinville Abr./Jun. 2016

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE

Oral diseases diagnosis rate during an oral cancer prevention campaign in Fernandópolis, Brazil, 2014

Luciana Estevam SimonatoI; Saygo TomoII; Karina Gonzales Camara FernandesI; Marlene Cabral Coimbra da CruzI; Nagib Pezati BoerI

I Dentistry School, Camilo Castelo Branco University – Fernandópolis – SP – Brazil

II Araçatuba Dental School, Universidade Estadual Paulista, Oral Oncology Center – Araçatuba – SP – Brazil

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Oral cancer is a worrying disease which claims for actions aiming its early diagnosis and prevention. Objective: To describe lesions diagnosed during oral cancer prevention campaign performed in the city of Fernandópolis, Brazil, in 2014. Material and methods: Patients who attended for the basic health units of the city of Fernandópolis on the day of the campaign were examined by a previously trained dentist who searched for oral lesions suggestive for oral squamous cell carcinoma or potentially malignant lesions. Patients with suspicious lesions were scheduled for re-evaluation by an expert in oral diseases for obtaining the right diagnosis of the lesions. Results: 1,003 patients were examined during the campaign. Among them, 94 presented oral lesions, although, only 54 attended for re-evaluation and adequate diagnosis conduct by the dentist expert in oral diseases. Of the re-evaluated patients, 42 (77.77%) were diagnosed with oral benign lesions, whereas 13 (24.07%) were diagnosed with normal oral variation and only 1 (0.09%) was diagnosed with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Conclusion: Low oral malignant lesions diagnosis rates found on this campaign might be due to lack of methodology, which needs to be improved aiming to reach patients in real risk groups for oral cancer development. Furthermore, based on the rated of benign lesions and normal oral variations, dentists need more continued education regarding oral cancer for clinically detect oral malignant lesions and instruct patients regarding this malignancy.

Keywords: oral neoplasms; oral health; public health.

Introduction

As one of the most common mal ignant neoplasms and demonstrating low cure and fiveyear survival chances, oral and oropharyngeal cancer represents a pertinent public health problem worldwide 12. With approximately 300,000 new cases diagnosed every year, the oral cavity is the 8th anatomical site mostly affected by malignant lesions 22. For the year 2014, 11,280 new cases were estimated for males, whereas 4,010 new cases were estimated for females in Brazil 9. Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), which develops from the lining epithelium, is the most common malignant lesion affecting oral mucosa, being responsible for nearby 90% of all oral malignancies 21. Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) relation with harmful habits, such as abusive alcohol drinking and tobacco smoking, is already well established, nevertheless, further factors, as solar radiation chronic exposure and human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, might also be associated to OSCC development 6,8,19,25.

Most commonly, OSCC clinical appearance consists on a painless ulcer, however might develop as exophytic lesions, or in less advanced cases, leukoplastic or erythroplastic plaques 6,21. In some cases, OSCC might develop from potentially malignant lesions, which according to the World Health Organization (WHO) are lesions with a higher potential to evolve with malignancy when compared with the normal mucosa 29. Among these lesions, leukoplakia stands out as the most prevalent oral potentially malignant lesion, nevertheless, erythroplakya, which is not as common as leukoplakia, shows a higher malignant potential, and when both clinical features occur simultaneously, malignant evolution is almost imminent 18,29.

Furthermore, several other lesions such as lichen planus and actinic cheilitis, which is due to sun exposure and precede lip cancer, are also included on oral potentially malignant disorders group. For being associated to increased risk for malignant evolution, these lesions require adequate diagnosis and clinical follow-up, and, in cases when lesions present high dysplasia degrees, therapeutic intervention is indicated as preventive conduct 18,29. Early diagnosis of oral cancer is mandatory for enhancing affected patients' quality of life and improving cure and five-year survival chances 20. Unfortunately, in most of cases, OSCC cases are diagnosed on advanced stages, when both the disease and treatment are followed by high morbidity, besides reduced chances of cure and five-year survival and high cost 2. Early diagnosing OSCC is challenging due, basically, to two factors; affected patients usually take long times to appear for professional evaluation, most commonly appearing for treatment four to eight months after noticing any alteration on oral mucosa 6,20,26. Another challenging fact is that dentists, who keeps close contact with patients' oral cavity, are not always properly qualified in recognizing possible malignant oral lesions neither oral potentially malignant lesions and adequately conduct a right diagnosis, referring for oncological treatment, or, in oral potentially malignant disorders cases, conduct the patient through adequate clinical follow-up 7,11,27.

Aiming to raise awareness regarding oral cancer among general population, Fernandópolis city (SP, Brazil) public health service, in association to the Camilo Castelo Branco University Dentistry School, released an oral cancer prevention campaign, which in public health dentists practicing clinical activities were trained by an experienced in diagnosing oral cancer professional. Fernandópolis is located in the state of São Paulo, with approximate 65,000 citizens (demographical density = 117.62 pop./ km², with no discrepant differences between gender. While habits such as tobacco and alcohol consumption and chronic solar exposure due to intense agriculture activities, people who lives in Fernandópolis might be considered at huge risk for oral cancer development. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to present the diagnosis rates of lesions in this campaign.

Material and methods

This study is characterized as a cross-sectional study which aimed to evaluate the oral cancer diagnosis rate during an oral cancer prevention campaign performed in May 2014, which the University participation was approved by the Health Secretary of the City Hall. Participants were recruited for the examination via local radio channel and signed informed consent for participating in the study, approved by the Ethics Committee of the Camilo Castelo Branco University.

Sample

Patients who attended for Basic Health Units on the Fernandópolis city (SP, Brazil) on the aforementioned campaign day.

Examiners' calibration

Dentists performing clinical activities for the Fernandópolis public health service were previously trained by an expert in oral cancer diagnosis professional, who instructed public dentists regarding clinical diagnosis, preventive conducts, and the importance of early diagnosis of oral cancer and oral potentially malignant disorders. Moreover, dentists were encouraged to adequately instruct patients to perform oral self-examination.

Initial examination

Initial patients' examination consisted on a free oroscopy performed by dentists who participated of the calibration. This examination aimed to detect lesions in the oral mucosa and to instruct the individuals regarding risk factors for oral cancer occurrence and the importance of self-examination for oral cancer early detection. Visual examination had its validity confirmed by study performed by Alves et al. 3, which in this technique demonstrated great value for preventive oral cancer programs and public health campaigns.

Diagnosis

Patients who presented with malignant or potentially malignant suspicious oral lesions over oral mucosa during the day of the prevention campaign was performed were referred to the Fernandópolis Dental Specialties Center, where they were reevaluated by the professional responsible for the oral pathology service of the center. Therefore, the right diagnosis was obtained for each patient.

Statistical analysis

Data was transferred to electronic tabulation program and variables of interest data were obtained using the program Epi Info version 7.1.5.0, which is proposed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Results

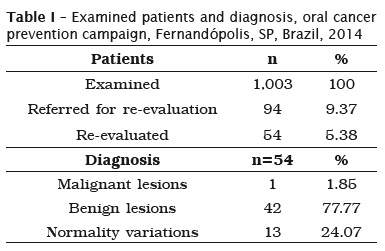

During oral cancer prevention campaign, 16 basic health unities from the city of Fernandópolis worked as headquarters for patients' examination. A total of 1,003 patients were examined by trained dentists searching for oral cancer and oral potentially malignant lesions signs. Among them (n=1,003), 94 (9.37%) were identified with clinically appearing oral lesions and referred for the Dental Specialties Center for re-evaluation and adequate clinical conduct for the right diagnosis by the specialist in oral pathology. Although referred and alerted about the importance of oral cancer early diagnosis, only 54 patients attended for re-evaluation (table I).

From the re-evaluated patients, only 1 (1.85%) was diagnosed with OSCC, whereas most of the patients were diagnosed with oral benign lesions and normal variations (Table 1). When considering the total of 1,003 examined patients during the campaign, oral cancer diagnosis rate was 0.09%, whereas the diagnosis rate for oral benign lesions was 4.18% and for oral normal variations the diagnosis rate was 1.29%.

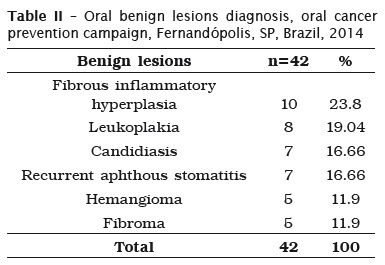

Table II summarizes the oral benign lesions diagnosis frequency during oral cancer prevention campaign performed in Fernandópolis, SP, Brazil, 2014. Among the total of oral benign lesions diagnosed (n=42), the most prevalent was fibrous inflammatory hyperplasia, followed by leukoplakia, candidiasis, and recurrent cold sore ulceration. Hemangioma and fibroma were less frequent among benign lesions (table II). Among leukoplakia lesions diagnosed, no one showed any degree of dysplasia.

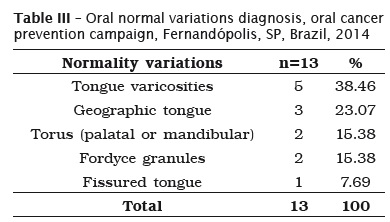

Among oral normal variations diagnosed during oral cancer prevention campaign (n=13), tongue varicosities stood out as the most prevalent, as described in table III.

Discussion

Early diagnosis of oral cancer is mandatory for improving affected patients' quality of life, besides reducing morbidity which follows not only the disease but also the treatment, reduce costs, and increases the chances of cure and survival for these patients 2,20. Nevertheless, in most of cases, oral cancer is diagnosed on advanced stages, and, for this reason, oral cancer represents a public health problem worldwide, requiring attitudes aiming to raise awareness regarding the importance of early diagnosing and preventing this disease among general population and oral health caregivers, since, apparently oral cancer is preventable, being, nowadays, clearly associated to harmful habits such as abusive tobacco smoking and alcohol drinking 2,17,28.

Oral cancer prevention campaign performed in the city of Fernandópolis, Brazil, aimed to examine a great amount of patients to early detect OSCC and oral potentially malignant lesions. Furthermore, this campaign aimed to educate population regarding the importance of preventing and early diagnosing oral cancer. OSCC is a potentially preventable malignant disease, being associated to harmful habits, which, if avoided, OSCC development chances might decrease 17,28 therefore, the importance of performing campaigns like this is to disseminate information regarding oral cancer among general population, once knowing the disease and etiologic factors associated to oral cancer, as much as the importance of early detecting this disease, preventive work becomes easier and more effective 24,26.

During the campaign, only 1 (0.09%), of the total of examined patients (1.003), was diagnosed with oral cancer (OSCC); this low rate of OSCC diagnosis during the campaign might be attributed to two factors; Nemoto et al. 17, attributed the low diagnosis rate of oral cancer during oral cancer preventing campaigns to the fact that campaigns like this does not reach patients at risk for oral cancer development, and commented although campaigns are well structured and reaches a large number of people, other forms of prevention should be developed in order to reach the real risk group for this disease. Nevertheless, further groups over the world have performed oral cancer prevention campaigns with different methodologies, using media resources, however, in the study published by Saleh et al. 23, authors reported results of an oral cancer prevention campaign by mass media approach did not appear to improve the ability of respondents to recognize the signs of oral cancer or retain the information obtained from media, and commented campaign strategies needs to be re-assessed for comprehension, acceptability and potential effectiveness. On the other hand, Martins et al. 16, reported data of 9 years of oral cancer prevention by clinical screening and population education which shows these campaigns were effective and reached benefits for the oral health of elderly population, showing a reduction on the rate of oral cancer diagnosis among each 100,000 patients examined from 20.89 to 11.12. Based on the information that OSCC is one of the most commons types of cancer, the extremely low rate of OSCC found in our study suggests, agreeing with Nemoto et al. 17, this campaign did not reach patients at real risk for the development of this disease, therefore, the need for review on campaign methodologies is clear, especially regarding campaign dissemination.

Another factor which might be attributed to the low oral cancer detection rate during the campaign is a lack regarding dentists' capacity to clinically recognize OSCC lesions, and differentiate from benign lesions and normal variations, once, benign lesions diagnosis and oral normality variations diagnosis rates were wider when compared to oral cancer diagnosis rate. Several studies have been performed aiming to evaluate the capacity of dentists to detect oral cancer and educate general population about the risk factors for oral cancer development and the importance of oral self-examination and early diagnosis of oral cancer, and although in some studies dentists have demonstrated satisfactory knowledge regarding oral cancer, some lacks on this knowledge have been reported 4,27 and furthermore, there is a general agreement regarding the need for continued education programs for these professionals aiming to improve their capacities on adequately diagnosing and preventing oral cancer 10,27,28.

According to Lombardo et al. 13, one factor which results on oral cancer delayed diagnosis is the need for co-responsibility for health by the general population. In other words, general population lacks awareness regarding the importance of early detecting oral cancer, therefore, affected patients only appears for professional evaluation with the lesion on an advanced stage 26. Agrawal et al. 1 reported the unsatisfactory awareness of the general public regarding oral cancer, and commented the need for further dissemination of information on this issue and its associated risk factors. Our results corroborate with these studies, once only 54 of the 94 patients referred for re-evaluation attended for the Fernandópolis Dental Specialties Center. Furthermore, Martins-Filho et al. 15, commented although the fight against oral cancer in Brazil is almost secular, there is still a lot to be done to combat this disease, especially in the field of primary prevention, stressing the importance regarding works around this disease and the need for more competent attitudes for preventing oral cancer.

Among benign lesions diagnosed during the campaign (n=42), 8 (19.04%) were oral leukoplakia. This lesion is considered by the WHO as a potentially malignant lesion by showing a higher prevalence of malignant transformation when compared with other benign lesions and to normal mucosa 18. Malignant transformation rates for leukoplakia lesions are variable, depending on the sample selection and the follow-up time; Lončar-Brzak et al. 14, have reported among 139 leukoplakia lesions, malignant evolution rate on a 10-year follow-up period was 0.64%. More recently, Brouns et al. 5 reported a malignant transformation rate for leukoplakia lesions of approximately 2.6% among 144 lesions studied on a 51-month follow-up period. Although leukoplakia malignant transformation rates are apparently lower when compared to erythroplakya lesions malignant potential 29 the risk for malignant evolution is clear, therefore, patients diagnosed with leukoplakia lesions during this campaign will have adequate clinical followup, and, if necessary, therapeutic approach will be performed.

Conclusion

Oral cancer prevention campaigns might be important for early oral cancer diagnosis and rising awareness among general population regarding oral cancer prevention and the importance of early detecting oral cancer lesions. Nevertheless, the methodologies of these campaigns require improvements aiming to reach population at highrisk for oral cancer development and to train the dentists adequately for clinically detection of oral cancer lesions and education of the patients. Therefore, low oral cancer diagnosis rate does not suggest oral cancer is not a common malignant lesion.

References

1. Agrawal M, Pandey S, Jain S, Maitin S. Oral cancer awareness of the general public in Gorakhpur City, India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(10):5195-9. [ Links ]

2. Akbulut N, Oztas B, Kursun S, Evirgen S. Delayed diagnosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma: a case series. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5(1):291-4.

3. Alves JC, da Silva RP, Cortellazzi KL, de Lima Vazquez F, de Amorim Marques RA, Pereira AC et al. Oral cancer calibration and diagnosis among professionals from the public health in São Paulo, Brazil. Stomatologija. 2013;15(3):78-83.

4. Andrade SN, Muniz LV, Soares JMA, Chaves ALF, Ribeiro RIMDA. Câncer de boca: avaliação do conhecimento e conduta dos dentistas na atenção primária à saúde. Rev Bras Odontol. 2014;71(1):42-7.

5. Brouns EREA, Baart JA, Karagozoglu KH, Aartman IHA, Bloemena E, Waal I. Malignant transformation of oral leukoplakia in a well-defined cohort of 144 patients. Oral Dis. 2014;20(3): 19-24.

6. Chi AC. Patologia epitelial. In: Neville BW, Damm DD, Allem CM, Bouquot JE (Eds). Patologia oral e maxilofacial. 3. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier; 2009. p. 363-453.

7. Falcão MML, Alves TDB, Freitas VS, Coelho TCB. Conhecimento dos cirurgiões-dentistas em relação ao câncer bucal. RGO Rev Gaúcha Odontol. 2010;58(1):27-33.

8. Hashibe M, Brennan P, Chuang SC, Boccia S, Castellsague X, Chen C et al. Interaction between tobacco and alcohol use and the risk of head and neck cancer: pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(2):541-50.

9. Instituto Nacional de Câncer José Alencar Gomes da Silva – INCA. Coordenação Geral de Ações Estratégicas, Coordenação de Prevenção e Vigilância. Estimativa 2014. Incidência de câncer no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Inca; 2014.

10. Ismail AI, Jedele JM, Lim S, Tellez M. A marketing campaign to promote screening for oral cancer. J Am Dental Assoc. 2012;143(9):57-66.

11. Jaber MA. Dental practitioner's knowledge, opinions and methods of management of oral premalignancy and malignancy. Saudi Dent J. 2011;23(1):29-36.

12. Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2001;61(2):69-90.

13. Lombardo EM, Cunha AR, Carrard VC, Bavaresco CS. Atrasos nos encaminhamentos de pacientes com câncer bucal: avaliação qualitativa da percepção dos cirurgiões-dentistas. Ciênc Saúde Col. 2014;19(4):1233-2.

14. Lončar Brzak B, Mravak-Stipetić M, Canjuga I, Baričević M, Baličević D, Sikora M et al. The frequency and malignant transformation rate of oral lichen planus and leukoplakia – a retrospective study. Coll Antropol. 2012;36(3):773-7.

15. Martins Filho, PRS, Santos TDS, Silva LCFD, Piva MR. Oral cancer in Brazil: a secular history of Public Health Policies. RGO Rev Gaúcha Odont. 2014;62(2):159-64.

16. Martins JS, Abreu SCC, Araújo ME, Bourget MMM, Campos FL, Grigoletto MVD et al. Estratégias e resultados da prevenção do câncer bucal em idosos de São Paulo, Brasil, 2001 a 2009. Rev Panam Salud Pub. 2012;31(3):246-52.

17. Nemoto RP, Victorino AA, Pessoa GB, Cunha LLG, Silva JAR, Kanda JL et al. Oral cancer preventive campaigns: are we reaching the real target? Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;81(1): 44-9.

18. Neville BW, Day TA. Oral cancer and precancerous lesions. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;52(4):195-215.

19. Oliveira Ribeiro A, Silva LCF, Martins-Filho PRS. Prevalence of and risk factors for actinic cheilitis in Brazilian fishermen and women. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(11):1370-6.

20. Panzarella V, Pizzo G, Calvino F, Compilato D, Colella G, Campisi G. Diagnostic delay in oral squamous cell carcinoma: the role of cognitive and psychological variables. Int J Oral Sci. 2014;6(1):39-45.

21. Pires FR, Ramos AB, Oliveira JBCD, Tavares AS, Luz PSRD, Santos TCRBD. Oral squamous cell carcinoma: clinicopathological features from 346 cases from a single oral pathology service during an 8-year period. J Appl Oral Sci. 2013;21(5): 460-7.

22. Rana M, Zapf A, Kuehle M, Gellrich NC, Eckardt AM. Clinical evaluation of an autofluorescence diagnostic device for oral cancer detection: a prospective randomized diagnostic study. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2012;21(5):460-6.

23. Saleh A, Yang YH, Ghani WMNWA, Abdullah N, Doss JG, Navonil R et al. Promoting oral cancer awareness and early detection using a mass media approach. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(4):1217-24.

24. Sassi LM, Patussi C, Ramos GHA, Bixofis RB, Schussel JL, Guebur MI. Prevalence of oral lesions in elderly patients on oral cancer prevention campaigns in Parana state Brazil 1989-2013. Braz Dent Sci. 2014;17(3):26-30.

25. Silverman S, Eversole LR, Truelove EL. Essentials of oral medicine. 2. ed. Ontario: B.C. Decker; 2002.

26. Tibaldi ACB, Tomo S, Boer NP, Simonato LE. Avaliação do conhecimento da população do município de Fernandópolis (SP) em relação ao câncer bucal. Arch Health Inv. 2015;4(1):6-12.

27. Tomo S, Mainardi EC, Boer NP, Simonato LE. Conhecimento dos cirurgiões-dentistas em relação ao câncer de boca. Revista Arq Ciências Saúde. 2015;22(2):46-50.

28. Van der Waal I. Are we able to reduce the mortality and morbidity of oral cancer; some considerations. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2013;18(1):33-7.

29. Van der Waal I. Oral potentially malignant disorders: Is malignant transformation predictable and preventable? Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2014;19(4):386-90.

Corresponding author:

Corresponding author:

Saygo Tomo Centro de Oncologia Bucal

Faculdade de Odontologia de Araçatuba

Universidade Estadual Paulista Júlio de Mesquita Filho

Rua José Bonifácio, n. 1.193

CEP 16015-050

Araçatuba – SP – Brasil

E-mail: saygo.18@hotmail.com

Received for publication: November 8, 2015

Accepted for publication: March 24, 2016