Services on Demand

Article

Related links

Share

RSBO (Online)

On-line version ISSN 1984-5685

RSBO (Online) vol.14 n.1 Joinville Jan./Mar. 2017

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE

Beliefs in relation to elderly between Dentistry undergraduates of private university of Parana

Herbert Rubens Koch-Filho I; Luis Fernando Beiger II; Matheus Augusto Mendes II

I Department of Dentistry, Pontifical Catholic University of Parana – Curitiba – PR – Brazil

II Private Practice – Curitiba – PR – Brazil

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Aging is a sociocultural concept characterized by the opposite to the youth. Generalization and the lack of knowledge about this stage of life can lead to false assessments that tend to oscillate between positive and negative. Objective: a) To characterize the beliefs about aging of Dentistry undergraduates from a private higher education institution; b) to verify if the belief of the undergraduates had about aging may interfere in the choice of future dental care given to older people, and; c) to assess the profile of the respondents by gender, age and graduation period. Material and methods: This cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted with students properly enrolled in the Dentistry course of a private institution, in 2016 (N = 90). The profile of the population was defined by gender, age and graduation period. It was verified the preference and predilection in future working or not working with a certain age group. Also, the beliefs about aging were investigated through a semantic scale. Distributions of absolute and relative frequencies were made. Statistical analysis was given by using SPSS version 20.0. Results: Most respondents were female (78.9%); with a mean age of 23.34 years; enrolled in the 8th period; 51.1% said they had no preference in future work with particular age range; and, there was a predominance of positive view, with tendencies towards neutrality. There were no statistically significant differences between the beliefs toward aging and the variables: gender, age and period. Statistically significant dependencies were found between the beliefs about old age and preference in working or not working in future treat a certain age range of the population. Conclusion: The respondents have a more positive view of old age; no predilection to provide dental care to a certain age group, highlighting a general and humanist profile in relation to chronological age.

Keywords: beliefs; old age; Gerontology.

Introduction

Aging is a concept historically constructed, socio-culturally determined and characterized by being the opposite to youth 2,7. The attitudes towards aging incorporate a conceptual field which includes beliefs, prejudices and stereotypes, and these maintain a reciprocal relationship with the scientific and social context they are 2,7,27,28. Therefore, these are socially learned behavioral predispositions 10,32. On the other hand, the beliefs comprise a knowledge structure shared with others and enable individuals to organize, assess and prioritize the information received by interfering on the design about the world and about his/herself 7,28. So, attitudes and beliefs can function as regulators of the behavior of individuals and groups 7,27,28 and may determine social practices and policies regarding the elderly 7.

In all contexts, the overgeneralization induces the superstitions which tend to oscillate between "the glorification" and "the depreciation", between "acceptance" and "rejection", as well as between the "realism and idealism" of old age and the figure of the elderly 7,27. From this point of view, the lack of knowledge about aging and old age leads to false assessments that translate into prejudice, both negatives as positives 28.

Assuming that the University environment as a forming, transforming and stimulating agent of knowledge that can break down prejudices 8, this study aimed to: a) characterize the beliefs in relation to old age among Dentistry undergraduates from a private higher education institution (HEI), located in the city of Curitiba (PR, Brazil); b) to verify if the belief of the undergraduates had about aging may interfere in the choice of future dental care given to older people; c) to assess the profile of the respondents by gender, age and graduation period.

Material and methods

This cross-sectional and descriptive study was obtained with undergraduates at the of 8th and 9th periods during the course of Dentistry at the Pontifical Catholic University of Parana (PUCPR). We verified all students enrolled in these periods in 2016, except for the undergraduates at the 9th period, totaling 90 students.

This study was submitted and approved to the Institutional Review Board. The participants were informed about the nature of the study, its objectives and method of development. Also, they were previously instructed about the risks and benefits, the right to confidentiality and the optional character of participation. Individuals who agreed in participating in the study signed an informed consent, whose copy was available to the participants.

All data were obtained through the application of the instruments by two examiners instructed and trained. The participants were interviewed as described by Leão and Oliveira 19, in which the person responds to questions in the presence of the interviewer, allowing that all questionnaires were fully completed. The interviews took place at the site where the subjects develop their academic routine activities, without the need of a special place.

The profile of the studied population was defined through the dichotomous variables sex, age and period of the course. The variable gender has two possibilities: male and female; as well as the period: 8th and 9th. For the variable age, the threshold was the chronological age between 19 and 29 years for youths (group 1); 30 to 44 years for young adults (group 2).

To verified the intention and non-intention to further work with a given age range, we applied a questionnaire with two questions in a seven-point polytomic nominal scale; the first question referred to which age group the undergraduates will prefer working in their professional life; the second question inquired about which age group they will have no preference. The age strata were composed according to: a) Statute of the child and adolescent 3: child <12 years; adolescent >/=12<19 years; b) young – Statute of the Youth 5: young >/=19<30 years; c) the division between the adults was performed as the age strata in the Synthesis of Social Indicators 2015 15, such as 30-34, 35-39 and 40-44 considered as young adults and 45-49, 50-54 and 55-59 mature adult; d) the age range cut for the elderly was based on the Statute of the Elderly 4: elderly >/= 60 years.

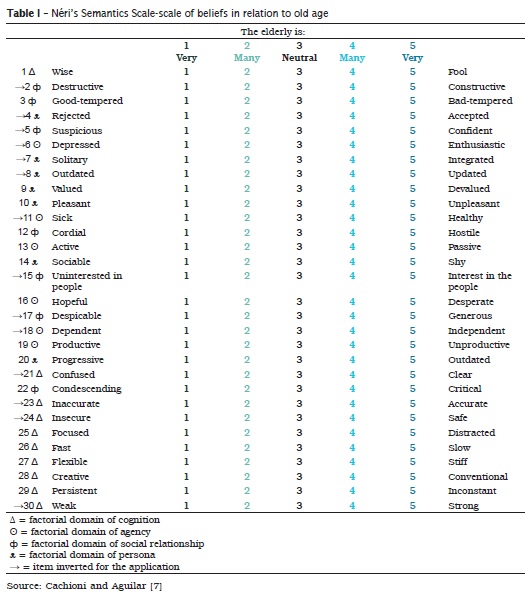

To evaluate the beliefs about old age, we used an instrument constructed by Neri 24,25 named Belief Scale in relation to old age (Neri's semantics scale), validated by Cachioni 6. This tool consists of 30 items that counteracts two commonly used adjectives as social labels to describe and/or discriminate against older people. The variables were arranged in a factorial structure that associates old age: {a} to cognition or the ability to process information and to solve problems, with reflections on social adjustment (10 items); {b} to agency capacity, i.e. autonomy and instrumentality for the accomplishment of tasks (6 items); {c} to the social relationship, the affective-motivational aspects, reflected in the social interaction of the elderly (7 items); {d} the social image (persona), which can lead to social labels, commonly used to designate and discriminate against elderly (7 items). According to table I.

The intensity of the responses was indicated by a five-point scale according to the relative position to each pair of positive and negative adjectives or the trend of invalidity. Thus, the answers may have five orders: a) value one (1)-extremely positive; b) value two (2)-positive; c) value three (3) -neutral; d) value four (4) -negative; and e) value five (5) -extremely negative. Questions 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 11, 15, 17, 18, 21, 23, 24, and 30 had the numeric values of the scores reversed in the application. Thus, one can establish a score in relation to the total sum possible (continuous) for the scale according to the scores: a) very positive vision, between 30 and 59; b) positive view, between 60 and 89; c) total neutrality, value 90; d) negative view, between 91 and 120; and, e) very negative vision, between 121 and 150. Similarly, the cognition factor, according to the continuous scores, will be assessed as: a)10-19, very positive); b) 20-29, positive; c) 30, total neutrality; d) 31-40, negative; and 41-50, very negative. Equally, a continuous score was adopted for the factor agency: a)6-11, extremely positive); b) 12-17, positive; c) 18, total neutrality; d) 19-24, negative; e) 25-30, extremely negative. Still, solid scores were adopted for the social relationship factors and persona: a)7-13, extremely positive); b) 14-19, positive; c) 21, total neutrality; d) 22-28, negative; e) 29-35, very negative). Once achieved the continuous, the value of the weighted average was adopted which was obtained through the value found (X) divided by the maximum possible value in the scale (total score = 150; cognition = 50; agency = 30; social relationship and persona = 35) multiplied by 5.

A database was built using the data tabulation in Microsoft Office Excel 2013. The primary data were analyzed through the distribution of absolute and relative frequencies. The statistical analyses were carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software (IBM SPSS Statistics) version 20.0. The variables age, period, gender was considered in the continuous and dichotomized way. The variables predilection and non-predilection to work with particular age group were studied in the continuous and ordinal way. The belief in relation to old age was exposed by the average weighted and evaluated in continuous and ordinal way.

The continuous variable belief in relation to old age was compared with continuous variables, gender and age. For this purpose, we used the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test for two independent samples. To verify which factors of Neri's semantics scale more contributed to the belief in relation to old age, we used Pearson's correlation coefficient. To check the dependency between the continuous variable belief in relation to old age and the predilection and no predilection to treat a particular age group, considering that the variables were arranged by a Nominal Polytomic Scale, we applied Chi-square test.

Results

Most of the respondents were female (78.9%). The average age was of 23.34 years, ranging from 20 to 43 years. Forty-eight people were enrolled in the 8th period (53.3%), while 42 at the 9th period (46.7%).

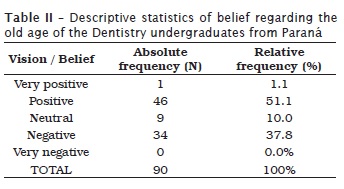

Most of the respondents (51.1%) reported they did not have preference in working with a particular group of people. Only 6.6% (n = 6) reported to prefer working with the age extremes: children (n=4;4.4%) and elderly (n=2;2.2%). When asked about to the age group who they would like to work, 34.4% (n = 31) indicated the children (0-11 years) and 13.3% (n = 12) the elderly (60 years of age or older). About the belief in relation to old age, there was a predominance of positive view (51.1%), as shown in table II.

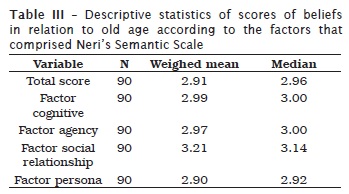

The weighted average of the total score of Neri's semantics scale (beliefs in relation to old age) and cognitive factors, agency, social relationship, and persona is expressed in table III.

The weighted average (2.91) and the median (2.96) of the total scores indicated that respondents have a little more positive vision about old age. However, the variable social relationship (weighted average = 3.21) presented a more negative view.

The weighed mean of each one of the 30 available items showed that the respondents perceived the oldness more positively in relation to the following elderly characteristics: a) wise (2.17); b) constructive (2.58); good-tempered (2.83); c) pleasant (2.40); d) cordiality (2.49); e) active (2.96); f) sociable (2.49); g) interested for the people (2.46); h) hopeful (2.59); i) generous (2.38); j) productive (2.79); k) accurate (2.96); l) safeness (2.88); m) persistent (2.53). A more negative view prevailed for the following elderly characteristics: a) rejected (3.4); b) suspicious (3.21); c) depressed (3.4); d) isolates (3.18); e) outdated (3.03); f) devalued (3.22); g) sick (3.22); h) dependent (3.28); I) confused (3.2); j) critics (3.51); k) distracted (3.18); l) slow (3.67); m) inflexible (3.30); n) conventional (3.23); o) weak (3.02). The average of the answers that matched with the value of nullity (3.0) was observed only in item 20, in which the quality of the elderly was opposed in advanced X outdated.

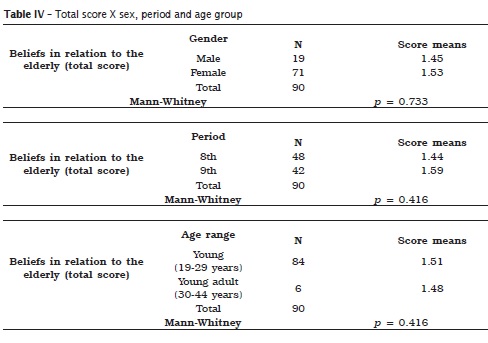

Concerning to the comparison of the weighted average of the variable beliefs in relation to old age and the variables sex, age and period, the Mann-Whitney test showed that there were no statistically significant differences between variables (p > 0.05) (table IV).

In relation to the factor that most collaborated in the formation of the total score of the beliefs in relation to old age, the Pearson coefficient of correlation showed that persona presented weak positive correlation of 0.252, but statistically significant (p = 0.016), with the greatest contribution. Other factors did not show statistically significant correlation, because assumed value of p > 0.05 [cognition (-0.114/p = 0.28); Agency (-0.50/p = 0.63); social relationship (-0.23/p = 0.128)].

Crossing the variables beliefs in relation to the oldness with the variable preference for treating one definitive age range (p = 0.97) and the preference for not taking care of one definitive age range (p = 0.93), the test of Qui-Square showed no statistical dependence (p > 0.05).

Discussion

The study population was mainly young females. These characteristics are observed in studies on Brazilian Dentistry undergraduates 1,12,20,21,23,30. Although mostly females are attending the Dentistry School, nowadays, this phenomenon is recent and Dentistry was considered a male profession at the past 12.

The results of this study arose from the personal experience of the respondents, because they did not attend any formal discipline of Gerontology. A study conducted with public undergraduates of Coimbra (Portugal) showed that those who have attended courses in the area of health and who had theoretical and practical courses on aging showed tto know more about the physical, psychological and social aspects of old age 10. The studies of Malliarakis and Heine 22, Neri and Jorge 28 and Schaffer and Biasus 33 also highlight the importance of formal contents of Gerontology for student and professional training. In this sense, it is necessary to emphasize that the lack of scientific knowledge among health professionals may represent a barrier for the transformation of attitudes and clarification on the characteristics and potential of aging 7,8,28.

This research showed that there is no predilection for treating a particular age in the future. This finding highlighted the human and generalist value of the studied population, which meets the Brazilian curriculum guidelines for Dentistry courses: the formation of generalist professionals with solid humanistic and ethical training, guided to the health promotion 9. Also, the outcomes showed that the respondents are not subject to sanitary Gerontophobia, cited by Rovira 31 as the aversion to the elderly in the field of health, whose basis is supported on belief in negative stereotypes such as "the investment in the health of the elderly have no social return" and "represents a threat to the financial sustainability of the health systems".

The social mark of old age is to be in opposition to the youth. This causes recurrent oscillation between a social vision of either idealization and depreciation of the elderly 10,14. However, Zanon et al. 34 emphasize that there is not a single response with regard to aging, because this is a heterogeneous process realized and analyzed by plural and multidimensional visions. Although the numeric values expressed in this research pointed out to a little more positive vision, there was a trend towards neutrality with respect to antagonistic positive and negative adjectives. This fact revealed that respondents interpret old age as a phase of life characterized by heterogeneity. Similar results, in different populations, were found in other study 7,13,28,32,34.

The results observed for the domains of the Neri's Semantics Scale revealed that the cognitive value balances the adjectives "wise" and "fool" was the most cited as a positive belief. It should be stressed that, in considering that all elderly people are wise, the respondent had a type of positive prejudice of the elderly that often consists of static knowledge of the past and not with the ability to deal with contemporary challenges 7,26. The overestimation of positive attributes as wisdom may induce false beliefs and create expectations of competence that can lead to frustrations 11,17,18,26,29. The item with most negative view also referred to a cognitive domain, which contrasts the adjectives "fast" and "slow". In this sense, it must be considered that, although the elderly consists of an age group with distinct physical, psychological and social characteristics, some losses as the speed is common to senescence, i.e. something common to aging 16,33. However, one must be careful not to generalize in associating greater slowness with disability. The most positive belief to wisdom and the most negative believe to slowness was also reported in the study of Fernandez and Ruiz 13.

Thus, it is necessary to recognize that aging is a complex and multifaceted process and the limited, inflexible to uncritical, knowledge tends to the formation of stereotypes 17. Therefore, as highlighted by Zanon et al. 34, it is necessary to work the gerontological education in educational spaces, health centers and associations to get the promotion of social benefits that can be translated into understanding, respect, affection and quality of life.

However, it must be considered this study's limitations: cross-sectional study on a single Dentistry School of an educational institution that does not provide the discipline of Gerontology in the formal curriculum and a population restricted to the undergraduates of the last year. Therefore, we cannot make inferences for the large number of Brazilian Dentistry undergraduates.

Conclusion

a) This study is the first Brazilian study involving the beliefs in relation to old age among Brazilian Dentistry undergraduates;

b) the respondents had a positive vision of old age, but with a tendency towards neutrality, which may lead to the assumption of heterogeneity;

c) the study population did not have a predilection in providing dental treatment for a particular dental age, emphasizing a generalist and humanist profile with regard to chronological age;

d) the variables sex, age, period and predilection or non-predilection in treating a given age group were not statistically related to the beliefs in relation to old age.

It is believed that this study can collaborate to further analyses and discussions about gerontological education in University spaces. Further studies on the subject are necessary.

References

1. Araújo DB, Campos EJ, Martins GB, Lima MJP, Araújo MTB. Perfil dos acadêmicos concluintes dos cursos de Odontologia em 2014 no estado da Bahia. Rev Ciênc Méd Biol. 2015;14(2):198-205. [ Links ]

2. Bissoli PGM, Cachioni M. Educação gerontológica: breve intervenção em centro de convivência-dia e seus impactos nos profissionais. Revista Kairós Gerontologia 2011;14(4):143-64.

3. Brasil. Estatuto da Criança e do Adolescente. 3. ed. Brasília: Câmara dos Deputados; 2001. 92 p.

4. Brasil. Estatuto da Juventude. Brasília: Câmara dos Deputados; 2013. 37 p.

5. Brasil. Estatuto do Idoso. Brasília: Senado Federal; 2003. 66 p.

6. Cachioni M. Quem educa os idosos? Um estudo sobre professores de Universidades da Terceira Idade. Campinas: Átomo Alínea; 2003. 258 p.

7. Cachioni M, Aguilar LE. Crenças em relação à velhice entre alunos de graduação, funcionários e coordenadores-professores envolvidos com as demandas da velhice em universidades brasileiras. Revista Kairós. 2008; 11(2):95-119.

8. Cachioni M, Néri AL. Educação e gerontologia: desafios e oportunidades. Revista Brasileira de Ciências do Envelhecimento Humano. 2004;1(1):99-115.

9. Conselho Nacional de Educação – CNE. Câmara de Educação Superior. Resolução CNE/CES 3, de 19 de fevereiro de 2002. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília; 2002. 10 p.

10. Cordeiro MPAA, Vicente F. Atitudes e conhecimentos dos estudantes do ensino superior público de Coimbra face à velhice: influência de experiências de vida e académicas. International Journal of Developmental and Education Psychology. 2010;1:299-305.

11. Costa MES. Aspectos biopsicossociais da velhice. In: Costa MES. Gerontodrama: a velhice em cena: estudos clínicos e psicodramáticos sobre o envelhecimento e a terceira idade. São Paulo: Agora; 1998. p. 39-54.

12. Costa SM, Durães SJA, Abreu MHNG. Feminização do curso de Odontologia da Universidade Estadual Montes Claros. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. 2010;15(Supl.1):1865-73.

13. Ferreira VM, Ruiz T. Atitudes e conhecimentos de agentes comunitários de saúde e suas relações com idosos. Rev Saúde Pública. 2012;46(5):843-9.

14. Goldani AM. Desafios do "preconceito etário" no Brasil. Educ Soc. 2010;31(111):411-34.

15. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística – IBGE. Síntese de indicadores sociais: uma análise das condições de vida da população brasileira. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2015. 137 p.

16. Koch-Filho HR, Bisinelli JC. Abordagem de famílias com idosos. In: Moysés ST, Kriger L, Moysés SJ. (Eds.). Saúde bucal das famílias: trabalhando com evidências. São Paulo: Artes Médicas; 2008. p. 236-45.

17. Koch-Filho HRK, Koch LFA, Koch HR, Koch MFN, Diniewicz FA, Diniz RA. Envelhecimento humano e ancianismo: revisão. Rev Clín Pesq Odontol. 2010;6(2):155-60.

18. Koch-Filho HRK, Koch LFA, Kusma SM, Werneck RI, Bisinelli JC, Moysés ST et al. Uma reflexão sobre o preconceito etário na saúde. Revista Gestão & Saúde. 2012;4(2):40-8.

19. Leão AT, Oliveira BH. Questionários na pesquisa odontológica. In: Luiz RR, Costa AJL, Nadanovsky P. Epidemiologia e bioestatística na pesquisa odontológica. São Paulo: Atheneu; 2005. p. 273-90.

20. Leite DFBM, Trigueiro M, Martins IMCLB, Lima-Neto TJ, Santos MQ. Perfil socioeconômico de 253 graduandos de Odontologia de uma instituição privada em João Pessoa – PB em 2011. J Health Sci Inst. 2012;30(2):117-9.

21. Loffredo LCM, Pinelli C, Garcia PPNS, Scaf G, Camparis CM. Característica socioeconômica, cultural e familiar de estudantes de Odontologia. Revista de Odontologia da UNESP. 2004;33(4):175-82.

22. Malliarakis DR, Heine C. Is gerontological nursing included in baccataureate nursing programs? Gerontol Nurs. 1990;16(6):4-7.

23. Moysés SJ. Políticas de saúde e formação de recursos humanos em Odontologia. Rev ABENO. 2004;4(1):30-7.

24. Néri AL. Envelhecer num país de jovens: significados de velho e velhice segundo brasileiros não idosos. Campinas: Unicamp; 1991.

25. Néri AL. Atitudes e crenças em relação à velhice: o que pensa o pessoal do Senac – São Paulo. Relatório Técnico. São Paulo: Senac; 1995.

26. Néri AL. Atitudes e preconceitos em relação à velhice. In: Fundação Perseu Abramo - FPA. Idosos no Brasil: vivências, desafios e expectativas na terceira idade. São Paulo: Fundação Perseu Abramo; 2007. p. 33-46.

27. Néri AL. Atitudes em relação à velhice. In: Néri AL (Ed.). Palavras-chave em gerontologia. 3. ed. Campinas: Alínea; 2008. p. 13-5.

28. Néri AA, Jorge MD. Atitudes e conhecimentos em relação à velhice em estudantes de graduação em educação e em saúde: subsídios ao planejamento curricular. Estudos de Psicologia. 2006;23(2):127-37.

29. Palmore E. The ageism survey: first findings. The Gerontologist. 2001;41(5):572-5.

30. Pinheiro VC, Menezes LMB, Aguiar ASW, Moura WVB, Almeida MEL, Pinheiro FMC. Inserção dos egressos do curso de Odontologia no mercado de trabalho. RGO. 2011;59(2):277-83.

31. Rovira ER. Salud y personas mayores: la discriminación sanitária del mayor. Santander: Cantabria Académica; 2004. 68 p.

32. Santos BF, Ordonez TN, Silva TBL, Cachioni M. Identificação das crenças em relação à velhice e ganhos percebidos de professores do CIEJA. Revista Kairós Gerontologia. 2011;14(2):119-41.

33. Schaffer KC, Biasus F. Representações sociais do envelhecimento, cuidado e saúde do idoso para estudantes e profissionais de enfermagem. RBCEH. 2012;9(3):356-70.

34. Zanon CBFM, Alves VP, Cardenas CJ. Como vai a educação gerontológica nas escolas públicas do Distrito Federal? Um estudo com idosos e jovens. Rev Bras Geriatr Gerontol. 2011;14(3):555-66.

Corresponding author:

Corresponding author:

Herbert Rubens Koch-Filho

Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná

Campus Universitário Curitiba

Escola de Ciências da Vida

Departamento de Odontologia

Rua Imaculada Conceição, 1155

Prado Velho CEP 80215-901

Curitiba – Paraná – Brasil

E-mail: h.koch@pucpr.br

Received for publication: July 1, 2016

Accepted for publication: November 22, 2016